Casting a Spell: Attempted Murder of the President By Witchcraft Rivets Zambians

NEED TO KNOW

Casting a Spell: Attempted Murder of the President By Witchcraft Rivets Zambians

ZAMBIA

In mid-September, a Zambian court sentenced two men to two years of hard labor in prison for attempting to kill Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema – with sorcery.

The charges stem from an incident in December when a hotel cleaner in Zambia’s capital of Lusaka reported strange noises coming from a room. The two men were arrested after items such as a live chameleon, a mysterious white powder, a red cloth, and the tail of an unidentified animal were found among their possessions.

Afterward, the two men – one a Mozambican national and traditional healer, Jasten Mabulesse Candunde, and the other, a Zambian village chief, Leonard Phiri – were accused of being “witchdoctors” and were charged under Zambia’s Witchcraft Act with “possession of charms,” “professing knowledge of witchcraft,” and “cruelty to wild animals.”

Police say the two had been promised more than $73,000 by a political opponent of the president to bewitch Hichilema in a case that has gripped the nation.

Many Zambians take witchcraft very seriously: A study by the Zambia Law Development Commission in 2018 found that 79 percent of Zambians believed in witchcraft.

The criminal justice system also takes it seriously. In Zambia, under a colonial-era law, those found guilty of witchcraft face a fine or up to two years in jail, with the possibility of hard labor. However, witchcraft cases have been difficult to prosecute in the country because of difficulties in collecting evidence or finding credible witnesses.

This case was also tricky for prosecutors, who say the pair were hired by Nelson Banda, the brother of independent lawmaker Emmanuel “Jay Jay” Banda, to do harm to the president. Banda, who is facing trial for robbery, attempted murder, and escaping custody, was previously associated with former President Edgar Lungu from the opposition Patriotic Front (PF) party – Lungu lost the presidency to Hichilema in 2021.

The PF called the accusations against Banda politically motivated, while others alleged it was a stunt by Hichilema, who faces reelection next year. The president, who himself was accused of witchcraft by a past Zambian president a decade ago, has not commented on the case.

Some local media, however, blasted it.

“The president has nothing substantive to ride on to kick-start his second-term campaign – what better distraction from the economic crisis we face than a live viewing of a trial of ‘witches’ in the postmodern era,” wrote the Lusaka Times in an editorial. “Knowing Zambians fear witchcraft more than gunfire, the president hopes to score a major win. But the truth is…this trial will only expose him as a desperate figure, pleading for public sympathy while the whole world laughs at him.”

Still, the trial sparked huge interest in the country and highlighted the impact of the belief in witchcraft in the country. In Zambia, for example, there are “witch camps” where those accused of sorcery, usually elderly women, are placed if they have survived the accusations in their communities. There, residents live in inhumane conditions, say activists, and almost never return to their communities. Often, the women sit behind a fence, posing for tourists, often tied with ribbons to prevent them from flying away.

These so-called witch camps exist around the region, including in Mozambique, Tanzania, Malawi, and Ghana, where belief in witches is deeply ingrained and goes back centuries.

“The issue is persistent because of local beliefs,” Amnesty International West Africa researcher Michèle Eken told Newsweek. “It starts with a simple accusation…It can be because someone died in the village, and they are accused of being responsible. Or, tragically, the accusation can come from someone who has a debt to repay and does not want to pay it back or someone who wants their house/goods.”

While activists and some governments have tried to stop the stigma and punishment, other places in Africa, such as The Gambia, have carried out state-sponsored witch hunts in the past two decades.

Some, meanwhile, believe it is time to do away with the Zambian law that criminalizes witchcraft: It dates to 1914 when Zambia was part of the British “sphere of influence,” and does not reflect the country today culturally, they say.

“Traditional Zambian societies and individuals believe in a strong relationship between the human world and the supernatural,” Gankhanani Moyo of the University of Zambia told the Associated Press. “I hate that colonial piece of legislation that attempts to outlaw a practice that it does not understand.”

