Here, Again

NEED TO KNOW

Here, Again

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

For years, the Rwanda-backed M23 rebels have set their sights on capturing Goma – the strategic hub of a region in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) – that holds trillions of dollars of untapped mineral wealth.

Then last week, in a lightning advance, they did it, with help from thousands of Rwandan soldiers, as resistance from the army, United Nations soldiers, and mercenaries melted away. Now, the rebels are eyeing the entire country even as they declared a ceasefire Tuesday for “humanitarian” reasons.

“We want to go to Kinshasa, take power, and lead the country,” said Corneille Nangaa, a leader of the self-described “people’s army” of M23, who is a former Congolese election official in the DRC, and sanctioned by the US for “undermining democracy.”

Offering the leaders of the Congo “a dialogue,” he said the group wants to bring “peace.”

Congo’s defense minister, Guy Kabombo Muadiamvita, scoffed at the offer. “We will stay here in Congo and fight,” he said. “If we do not stay alive here, let’s stay dead here.”

Once again, analysts say, the region is on the edge of a full-blown conflict, one that could engulf the DRC, Rwanda, Uganda, and possibly South Africa and Burundi. Still, they aren’t surprised.

“The warning signs were always there, said Murithi Mutiga of the Crisis Group. “(Rwanda) was adopting very bellicose rhetoric and the Congolese government was also adopting very, very aggressive rhetoric.”

The roots of the conflict date back to the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, in which almost a million Tutsis and Hutu moderates were killed by Hutu extremists. Tutsi rebels, led by current Rwandan President Paul Kagame, stopped the killing and pushed the Hutu perpetrators across the border into the DRC. Now, Kagame says that he wants to protect ethnic Tutsis in Congo and protect his country from the other rebel groups in the DRC.

More than 100 armed groups operate in the country, vying for control of the east which holds vast mineral deposits worth $24 trillion such as lithium, rare earth minerals, and others that are critical to the world’s tech gadgets. One group, known as the FDLR, whose members include alleged perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide, “is fully integrated into” the Congolese military, Kagame said, something the DRC denies.

Still, Kagame has long denied supporting the M23 rebel group. However, the US, the UN, and others say it is actively involved, dreaming of creating a “Greater Rwanda.” The UN says Rwanda uses the group to extract Congo’s minerals.

In August, a ceasefire – now moot – took effect between Congo and Rwanda to end a war that has killed 6 million, mainly through hunger and disease. However, Congo’s president, Felix Tshisekedi, has long rejected talks with M23 as Kagame has wanted.

Instead, the Congolese are furious that the West hasn’t intervened. But Rwanda has outsized clout with the international community because it has long been seen as a model of democratic governance and economic management in the region, a reputation not necessarily deserved over the past few years.

Meanwhile, regional heavyweight South Africa has been drawn into the fray. South African President Cyril Ramaphosa last week blamed Rwanda for the deaths of 13 South African peacekeepers in eastern Congo. Kagame responded that those peacekeepers made up a “belligerent force.” “If South Africa prefers confrontation, Rwanda will deal with the matter in that context any day,” the Rwandan leader said.

Caught in the middle, meanwhile, are millions of Congolese, tired from almost three decades of conflict, tired of being uprooted from their homes and pushed from one refugee camp to another, tired of the carnage.

On the ground, the conditions in Goma are dire, say humanitarian officials. The city remains largely without food, electricity, and water after its capture by the rebels. More than 900 people were killed in last week’s takeover of Goma. Witnesses said bodies lay on the streets and UN officials reported gang rapes and executions.

Goma has served as a center for more than 6 million people displaced by the ongoing conflict in the DRC. About 700,000 people have been displaced again by the new fighting, the UN said.

Now, residents in the eastern city of Bukavu are terrified: The rebels are said to be advancing their way even as Goma’s residents try to cope.

“We have nothing left to eat … my shop has been looted – I curse this war,” Adeline Tuma, who lives in Goma with her four children, told the Guardian. “A new, grim chapter of our lives begins.”

