The Contagion

NEED TO KNOW

The Contagion

SOMALIA

On Feb. 1, US President Donald Trump ordered airstrikes targeting Islamic State (IS) jihadists in northern Somalia, where they have created a base for their operations in the country.

“These killers, who we found hiding in caves, threatened the United States and our allies,” Trump said. Regional authorities said the strikes killed “key figures” of the group.

The airstrikes on targets in the Golis Mountains of the northern semi-autonomous region of Puntland were the latest to target terrorists in the Horn of Africa country. However, in the past, they have usually taken aim at the larger, more entrenched al-Shabab militant group.

But now, the growing power of IS has led the Somali government and the international community to grow increasingly concerned because the group threatens not only Somalia but also the broader region, the Middle East, and elsewhere.

“It is clear the group is growing as a threat,” wrote analysts in a report for the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. “Over the last three years, the Islamic State’s Somalia Province has grown increasingly international, sending money across two continents and recruiting around the globe.”

“There are also growing linkages between the group and international terrorist plots,” they added. And in spite of being small compared to al-Shabab, the group “is punching well above its weight internationally and has become one of the Islamic State’s most important global branches.”

In 2015, when al-Shabab militants controlled large swathes of central and southern Somalia, a few dozen of the group’s fighters defected and pledged allegiance to IS. This offshoot of IS remained small until they staged attacks in the port city of Bosaso on the Gulf of Aden and elsewhere in the region in 2017. Afterward, the US launched its first strikes on the group.

The Somalia branch began to grow in importance after IS in Iraq and Syria was mostly defeated by 2017, and many of those fighters moved to Africa. IS in Somalia also attracted militants from other parts of the continent, especially Sudan, Ethiopia, Morocco, Libya, and Tanzania, as well as from Saudi Arabia and Yemen.

United Nations estimates put the group’s membership in Somalia at around 700 but local intelligence officials believe it’s as high as 1,600.

The Somali branch of the group is currently headed by Abdulkadir Mumin, who some US officials believe may be the new “emir” of IS globally – but others say he is not that high in the organization. Instead, they believe he is a key figure in the Somali branch but also may oversee IS affiliates in Africa and elsewhere. UN officials believe the Somalia branch may also oversee the terrorist group’s worldwide financial network.

Regardless, the group, which aims to create an Islamic caliphate in the Horn of Africa, is supported by IS in Yemen, which provides experts, trainers, money, weapons, and other materials, according to Australian security officials. “IS Somalia also taxes the local community, threatening harm if they do not pay,” they wrote. It recruits from the local communities, and raids those who don’t support them, it added.

The group is an enemy of al Shabab, which is allied with al Qaeda and the Houthis in Yemen.

On Dec. 31, after years of small-scale attacks, IS hit the military’s anti-terrorism unit in the Bari region of Puntland. It was a brazen attack, the most complex to date, and one that some say is an indication of the group’s growing confidence.

The attack came just after Puntland announced it would start an offensive against the group.

Soon afterward, fierce clashes broke out in Turmasaale in Puntland, a strategic location for IS because it is the militants’ main supply route, Voice of America wrote. The Puntland forces took the town and now want to dislodge the group from a nearby village.

Some analysts such as former Somali diplomat Abukar Arman say the threat of IS in Somalia is overstated, mainly to lure anti-terror funds to the country. Others dispute that characterization.

“The group’s power has not diminished – it is still quite strong,” former Puntland police chief and head of the intelligence agency, Abdi Hassan Hussein, told VOA. “And it is prepared for a long-term conflict.”

THE WORLD, BRIEFLY

Targeting the Targeters

WORLD

More than 70 countries condemned US President Donald Trump’s executive order Friday which imposed financial sanctions and visa restrictions on the International Criminal Court (ICC), warning that the move threatens the international rule of law and undermines accountability for war crimes, NBC News reported.

The US sanctions announced Friday target ICC staff involved in the issuing of arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Defense Minister Yoav Gallant issued in November 2024 over alleged war crimes in the Gaza Strip conflict.

The warrant also named Hamas leaders Yahya Sinwar, Mohammad Deif, and Ismail Haniyeh – all of whom were killed during Israeli operations last year.

The court accused Netanyahu and Gallant of using “starvation as a weapon of warfare” by restricting humanitarian aid and targeting civilians. Meanwhile, Hamas leaders are facing charges for the Oct. 7 attacks on Israel that killed around 1,200 people and resulted in more than 250 hostages taken to Gaza.

Israel and the US, both non-members of the ICC, dismissed the charges as politically motivated.

Trump’s order allows the US to freeze assets and restrict travel for ICC officials, with sources confirming that ICC Chief Prosecutor Karim Khan is the first official targeted. Trump defended the move as a response to “illegitimate and baseless actions” that endanger US personnel, while Netanyahu welcomed the decision, according to the Guardian.

The move drew condemnation from 79 countries, including US allies in the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Mexico.