THE WORLD, BRIEFLY

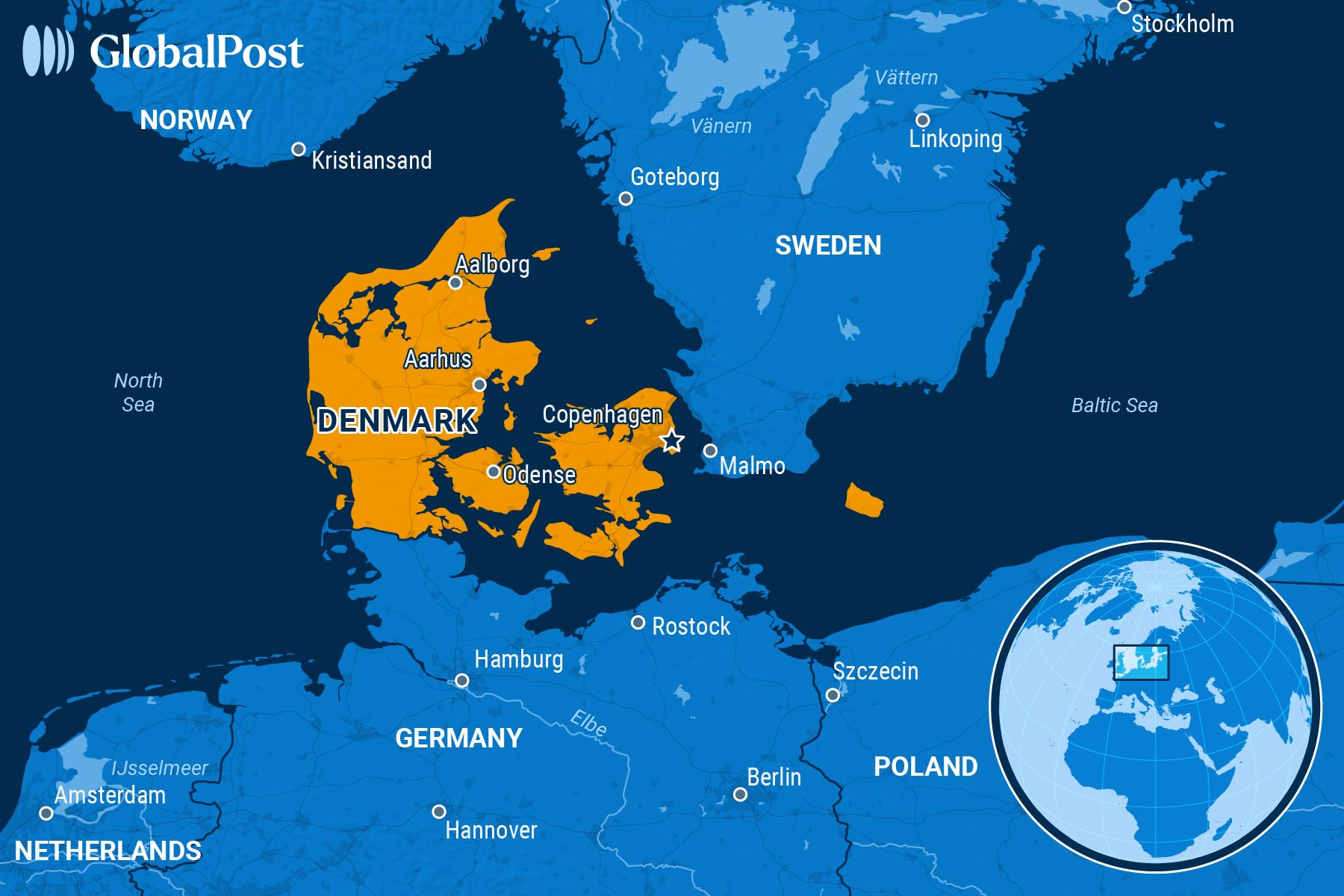

Denmark to Pay Reparations for Greenlanders For Forced Birth Control

DENMARK

Denmark this week officially apologized and announced reparations for Indigenous female Greenlanders who were forced to use contraceptive coils by Danish health authorities, and others in the country who were discriminated against, the Guardian reported.

Denmark this week officially apologized and announced reparations for Indigenous female Greenlanders who were forced to use contraceptive coils by Danish health authorities, and others in the country who were discriminated against, the Guardian reported.

During a ceremony in Greenland’s capital of Nuuk on Wednesday, Danish Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen and Greenland’s leader Jens-Frederik Nielsen offered their official apologies for their governments’ roles in forcing Greenlandic Indigenous women to have intrauterine contraceptive devices (IUDs) fitted against their will in cases dating back to the 1960s, according to France 24.