THE WORLD, BRIEFLY

A Shaky Marriage

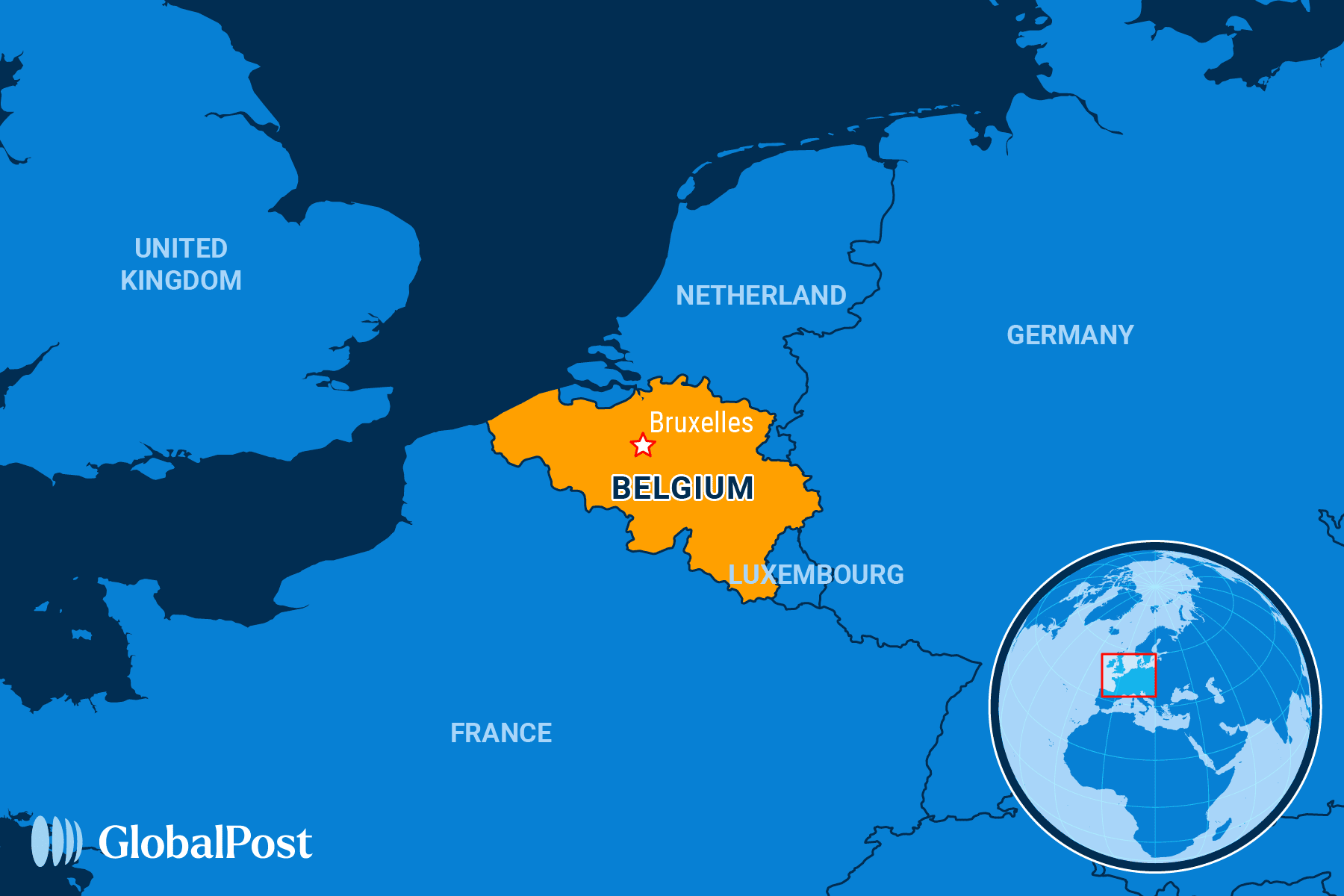

BELGIUM

Flemish nationalist politician Bart De Wever was officially sworn in as Belgium’s new prime minister this week, marking the first time in the country’s history that a separatist figure from the Dutch-speaking Flanders region will hold the top position, the Associated Press reported Tuesday.

De Wever’s swearing-in came after seven months of coalition negotiations following the June federal elections that saw his conservative New Flemish Alliance (N-VA) party gain the most seats, but not a clear majority.

The five-party coalition – comprised of three Flemish parties and two parties from the French-speaking Wallonia region – reached an agreement last week after De Wever had threatened to walk out.

Together, they hold an 81-seat majority in Belgium’s 150-seat parliament, wrote Agence France-Presse.

De Wever’s pick as prime minister surprised many in Belgium, where the conservative leader is known for pushing for Flanders’ independence and thus breaking up the Belgian state. He is remembered for a series of nationalist stunts, such as driving trucks of fake money to Wallonia to protest financial transfers to the region, according to the Belgium-based Brussels Times.

But in recent years, he has softened his stance on separatism and called for “confederalism,” which would grant his Flanders region more powers while keeping the country together.

Observers suggested that his decision to take the role of prime minister and swear allegiance to Belgium’s King Philippe indicated a shift towards working with the system.

The new 15-member cabinet will now focus on a series of austerity policies aimed at addressing Belgium’s budget deficit, which was 4.4 percent of the gross domestic product in 2023 – exceeding the European Union’s three percent limit.

The government also seeks to reduce social benefits and implement pension reforms, sparking opposition from labor unions. De Wever has also called for reducing the EU’s “regulatory fervor” to boost corporate competitiveness and the bloc’s defense should remain anchored within NATO, added Reuters.