French President Emmanuel Macron reaffirmed support for the ICC and German Chancellor Olaf Scholz warned the move “jeopardizes an institution meant to hold war criminals accountable.”

The United Nations human rights agency urged the US to reverse the decision.

With tensions rising, the ICC held emergency meetings on Friday, warning that US actions could disrupt its operations and threaten ongoing investigations, including those against Russian President Vladimir Putin for the abduction of Ukrainian children.

Ukraine also expressed concern that the US sanctions could undermine accountability efforts for Russian war crimes.

The US has had a complicated relationship with the ICC since it was formed in 1998: It was not involved in negotiating the 1998 Rome Statute that formed the court and also opposed the charter over concerns it “could subject US soldiers and officials to politicized prosecutions,” according to the Council on Foreign Relations.

In 2020, Trump imposed sanctions on former ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, who was investigating alleged war crimes by Israeli forces, Hamas, and the US military in Afghanistan.

The Biden administration lifted those sanctions in 2021.

Rage and Rejection

SLOVAKIA

Tens of thousands of Slovaks took to the streets over the weekend in the largest anti-government demonstrations in years, protesting Prime Minister Robert Fico’s pro-Russian stance and his suggestion that Slovakia could leave the European Union and NATO, the Associated Press reported.

On Friday, an estimated 110,000 demonstrators marched in 41 towns across Slovakia and 13 cities abroad, with Bratislava drawing around 45,000 people.

The protests, initially concentrated in urban centers, have now spread to rural regions traditionally supportive of Fico’s Smer party.

Demonstrators chanted “Resign, resign” and “Slovakia is Europe,” voicing anger over Fico’s recent visit to Moscow to meet Russian President Vladimir Putin – visits to the Kremlin by an EU leader are rare since Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine nearly three years ago.

Observers called Friday’s demonstrations the largest since 2018 when mass protests broke out over the murder of journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée, Martina Kušnírová. The protests led to the collapse of Fico’s previous government.

Fico, who survived an assassination attempt last year, has faced backlash since returning to power in October 2023.

His government ended military aid to Ukraine, opposed EU sanctions on Russia, and vowed to block Ukraine’s NATO bid.

In response to the protests, Fico accused Ukrainian and Georgian forces of orchestrating a coup, though he has provided no evidence. The Peace for Ukraine NGO, which helped organize the demonstrations, dismissed his claim, calling him “the main protagonist of Russia’s hybrid war in Slovakia.”

Protesters also accused the prime minister of harming Slovakia: The country is experiencing economic woes, a struggling education system, and deteriorating healthcare, Politico noted.

Despite the backlash, Fico dismissed the demonstrations.

He pointed to an EU statement affirming that Slovakia is not considering leaving the bloc and insisted that relations with Brussels remain “constructive and productive.”

