No Cards Accepted

Editor’s Note: Last month, we asked our readers to select a country for us to focus on and collected the results. Now, we’re pleased to offer our inaugural Readers’ Choice Week, with reports on four of the top vote-getters. We wish we could have featured all the great suggestions – but hope to in 2023. Until then, the DailyChatter team wishes you and your loved ones a healthy and peaceful New Year.

READERS’ CHOICE

No Cards Accepted

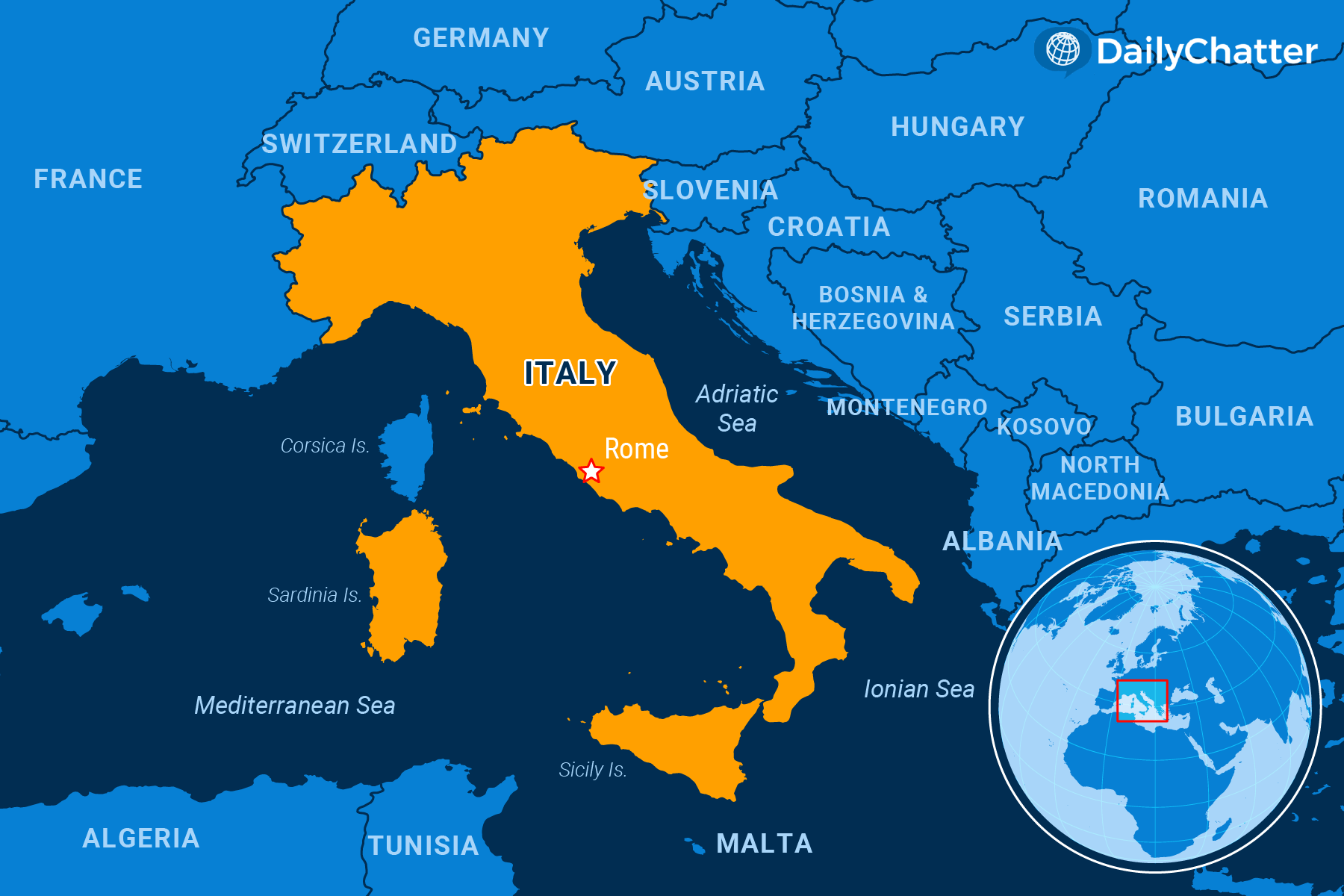

ITALY

Over the last decade, Italian authorities have opened new fronts in the battle against tax cheats, including scouring posh Alpine ski resorts for the owners of Lamborghinis and Maseratis claiming poverty wages on their tax returns. They used special canine units to sniff out bags of cash crossing the border to Switzerland, and gained court orders to search safe deposit boxes suspected of holding illicit jewels.

Tax evasion has long been a problem in Italy, which has a large black market economy – some estimates say it accounts for more than a fourth of the country’s GDP – and that’s part of the reason it is among the world’s most indebted countries.

But when it came to reducing the role of cash in the Italian economy, Italy was ahead of the game. Italy’s first statute on money laundering, indeed the first in Europe, took effect in 1978. Sure, it was aimed at fighting the Mafia’s money-laundering operations, but it also helped limit tough-to-trace cash transactions.

