When a Faulty Peace Sows War

NEED TO KNOW

When a Faulty Peace Sows War

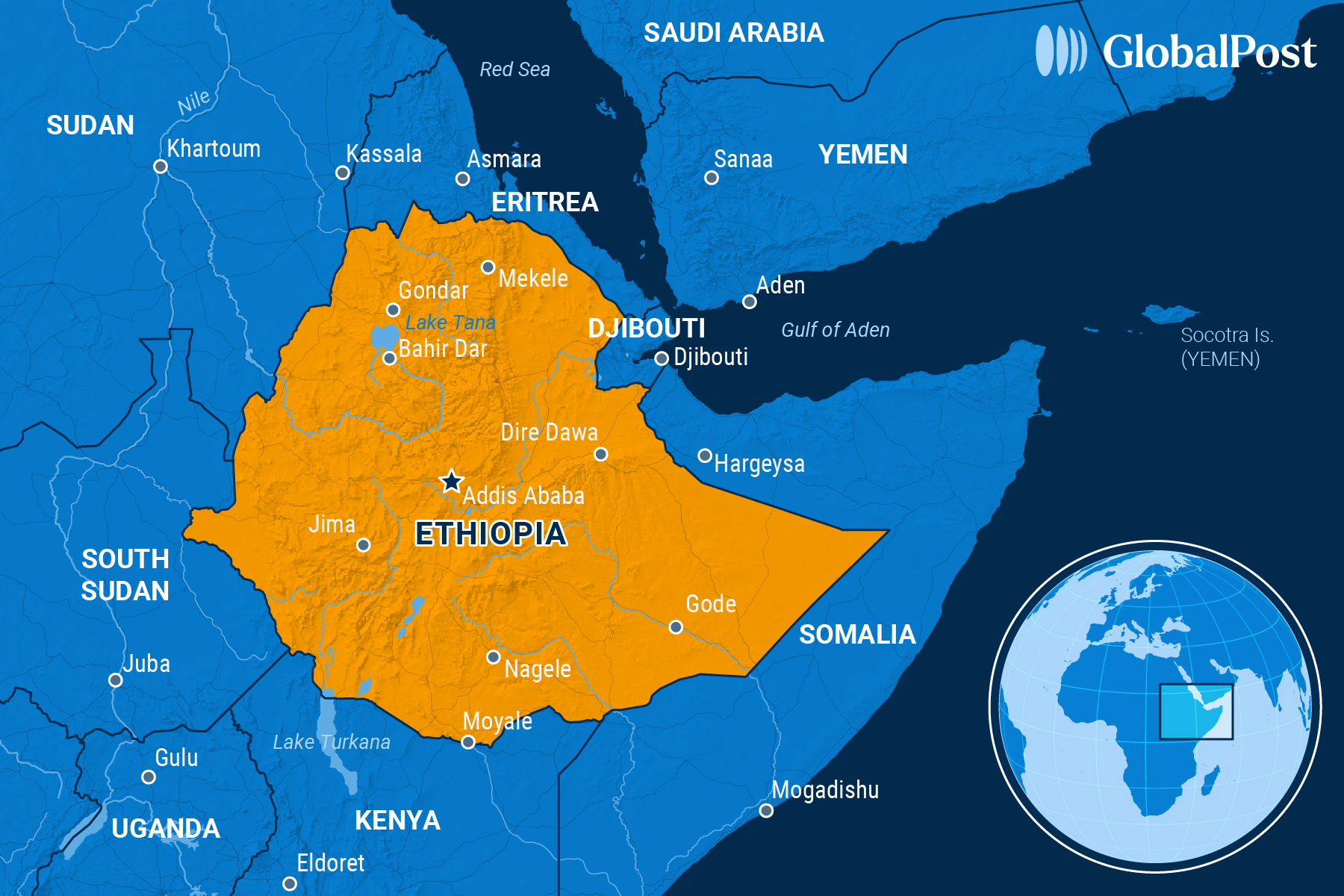

ETHIOPIA

In November 2022, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) signed a peace deal with the Ethiopian government, ending two years of an extraordinarily brutal war that cost hundreds of thousands of lives.