The alleged reason behind the forced contraception was to limit population growth in Greenland, which was rapidly increasing at the time, thanks to better health care and living conditions.

The Danish government said it would establish a fund to financially compensate these victims as well as other Greenlanders who have faced systemic discrimination.

Frederiksen had previously apologized for the IUD scandal for the first time in August. Then, Denmark and Greenland published apologies last month for their involvement in the abuse, ahead of the publication of an independent investigation into the matter that found that Inuit victims, some as young as 12, were either fitted with IUDs or given hormonal birth control injections without being given details about the procedures or asked for their consent.

The report covered the experience of 354 women, but Danish authorities say more than 4,000 – reportedly half the fertile women in Greenland at the time – received IUDs between the 1960s and mid-1970s, possibly longer.

The victims have been waiting for compensation for years. In 2023, about 60 of them sued the Danish government after a series of podcasts by Danish broadcaster DR exposed the extent of the campaign, the BBC wrote.

Shortly after the announcement of reparations, the Danish national appeals board said it was reversing a decision to separate a Greenlandic mother from her daughter one hour after she was born, following “parenting competence” tests that have often led to forced separations of Greenlandic families and have been criticized as racist.

In recent years, the IUD scandals and the “parenting competence” tests have drawn attention to Denmark’s treatment of Greenland. The Arctic island was a Danish colony until 1953 and remains part of the Danish commonwealth today.

Besides parenting tests and forced contraception, Denmark had other policies that discriminated against Greenlanders, including removing Inuit children from their parents and giving them to Danish families for reeducation.

Frederiksen’s announcement arrives amid international pressure, particularly from the US, which has repeatedly expressed interest in acquiring the self-governing territory. Meanwhile, Denmark’s efforts to placate Greenland’s independence movement have been overshadowed by past abuses.

Ecuador Rocked by Fuel Prices Protests as President Accuses Venezuelan Gang of Backing Unrest

ECUADOR

Farmers, Indigenous groups, and transport unions clashed with police in Ecuador this week while protesting over soaring fuel prices, with President Daniel Noboa accusing the Venezuelan drug gang Tren de Aragua of financing the unrest, Agence France-Presse reported.

Farmers, Indigenous groups, and transport unions clashed with police in Ecuador this week while protesting over soaring fuel prices, with President Daniel Noboa accusing the Venezuelan drug gang Tren de Aragua of financing the unrest, Agence France-Presse reported.

The protests stem from a decision Noboa made earlier this month to cut fuel subsidies, saying the move would save the country $1.1 billion. The measure resulted in diesel prices soaring from $1.80 to $2.80 per gallon.

Diesel is essential in Ecuador for agricultural machinery and transport, and demonstrators say the price increase is threatening their livelihoods, Euronews added. Nearly a third of the population in Ecuador lives in poverty.

Hundreds of Indigenous Ecuadorans on Tuesday took to the streets to demand the return of the subsidies, in defiance of a state of emergency declared by Noboa last week to contain violence and crime in the country. Demonstrators blocked major roads, disrupting food supplies and key sectors of the economy. However, the president warned that those who challenge the emergency would be “charged with terrorism” and be imprisoned for 30 years.

Ecuador’s powerful Conaie Indigenous group, credited with ousting three presidents between 1997 and 2005, said the protests were being violently repressed and urged supporters to “stand firm.” Organizers of the demonstrations said they expect more people to join in the coming days.

Noboa said that the protesters were “financed and surrounded by criminals from the Tren de Aragua.”

He posted a photo on X of several men behind bars – not clarifying who they were, why they were detained, or how they were linked to the protests – and wrote: “This is not a struggle, it’s not a protest … it’s the same mafias as always.”

Noboa has classified the Tren de Aragua as a terrorist group for its links to rising cartel violence in the country, mirroring a designation made by the United States.

Ecuador’s Minister of Government Zaida Rovira said Tuesday that 47 people had been arrested so far, including two foreigners suspected of links with the gang.

Greece Starts Trial Over the Country’s ‘Watergate’

GREECE

Four individuals went on trial in Greece on Wednesday, accused of involvement in a major wiretapping scandal dubbed “Greece’s Watergate,” a case that has shaken public trust and drawn international scrutiny, the BBC reported.