“There was a time when other countries studied Italy’s money-laundering statutes,” Javier Noriega, senior economist with Milan-based investment bankers Hildebrandt and Ferrar told DailyChatter. “Cash had long been king for smaller transactions but it became more difficult to plop down a big box of cash to buy property or a car.”

The laws that started out with a cap of 1,000 euros ($1,061) on cash transactions eventually included the near-elimination of fees for small bank card transactions. Slower than in other European countries, Italians started using credit cards for even the smallest payments. The credit card penetration rate is now expected to surpass 50 percent next year, according to Statista.

“I remember the first time someone pulled out a bank card to pay for a cup of coffee,” Antonino Gattuso, a coffee bar owner in Rome where a cup of espresso costs 1.10 euros, said in an interview. “I thought they were crazy. But it’s become more and more common, especially with young people.”

But the newly installed Italian government, led by nationalist Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni, is taking steps to reverse some of the changes. Earlier this year, lawmakers doubled the cap on cash transactions to 2,000 euros. And last month, the Meloni government raised it again, to 5,000 euros. According to Italian media reports, the original plan had been to raise it to 10,000 euros.

Meloni says there’s little evidence that connects a greater use of cash to tax evasion. Instead, she explains the move back toward cash is designed to boost poor Italians and mom-and-pop businesses that might have less access to digital payment methods.

In fact, Meloni even wanted to include a measure in the country’s 2023 budget to allow vendors to refuse bank cards for purchases under 60 euros. But that move was criticized by European Union officials who set conditions on its grants and loans, Bloomberg noted, due to worries about tax evasion and other financial crimes. Earlier this month, it was removed from the budget bill, Italian news agency ANSA reported.

Italy’s initial fight against money laundering started more than 50 years ago after Italian crime families started growing beyond their traditional businesses of extortion, intimidation, smuggling, and prostitution. Their new ground involved vying for bloated public contracts and forcing their way into real-estate deals, areas that required buying influence among the political class – and that required large amounts of untraceable cash.

“When people talk about fighting the Mafia’s influence they talk about capturing crime bosses and dramatic raids,” said Sergio Nazzaro, an Italian journalist and author specializing in organized crime in an interview. “But (the focus) should be (on) banks and the processes that make it possible for the Mafia to do what it does. That’s where the anti-money laundering rules come in.”

Organized crime has mostly adapted to the changes in the rules over recent decades, and few think the raised cash limits will impact on the mob’s reach. But the reasoning behind the changes is still unclear. According to one analyst, the motives are almost surely political.

Meloni became Italy’s first-ever female prime minister by championing controversial views critical of the euro currency, refugee policies, the EU, and NATO. But since then, she’s moved toward the center, taking mainstream views aimed at sparking economic growth, curbing inflation, and keeping the lights on.

The moves toward cash are simply aimed at appealing to Meloni’s base, a group that might lose patience with the measured, centrist governing style from their long-time firebrand, says Oreste Massari, a political science professor at Rome’s La Sapienza University.

“She has to give something to supporters who complain about big business having a hand in everything,” he told DailyChatter. “Knowing that a multinational bank isn’t involved in their morning coffee bar transaction, it means something.”

— Eric J. Lyman, Rome, Italy, for DailyChatter

Editor’s Note

The World, Briefly and COVID-19 Global Update will return next week.

DISCOVERIES

Survival Skills

Housework and cooking don’t come easy to Japanese men. Most have never learned.

That’s because strict gender roles in domestic affairs have persisted in Japan: The wife usually takes care of meal preparation and cleaning, while the husband supports the family financially.

That labor division has persisted even though a majority of women now work outside the home.

According to a survey by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Japanese men spend an average of 40 minutes a day on household responsibilities and child care, a fifth of the time spent by their wives, and the lowest proportion among rich countries. Only 14 percent said they cooked for themselves on a regular basis.

Still, when men retire and would like to help out more at home, or are forced to because of a new-found single status due to divorce or the death of a spouse, or because their wives are fed up, there is one problem: Men don’t know how to cook or clean.

Enter cooking and home economics classes for older men, which are becoming increasingly popular in Japan.

Masahiro Yoshida, a retired government administrator, is one of a growing number of older Japanese men who have signed up for courses, such as preparing dishes, shopping for meat and cleaning food stains.

“I had no idea how complex the cooking process was,” he told the Washington Post.

Their popularity has also prompted the government to help, with some community centers offering free classes to teach cooking, cleaning, ironing, and how to do the laundry.

For 74-year-old Takeshi Kaneko, the cooking classes have helped him meet more friends and host meals for his adult children following the death of his wife.

“If their mother were alive, she would surely have cooked for them and made them feel at home, so I want to do the same,” Kaneko told the newspaper.

Thank you for reading or listening to DailyChatter. If you’re not already a subscriber, you can become one by going to dailychatter.com/subscribe.