Now, war is brewing again in the war-torn semi-autonomous northern region but this time it’s likely to be sparked because of a growing power struggle between the two top officials in the region and issues left unaddressed by the peace deal.

“Some say the Pretoria agreement stopped the gunfire, but the genocide hasn’t ended,” Gebreselassie Kahsay, a lecturer at Mekele University in Tigray’s capital told German broadcaster Deutsche Welle.

The war in Tigray broke out in late 2020 after Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed launched a military operation to oust Tigray’s ruling party, the TPLF, a former Marxist-Leninist liberation movement that evolved into a political party. It had ruled the entire country with an iron fist for 30 years before being ousted in a popular uprising that brought Abiy to power in 2018. The region’s leaders had been defying Abiy and he had had enough.

To subdue Tigray, Abiy enlisted tens of thousands of fighters from Amhara, a region next to Tigray and also troops from Eritrea, which had been part of Ethiopia until breaking away in 1993.

The resulting war killed 600,000 people and displaced more than five million. Tens of thousands of women were raped and dozens of villages and towns were destroyed. The Ethiopian military’s complicity in war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide led to Western sanctions.

After the fighting mostly stopped with the peace deal, Abiy set up an interim administration for Tigray. However, he rejected Debretsion Gebremichael, head of the TPLF party, as leader of the region. Instead, the TPLF’s deputy chairman, Getachew Reda, who had led its delegation at peace talks, was chosen as president of the newly established Tigray Interim Regional Administration (TIRA).

As a result, in the fall of 2024, the TPLF expelled Getachew and 15 other party members. Getachew, in turn, accused them of planning a “coup” against the transitional government. Soon after, the two men and their supporters began feuding, a development that is now threatening the party’s existence and the region’s peace.

“Divisions within the Tigrayan ruling party…are now so deep, and the accusations being traded so vitriolic, there is a real possibility of their differences being settled on the battlefield,” wrote Martin Plaut of the Institute of Commonwealth Studies in the United Kingdom in Fair Observer.

Analysts say there have already been isolated incidences of violence involving the military in Tigray, whose members are increasingly choosing sides. At the same time, the region is being divided up between the two factions, leading to two parallel administrations.

Part of the problem is that the peace agreement hasn’t been fully implemented, causing more hardship and tensions, say analysts. For example, the government didn’t force the Amhara militias or Eritrean troops to leave Tigray as the peace deal dictated. As a result, they remain an occupying force in parts of Tigray, which means a million Tigrayans remain displaced, often in refugee camps.

The peace agreement also didn’t settle the issues between Tigray and the war’s two other main parties, Eritrea and the militias from Amhara, either. As a result, Abiy faces insurgencies at home and abroad.

One of those insurgencies is in the Ethiopian region of Oromia, a conflict that began in 2019 and has now become a “small-scale war” between the Oromo Liberation Army and the federal government. Another one is reigniting in Ethiopia’s Somali region: The Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF) has accused the Ethiopian government of abandoning a 2018 peace deal, alleging systematic suppression of Somali political participation and marginalization under Abiy’s administration. The ONLF has fought the government since 1984.

Then there is Amhara, which aided Abiy during the war with Tigray, and is now becoming a bitter enemy of the government. When the government tried to disarm its militias, known as the Fano, after the peace deal, they revolted and ignited fresh violence, which remains ongoing. Meanwhile, Eritrea began supporting the Fano.

That’s in part because relations between Ethiopia and Eritrea have broken down.

Seven years ago, Abiy made peace with Eritrea, won the Nobel Prize for his efforts and became the darling of the West. But after the peace deal, the two countries became enemies because Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki considered the peace treaty a betrayal.