The Belt Tightens

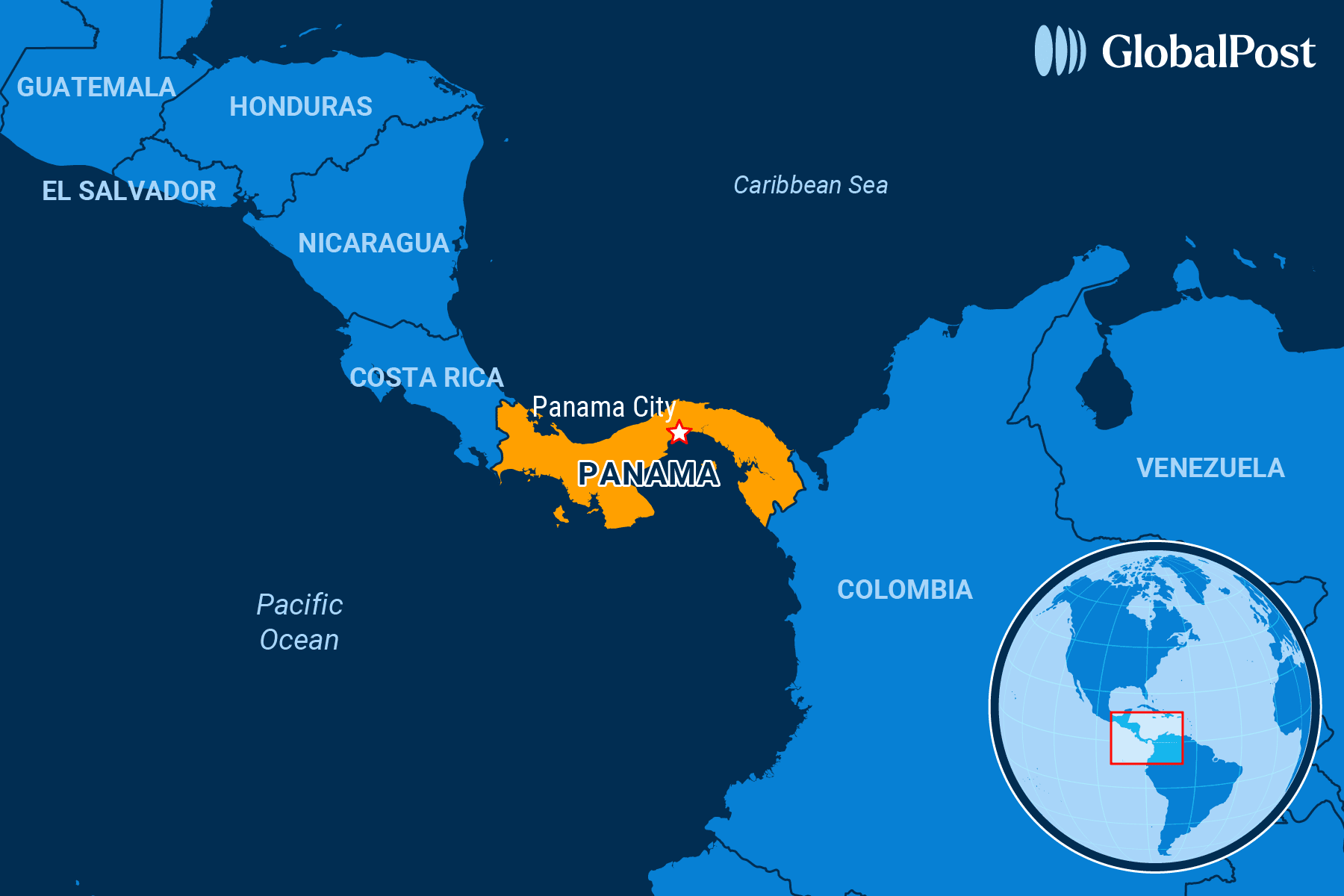

PANAMA

China accused the United States of “sabotage” over the weekend, shortly after Panama announced its decision to withdraw the country from Beijing’s trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) amid an ongoing row over control of the Panama Canal, Newsweek reported.

On Thursday, Panamanian President José Raúl Mulino said the country formally submitted a 90-day notice to withdraw from the ambitious global infrastructure program. He said the decision belonged to Panama and questioned what the BRI had brought the Central American country since it signed a memorandum of understanding with Beijing in 2017.

The announcement came before a weekend visit by US Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who later hailed Panama’s move as “a great step forward.” Mulino denied that the withdrawal was influenced by US pressure.

Chinese officials expressed “deep regret” for Panama’s withdrawal and urged the country to “make the right decision.” They also criticized the US for using “pressuring and coercion” to smear and sabotage the BRI, which has involved 150 countries since its launch in 2013.

Washington has accused the BRI of amounting to “debt trap diplomacy,” citing cases where struggling nations ceded key infrastructure to China after failing to repay loans.

The withdrawal comes amid recent disputes between Panama and the US over the Panama Canal, the crucial international shipping route that Washington ceded to the Latin American nation in 1999 after building it and administering the 51-mile waterway for decades.

The Trump administration has claimed that China has control of the waterway and has vowed to “take it back,” citing national security concerns.

China and Panama have denied the allegations.

A Hong Kong-based firm, Hutchison Ports Holdings, controls key ports on either side of the waterway. After the US expressed concern over Chinese control, Panama launched an audit of the company’s operations, Al Jazeera noted.

DISCOVERIES

Furry Solutions

Polar bears thrive in the extreme temperatures of the Arctic region. But for years, scientists have wondered how their fur remains ice-free.

Now they know – it’s all about the grease, according to a new study.

Researcher Julian Carolan and his team tested ice adhesion on washed and unwashed polar bear fur, and compared the samples human hair and synthetic ski equipment containing per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), which are used because of their anti-icing properties.

Their results showed that polar bear fur with its inherent grease resisted the buildup of ice just as well as human-made PFAS coating, while washed fur lost its ice-repelling properties.

The secret lies in a special oily substance called sebum, which coats polar bear fur and repels ice, the researchers said.

“The sebum quickly jumped out as being the key component giving this anti-icing effect,” Carolan said in a statement.

Carolan’s team found that polar bear sebum contains a unique blend of cholesterol, diacylglycerols, and fatty acids – but without squalene, a compound found in human and sea otter hair.

“Its absence in polar bear hair is very important from an anti-icing perspective,” Carolan noted.

This special coating also gives them an edge when hunting seals: They can slide stealthily across the ice using the low-friction properties of their fur.

Still, the discovery also has real-world implications in addressing the issue of PFAS – commonly known as forever chemicals. The material is used in non-stick cookware, water-resistant fabrics, and industrial coatings, but has been linked to cancer, infertility, and other health risks.

Extracting large amounts of sebum from polar bears – an already vulnerable species facing habitat loss due to climate change – is not a viable option.

However, now that scientists have identified the unique composition of polar bear grease, they aim to develop PFAS-free coatings that mimic its properties.

“If we do it in the right way, we have a chance of making them environmentally friendly,” co-author Bodil Holst told the Washington Post. “That is certainly the inspiration here.”