Can’t Live With Them, Can’t Live Without Them: Russia’s Love-Hate Relationship With Migrants Leads To New Crackdown

NEED TO KNOW

Can’t Live With Them, Can’t Live Without Them: Russia’s Love-Hate Relationship With Migrants Leads To New Crackdown

RUSSIA

Russian officials have proposed hiking the fees that foreign laborers pay for the privilege to work in the massive country. The new fees would add to the bevy of bureaucratic hurdles that migrants face when working in offices and restaurants in cosmopolitan cities like Moscow and Saint Petersburg, or hazardous jobs like oil drilling or mining in Siberia, the Diplomat wrote.

Russian officials have proposed hiking the fees that foreign laborers pay for the privilege to work in the massive country. The new fees would add to the bevy of bureaucratic hurdles that migrants face when working in offices and restaurants in cosmopolitan cities like Moscow and Saint Petersburg, or hazardous jobs like oil drilling or mining in Siberia, the Diplomat wrote.

As in most Western countries, Russian officials are grappling with rising anti-migrant public sentiment and are moving to restrict foreigners moving to the Motherland – unless they are truly useful as weapons against their enemies, analysts say.

As a result, the proposals underscore Russia’s love-hate relationship with migrant labor. Russian lawmakers had already enacted laws earlier this year that allow officials to expel migrants more easily. This crackdown, however, occurred as the country needs foreign workers. Around 10.5 million migrants, mostly from Central Asia, are now employed in Russia’s “labor-starved economy,” the Moscow Times added.

The need arises because Russian families have been shrinking for generations, and the country faces demographic decline as low birth rates take their toll on the total Russian population of around 146 million. In 2024, births in Russia fell to 1.22 million – the lowest level since 1999 – while deaths increased by 3.3 percent to 1.82 million, according to official data. As Business Insider reported, the country faces a labor shortage of 11 million people over the next five years.

Putin has made population growth a national priority, calling it a matter of “ethnic survival” and encouraging women to have as many as eight children, the news outlet added.

Yet an animus against migrants in Russian politics – critics at Ukrainian news outlet United24 Media squarely blamed racism – drives the government to squeeze those who are among the most necessary to Russia’s economy – namely Central Asian migrants, who number about 10 million.

Last year’s deadly terrorist attack on the Crocus City Hall concert venue outside Moscow and the subsequent arrest of Tajik nationals suspected of carrying out the attack led to a spike in anti-migrant sentiment against Central Asians, with police raids on migrant communities across the country that saw tens of thousands of migrants detained. The situation was so dire and the harassment so extreme that it led the Tajik government to warn its nationals not to travel to Russia.

Still, there are certain situations in which Russia welcomes foreigners, usually involving its fight against the West.

For example, in recent years, it has opened its doors to “moral migrants” – those Westerners who relocate to Russia “in search of the traditional, conservative values they feel are eroding in the liberal West,” the Washington Post wrote.

“Their journey reflects the ideological narrative Putin has spent years crafting: Russia as the guardian of family-centered traditions amid a Western world spiraling into moral and social decay,” it added, noting their stories are used by Kremlin-backed influencers and in state media to shore up the propaganda exported abroad that Russia is a bastion of traditional values in an attempt to discredit the West.

Russia started two officials programs last year to promote moral migrants, seeing it as a “humanitarian mission”: The “shared values” visa – also known informally as the “anti-woke” visa – is available to individuals from 47 countries Russia considers unfriendly, including the United States, United Kingdom, and most of the European Union; and “Family – Russia,” focused on those who have chosen to leave the West and settle in Russia.

Meanwhile, Russia especially welcomes migrants to fight its battle with Ukraine as a way to avoid further conscription and upset the Russian public. As a result, thousands of migrants have been killed in a way they never expected to fight, and were often tricked or exhorted to do so, explained Radio Free Europe.

“The war in Ukraine has many fronts – but one of the most insidious runs deep inside Russia itself: through detention centers, migration offices, and construction sites, where thousands of Central Asian migrants are being recruited – or coerced – into dying for a war they never chose,” lamented the Atlantic Council.