As a result, most believe it is just a matter of time before Ethiopia and Eritrea go to war again. And any conflict between the two would involve Tigray whether it wanted to participate or not, given that it is sandwiched between both entities.

Still, as the Economist noted, Abiy has recently made overtures to the Tigrayans about a possible military alliance against Eritrea. Other Tigrayans are approaching Eritrea about joining forces to overthrow Abiy. The Fano brag they can overthrow the government alone.

“In this region there is never resolution of conflict,” Daniel Berhane, a Tigrayan intellectual told the magazine. “There are only realignments of forces.”

THE WORLD, BRIEFLY

Hunting the Hunter: Ex-Philippines President Arrested For Drug War

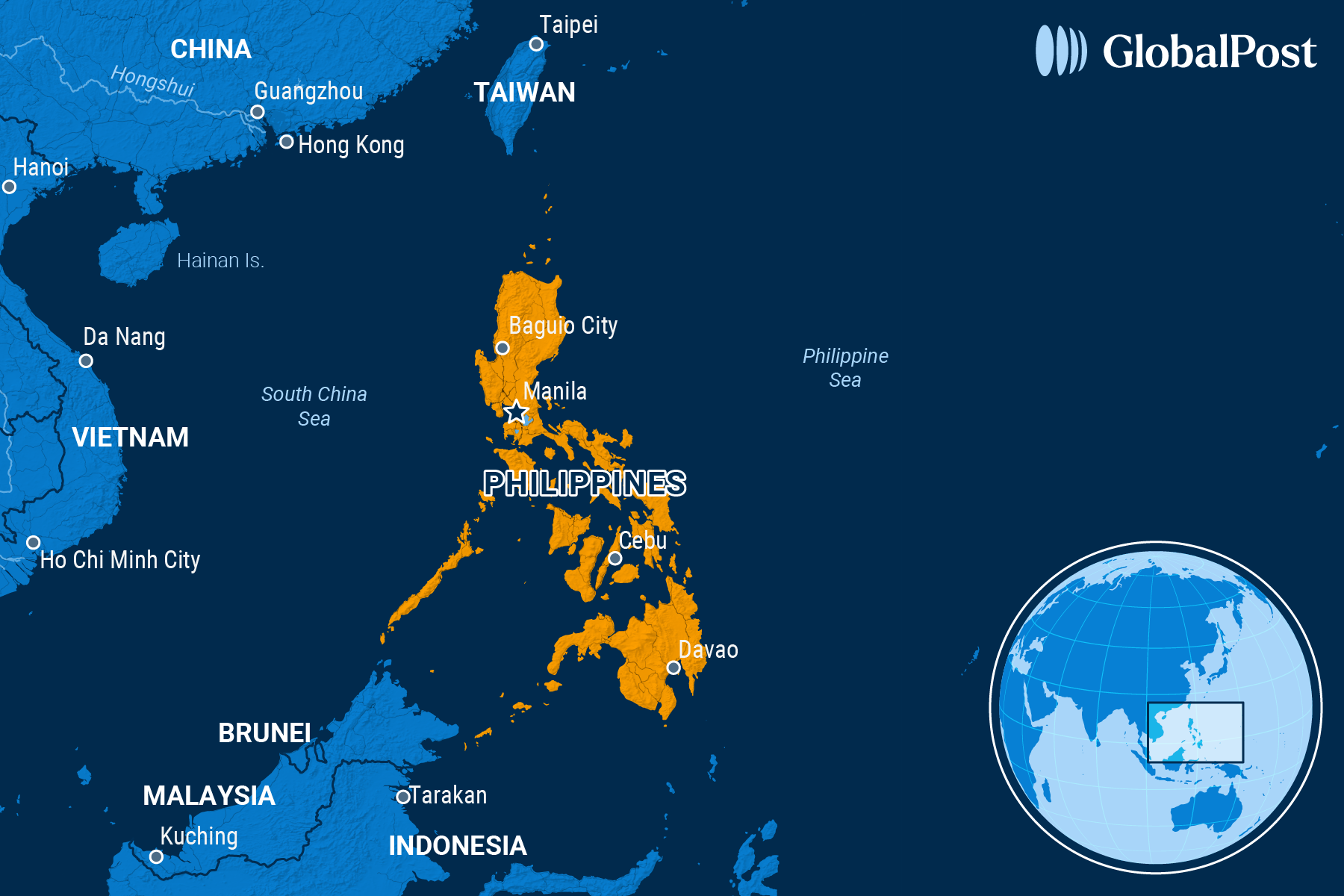

PHILIPPINES

Philippines ex-President Rodrigo Duterte was arrested Tuesday at Manila airport on an International Criminal Court (ICC) warrant accusing him of crimes against humanity, for acts committed during his war on drugs, which saw thousands killed and thousands more arrested, BBC reported.

Philippine police arrested the former leader in Manila and flew him to the Netherlands to appear at the ICC, the Associated Press reported.

The court in The Hague had ordered Duterte’s arrest through Interpol after accusing him of crimes against humanity over deadly anti-drug crackdowns he oversaw while in office.

Walking slowly with a cane, the 79-year-old former president turned briefly to a small group of aides and supporters, who wept and bid him goodbye, before an escort helped him into the plane.

The former president denied the charges, asking, “What crime (have) I committed?”

He also said on Instagram that he thought the Philippine Supreme Court would prevent his transfer to The Hague but added that he would “accept it” if an arrest were to come.

His daughter, Vice President Sara Duterte, expressed outrage. “This is not justice – this is oppression and persecution,” she said.

The Philippines withdrew from the ICC in 2019 under the Duterte administration. However, the ICC argued that it retains jurisdiction in the Philippines over alleged killing crimes carried out before the country’s withdrawal, as well as killing in the southern city of Davao at the time Duterte was mayor, France24 reported.