The new prime minister and his N-VA party have also called for stricter immigration rules and to scrap Belgium’s planned nuclear energy phase-out, ensuring continued reliance on nuclear power.

Laws and Loopholes

EUROPEAN UNION

The European Union this week moved to ban some “unacceptable” uses of Artificial Intelligence (AI), setting the world’s first limits on the technology, even as critics said the bloc didn’t go far enough, Politico reported.

With the AI Act, the bloc became the first national or supranational entity to attempt to regulate the technology, banning AI’s use to profile future criminals with “predictive policing.” It was one of seven categories the bloc banned as of Feb. 2, including the practice of scraping images from the Internet to build a database for facial recognition.

The AI Act aims to ensure the “trustworthy” use of AI in Europe, the European Commission explained.

The rules set the EU apart from other countries or regions where there are few restrictions on the technology, underscoring its usual role as safeguarding the public from abuse of technology. The bloc has long been at the forefront of Internet privacy rights.

The bloc will create an enforcement authority for AI rules by August. Officials also said they would further define and enhance the rules over the next 18 months.

Italian lawmaker Brando Benifei, who was involved in the legislation, said that the bans are linked “to the protection of our democracies.”

There have been cases of AI run amok that led the EU to consider such restrictions.

For example, in 2019, Dutch tax authorities used an algorithm to spot suspected benefit fraud and ended up wrongly accusing about 26,000 people of fraud. That practice – predictive policing – is banned under the new rules.

Digital rights campaigners said the law still has too many loopholes, saying that police and migration authorities – who are technically not allowed to use certain tools – will be able to secure exemptions from EU countries to continue using AI features such as real-time facial recognition in public places, especially when it comes to the most serious crimes.

Wicked

NIGERIA

Five Nigerian men who murdered a woman they accused of witchcraft were sentenced to death by hanging in the northern state of Kano this week, underscoring how traditional beliefs continue to clash with modern Nigeria, the BBC reported.

The five men had been accused of attacking Dahare Abubakar, 67, on her farm in 2023, beating and stabbing her to death, after the wife of one of the suspects had a dream in which the deceased was pursuing her. They were apprehended soon after.

This case riveted Nigeria, where in rural areas, the persecution or killing of an individual because they are suspected of witchcraft is still a common occurrence. Often, attacks arise after an individual blames another for using witchcraft to cause their misfortune, for example, an illness or a death in the family.

Belief in witchcraft is widespread across Africa. However, in Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, and South Africa, elderly people are often accused of being witches as a pretext for killing them and seizing their land, the BBC reported last year.

In countries like Nigeria, activists are working to put an end to such accusations and help protect the accused.

Meanwhile, even as prosecutors hoped the verdict would serve as a deterrent, the lawyer for the perpetrators said they would appeal.

DISCOVERIES

A Woman’s World

A Celtic society in Iron Age Britain took girl power to a whole new level.

While studying a 2,000-year-old burial site in the southwestern county of Dorset where the Celtic Durotriges people once lived, researchers from Ireland’s Trinity College Dublin and Britain’s Bournemouth University found that it was the women who were at the top of the social hierarchy.

They arrived at this conclusion after geneticists and archeologists from the research team tried to reconstruct the social structure of Iron Age Britain, which is difficult: Preserved remains are rare and the written accounts by Romans and Greeks are not reliable.

So instead, they analyzed DNA from more than 50 individuals from the site that was used before and after the Roman conquest of 43 CE. Their findings showed that kinship and inheritance were passed down through maternal lines.

“This was the cemetery of a large kin group,” lead author Lara Cassidy explained in a statement. “We reconstructed a family tree with many different branches and found most members traced their maternal lineage back to a single woman, who would have lived centuries before. In contrast, relationships through the father’s line were almost absent.”

This matrilocal social structure – where men moved to live with their wives’ families – showed that women played a central role in land ownership and social organization.

“This is the first time this type of system has been documented in European prehistory and it predicts female social and political empowerment,” added Cassidy. “It’s relatively rare in modern societies, but this might not always have been the case.”

The findings align with Roman-era writings about Britain’s powerful women. These writings documented famous figures, such as warrior queens Cartimandua and Boudica – the latter launched an armed uprising against the empire between 60 and 61 CE.

The texts were not always flattering nor very accurate, however.

“It’s been suggested that the Romans exaggerated the liberties of British women to paint a picture of an untamed society,” noted co-author Miles Russell.

The study also found similar maternal lineage patterns at other Iron Age burial sites, suggesting female-driven societies may have been more widespread across Britain than previously believed.

Other scholars welcomed the findings but cautioned against theorizing that this was a dominant pattern of societal organization across Iron Age Britain.

“It’s very interesting when you get something solid like this,” Lindsay Allason-Jones, an archeologist at Newcastle University who was not involved in the study told the Washington Post. “Given the paucity of Iron Age bodies, it’s really quite hard to say whether this covers the whole country.”