It added that there are about 3,000 Central Asian migrants from within Russia serving on the front, the second largest group of foreigners after North Koreans leading to “body bags quietly sent home, pleas for help from the trenches, and recruitment videos shot behind barbed wire.”

THE WORLD, BRIEFLY

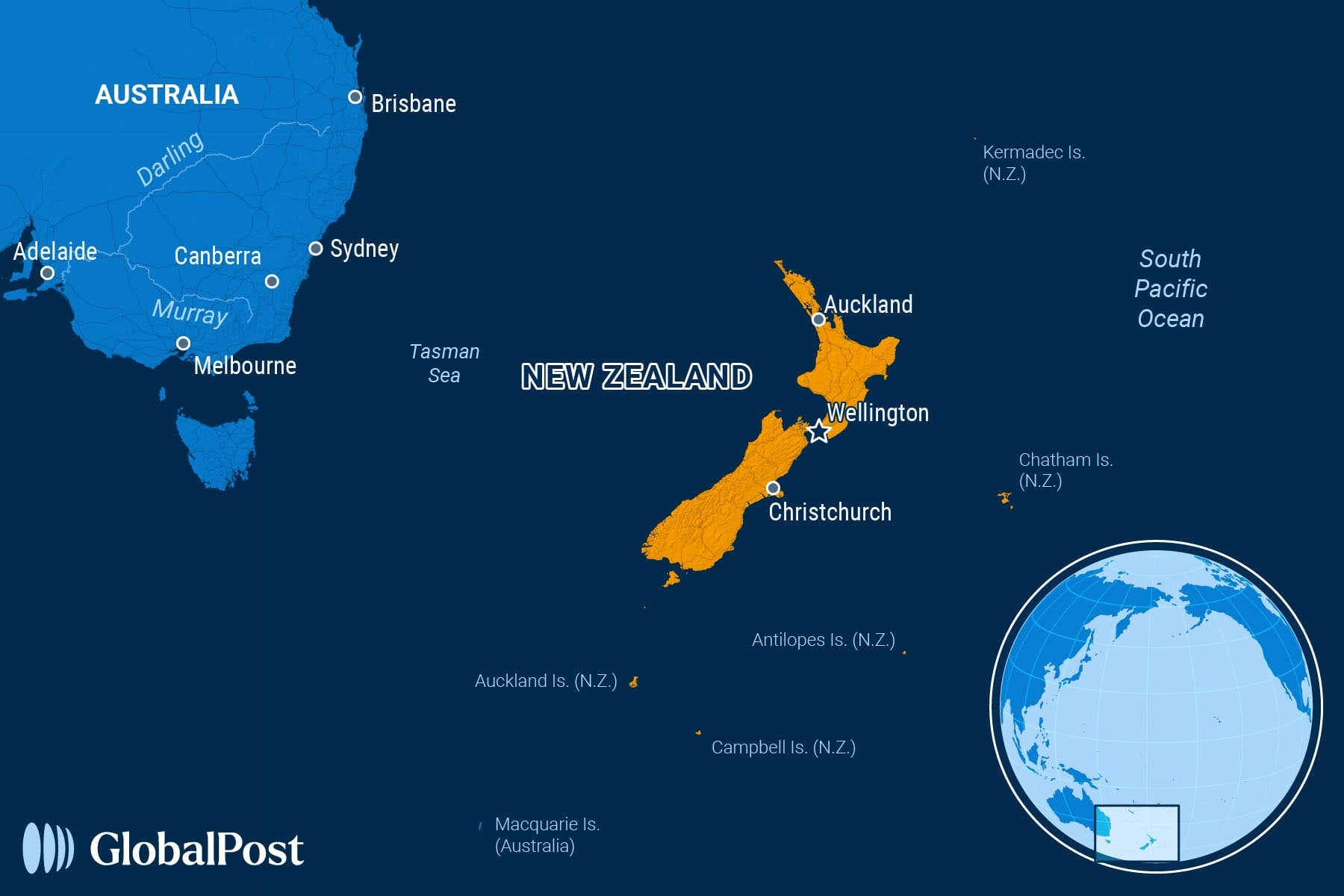

New Zealand Makes It Tougher To Vote, Critics Say

NEW ZEALAND

New Zealand lawmakers approved a bill Tuesday that would prevent individuals from registering to vote on election day and ban inmates from casting their ballot while in prison, a move critics say will lower voter turnout, Reuters reported.