During his war on drugs, conducted during his presidency from 2016 to 2022, Duterte instructed police to implement a shoot-to-kill policy targeting alleged dealers. An estimated 5,600 young men, mostly poor, were killed – human rights groups estimate about 27,000 – and tens of thousands were jailed, often without being charged, Human Rights Watch wrote. About 100 children died as a result of this crackdown. Few of the deaths have been investigated.

A UN report found that police systematically coerced suspects into making self-incriminating statements under threat of lethal force.

He refused to apologize for his actions and insisted his policies prevented the Philippines from becoming a “narco-politics state.”

Duterte is still a popular political figure in the country. He is running for mayor of Davao again in May’s mid-term election.

Still, Duterte’s opposition, rights groups, and the families of those killed in the crackdown celebrated the arrest.

Coming Together: Kurds Agree To Be Part of Syria

SYRIA

Syria’s interim government reached a landmark agreement with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), one that would integrate the Kurds into national institutions while still allowing the minority group autonomy, in a deal that marks a significant step toward unifying the country, CNN reported Tuesday.

On Monday, Syrian Interim President Ahmad al-Sharaa, who signed the deal with SDF leader Mazloum Abdi in Damascus, said the agreement is aimed at “ensuring the rights of all Syrians in representation and participation in the political process and all state institutions based on competence, regardless of their religious and ethnic backgrounds.”

The deal establishes Syria’s Kurdish community as an integral part of the state and will grant citizenship to tens of thousands who were previously denied it under the Assad regime.

It also establishes a nationwide ceasefire, brings northeastern Syria under government control, and integrates Kurdish and Syrian military and civil institutions, including airports, and oil and gas fields, according to Al-Monitor.

The parties also agreed to combat remnants of ousted President Bashar Assad’s military, as well as pledge to reject hate speech and also work to prevent sectarian divisions.

Implementation is set to be completed by the end of this year.

The SDF was not involved in the rebel offensive that toppled Assad in December. However, it remains the most powerful non-governmental force in Syria and controls strategic territories in the northeast and most of the oil fields in Syria. The US-backed group played a key role in the fight against Islamic State.