New Zealand lawmakers approved a bill Tuesday that would prevent individuals from registering to vote on election day and ban inmates from casting their ballot while in prison, a move critics say will lower voter turnout, Reuters reported.

The proposed bill, which passed the first of three readings in parliament and will likely pass the next two, would require people to register to vote no later than 13 days before an election. Currently, eligible voters can enroll up to and on election day.

The measure would also ban those convicted and imprisoned for a crime from voting. That doesn’t include individuals accused of crimes and detained in a hospital or secure facility, Radio New Zealand explained.

The new law would take effect before the next general election scheduled for 2026.

New Zealand Justice Minister Paul Goldsmith, who proposed the bill, said it aims to modernize “outdated and unsustainable electoral laws,” adding that the changes are designed to strengthen the system by improving efficiency, clarifying regulations, managing costs, and ensuring quicker reporting of election results.

However, a report by Attorney General Judith Collins found that the bill “appears to be inconsistent” with New Zealand’s Bill of Rights, including the right to freedom of expression and the right to vote.

Lawmaker Duncan Webb, from the opposition Labour Party, called the bill “a dark day for democracy,” arguing that politicians should make the voting process easier for people and make sure that everybody can express their preferences.

The proposed amendments to the voting law were partly prompted by delays in releasing official results in the 2023 general election, when a high number of special votes delayed final results by nearly three weeks.

Special votes refer to ballots cast by New Zealanders who are overseas, by those who vote outside their usual electoral area, or by first-time voters. In the last election, that amounted to almost 250,000 votes out of an electorate of about 3.5 million.

Meanwhile, analysts also warned that the new bill may influence future election results in favor of conservatives.

Demonstrations Against Government Erupt in Angola

ANGOLA

Anti-government demonstrations involving thousands of people in Angola’s capital of Luanda turned violent this week, killing four, in one of the most disruptive waves of mass protests the country has seen in recent years, the BBC reported.

Anti-government demonstrations involving thousands of people in Angola’s capital of Luanda turned violent this week, killing four, in one of the most disruptive waves of mass protests the country has seen in recent years, the BBC reported.

The demonstrations, which continued Tuesday and closed major shops, banks, and businesses, arose from a three-day strike by taxi drivers over the weekend protesting rising petrol prices. It then morphed into anti-government demonstrations against the almost five decades of rule by the governing People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) party.

The protests were smaller than Monday’s demonstrations, where angry Angolans blocked roads, looted shops, torched cars, and clashed with police.

“The fuel price issue is just the last straw that has reignited widespread public discontent…,” local activist Laura Macedo told the BBC. “People are fed up. Hunger is rife.”

After Monday’s clashes, officials warned residents to stay home, describing the protests as “acts of vandalism” aiming to undermine the celebration of Angola’s 50th anniversary of independence.

The protests erupted after taxi drivers called the strike in response to the government’s decision earlier this month to raise the price of diesel by more than 33 percent. The move is part of efforts to eliminate fuel subsidies in the oil-rich country.

This price hike has not only led to higher taxi fares for Angolans, who rely on taxi services, but has also caused the prices of basic goods to increase.

Angolan President João Lourenço belittled these concerns, arguing that protesters are using the price hikes as an excuse to undermine the government. He added that even after the increase, the price of diesel in Angola remains one of the lowest in the world.

The average monthly salary in Angola is around $75, and the president’s promise to increase wages to around $120 has gone nowhere, critics say.

Colombia Convicts Former President Uribe for Bribery and Witness Tampering

COLOMBIA

A Colombian court Monday found Former President Álvaro Uribe guilty of witness-tampering and bribery of a public official, making him Colombia’s first former president to be convicted of a crime, in a landmark trial that has gripped the country, the Associated Press reported.

A Colombian court Monday found Former President Álvaro Uribe guilty of witness-tampering and bribery of a public official, making him Colombia’s first former president to be convicted of a crime, in a landmark trial that has gripped the country, the Associated Press reported.

After a nearly six-month-long trial, in which more than 90 witnesses testified, Uribe was convicted of attempting to sway witnesses who accused him of connections to a paramilitary group established by ranchers in the 1990s.

Uribe, 73, attended the trial virtually. He faces up to 12 years in prison.

He is likely to appeal the ruling and was seen shaking his head while the judge read her verdict, according to Agence France-Presse.

Uribe, who served as president from 2002 to 2010, is a polarizing figure in Colombia, and the trial was highly politicized, observers said.

Many credit Uribe with preventing Colombia from becoming a failed state, while others accuse him of human rights violations and the rise of paramilitary groups in the 1990s.

After the verdict was read, clashes erupted outside the courthouse between Uribe’s opponents and supporters.

Uribe’s case dates back to 2012, when he filed a libel complaint with the Supreme Court against left-wing senator Iván Cepeda, who had accused him of involvement with right-wing paramilitary groups that were deeply involved in Colombia’s longstanding conflict between government forces, guerrillas, and paramilitaries.

The court, however, did not prosecute Cepeda and instead turned its focus on Uribe in 2018.

Paramilitary groups in Colombia began forming in the 1980s as a response to Marxist guerrillas, who had been fighting the government in the 1960s, saying they were trying to end poverty and political exclusion in rural areas.

The armed groups, profiting off of drug and human trafficking, have been fighting each other in a deadly war that has led to spiraling levels of violence in the country.

Uribe, a right-wing politician, led a military campaign against drug cartels and the FARC guerrilla army, which signed a peace deal in 2016 with Uribe’s successor, Juan Manuel Santos.

DISCOVERIES

Primate Politics

It has long been assumed by both researchers and the wider public that sex-based inequalities in humans originate from their primate relatives.

A new study, however, has revealed that sex-based hierarchies in primates are more flexible than previously thought.

“Male dominance is not a baseline, as was implicitly thought for a long time in primatology,” study author Élise Huchard told the Washington Post.

Previous studies had already examined the female dominance spectrum in certain primate species.

The new research takes it one step further to precisely quantify the degree of one gender’s dominance over the other, according to a statement.

Scientists collected data from 253 populations representing 121 primate species to research contested interactions between males and females and analyze the context in which they tend to dominate.

These contested interactions included physical aggression to symbolic gestures signaling submission.

The team recorded which sex “won” each interaction, then compared the results across various primate species and populations.

In 70 percent of observed primate populations, neither females nor males were clearly dominant, meaning that they won more than nine in 10 interactions. Meanwhile, males were clearly dominant in 17 percent of primate populations and females in 13 percent.

“It’s actually a beautiful continuum, and most species lie in the middle and are not strictly male or female dominant,” Huchard said.

Females usually dominate in species where they have a strong hold on reproduction control, namely monogamous, arboreal species in which males and females are of similar size.

Female dominance is also more common in societies where there is strong competition among females or where conflict between the sexes poses less risk to smaller individuals.

Meanwhile, male dominance is particularly present in species where males have a clear physical advantage over females, namely in polygynous, terrestrial species and/or those living in groups.

“This study is part of a growing body of literature showing that when we think about power in animals as more than just who is biggest or baddest, when we recognize economic forms of power, such as the leverage that females derive from controlling reproduction, we find a wonderfully complex landscape of power,” Rebecca Lewis, a biological anthropologist not involved in the study, told the Post.

According to the findings, the so-called “alpha male” appears to be relatively rare across the 121 species observed, suggesting that male dominance among primates is not as ubiquitous as once thought.

However, primate behavioral ecologist Nicholas Newton-Fisher, who was not involved in the research, advised against relying too much on these study results to draw conclusions about humans, noting that, in the study, the primate group that includes humans is one that showed strict male dominance.

Even so, the study demonstrates that there is no universal model to explain power dynamics in primate societies, thereby opening new paths for understanding the evolution of gender roles in early human societies.