The agreement follows an outbreak of violence between government forces and pro-Assad militias in the coastal regions of Latakia and Tartous, where more than 1,000 civilians – including members of the Alawite minority – were killed last week.

Analysts described the deal as a political win for al-Sharaa, who is working to consolidate power following the worst sectarian violence since Assad’s ouster.

Natasha Hall of the Center for Strategic and International Studies said that al-Sharaa is “playing a strategic game” by securing Kurdish support, particularly given the SDF’s strong ties with the United States and other international actors.

The integration could also help address Turkey’s long-standing concerns over Kurdish autonomy: Ankara considers elements of the SDF as affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which Turkey classifies as a terrorist organization. Turkey has been fighting the SDF with the help of Turkish-backed Syrian militias until recently.

Piper’s Coming: Victims of Apartheid Sue For Justice

SOUTH AFRICA

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa is expected to begin negotiations shortly to settle a lawsuit filed last month by survivors of apartheid crimes and families of the victims, News24 reported.

The 20 complainants argued that survivors and victims’ families were denied justice despite the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s recommendations to prosecute perpetrators. They say the prosecutions were blocked due to political interference and a secret deal between the African National Congress party and officials of the former apartheid government.

The applicants are seeking $9 million in damages and the establishment of a commission of inquiry into the crimes of murder, torture, and abductions carried out by apartheid security forces against them or their relatives that have never been prosecuted, Bloomberg reported.

Among those named in the case, Ramaphosa, the police department, and the justice minister are no longer opposing the case. The National Prosecuting Authority, however, still is.

Negotiations will start on March 17. The judge has urged all parties to settle by the end of the month.

Former President Thabo Mbeki, whose administration is among those named in the suit, has denied the accusations.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, set up by former President Nelson Mandela, recommended pursuing about 300 cases when it completed its work in the early 2000s. However, there have been only a handful of prosecutions since then.

DISCOVERIES

This Is Me

A woman may have carved her name into history – literally – on the world’s oldest dated runestone, according to new research.

Norwegian researchers analyzing a 2,000-year-old inscription suggested that a female rune inscriber may have left a rare signature, providing a unique window into the early development of runic writing.

The runestone, originally discovered in fragments at a burial site in Hole, Norway, carries a message that begins with the word “I,” followed by a name and a verb related to writing, before ending with “rune.”

“It’s a type of inscription also that has parallels in some other romantic inscriptions, basically somebody telling us that they made this inscription,” study co-author Kristel Zilmer told NBC News.

Zilmer and her colleagues explained that what makes this signature stand out is a feature in the name that indicates it ends with “-u” – a characteristic of female names in ancient runic script.

If confirmed, this would mark the earliest known example of a female rune carver, said Zilmer.

First uncovered in 2021, the fragments were found in different graves within a burial field, raising questions about their original purpose.

After more pieces were recovered two years later, researchers realized they fit together like a jigsaw puzzle, showing a series of runic sequences. Some markings appear ambiguous, suggesting the stone may have been engraved at different times by different individuals.

Radiocarbon dating of the cremated human remains and charcoal at the site placed the fragments between 50 BCE and 275 CE, making them the oldest known examples of runes inscribed on stone.

The team believes the artifact was likely part of a larger commemorative marker, possibly shattered and reused in later burials.

“Rune stones likely had both ceremonial and practical intentions,” Zilmer explained in a statement. “The grave field and the original raised stone suggest a commemorative and dedicatory intent, while subsequent use in a separate burial illuminates later pragmatic and symbolic expressions.”

Runes are a writing system used with Germanic languages based on the Roman alphabet until the Latin alphabet was adopted. It was widely used in Scandinavia until the late Middle Ages.

The authors said the findings reshape our understanding of the origins of runic writing and highlight the dynamic nature of early literacy in northern Europe.