Four individuals went on trial in Greece on Wednesday, accused of involvement in a major wiretapping scandal dubbed “Greece’s Watergate,” a case that has shaken public trust and drawn international scrutiny, the BBC reported.

The Athens Criminal Court began hearing the case against the defendants – two Greeks and two Israelis – who face misdemeanor charges of violating the telecommunications secrecy laws.

If found guilty, they could face a maximum sentence of five years in prison.

The hearings come three years after a wiretapping scandal that involved Greece’s National Intelligence Service (EYP) and its targeting of the mobile phones of politicians, journalists, judges, and senior military officers with spyware.

The spyware, known as “Predator,” was marketed by Intellexa and can infiltrate a phone to access messages, photos, and remotely activate the microphone or camera.

Three of the defendants are former executives of Intellexa.

The scandal began in 2022 when Nikos Androulakis, leader of the opposition Pasok party, discovered that his phone had been targeted by the spyware.

Around the same time, Greek investigative journalist Thanasis Koukakis disclosed that he had been monitored first by Greece’s National Intelligence Service (EYP) and later by Predator through eight text messages, Agence France-Presse added.

Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis denied that the government was using the spyware, insisting that Predator was doing the targeting. But critics claimed that the overlap between Predator’s targets and those monitored by EYP suggested a coordinated surveillance effort.

Mitsotakis and his cabinet came under increased scrutiny for the government’s lack of willingness to probe who was spying on ministers and army officials. None of the serving ministers or military officers who were reportedly affected filed complaints or were called to testify.

The scandal resulted in the resignations of EYP chief Panagiotis Kontoleon and Grigoris Dimitriadis, Mitsotakis’s nephew and top aide. That year, Greece also passed a new law legalizing spyware use for state security under strict conditions, which critics say deprives citizens of the right to learn if they have been surveilled.

In 2024, the country’s supreme court concluded there was “clearly no connection” between the spyware and officials, a finding that watchdogs and opposition politicians have dismissed as political.

According to the Hellenic Data Protection Authority, at least 87 people were targeted by Predator, 27 of whom were simultaneously under EYP surveillance.

Analysts say the scandal casts doubt over Greece’s commitment to transparency and accountability within the European Union: The European Parliament called for strict rules to prevent the use of spyware, singling out Hungary, Poland, Greece, Spain, and Cyprus for allegedly using such software.

DISCOVERIES

Knots of the Empire

The Inca Empire of South America left behind some of the most striking monuments of the ancient world, from the soaring stone terraces of Machu Picchu to a vast road network crisscrossing the Andes.

But perhaps its most enigmatic legacy is the “khipu,” a system of knotted cords that encoded information without a written alphabet. Long assumed to be the exclusive domain of the elite, new evidence suggests these records may have been created by ordinary people as well.

The findings center on a recently analyzed khipu with a primary cord made entirely of human hair. Radiocarbon dating places it as being made around 1498, decades before the Spanish conquest.

Lead author Sabine Hyland wrote in the Conversation that she initially thought the strands came from alpacas or llamas, until her colleagues corrected her.

The cord in this case measured around three feet in length and took more than eight years to complete. That length provided scientists with a unique archive of the individual’s life: Analysis of the sample showed that the individual lived in the highlands of southern Peru or northern Chile and mainly subsisted on a modest diet of tubers, legumes, and grains.

These foods were not the typical diet of an elite Incan, which included meat and especially maize beer.

“It’s not really possible to escape drinking (maize beer),” Hyland told NPR. “Even today, in the Andes, when you participate in rituals, you have to drink what you are given.”

She explained that in Inca cosmology, hair carried a person’s essence. Incorporating it into a khipu could act as a signature, embedding the maker’s identity into the record.

Museums hold hundreds of khipus that remain unstudied. If others are found with similar signatures, they could challenge many of the records of Spanish colonizers to reveal a more complex history of Inca recordkeeping.

“This hair analysis adds another piece of evidence to the growing belief that khipu production and literacy might have been more widespread in the Inca Empire than the Spanish colonizers assumed,” co-author Kit Lee told NPR.

Harvard researcher Manny Medrano, who was not involved in the work, said the findings will help broaden the narrative around the Inca civilization.

“Ultimately, this gets us closer to being able to tell Inca histories using Inca sources,” he added. “We need to tell a story of literacy and of writing and of recordkeeping in the Inca Empire that is way more plural, that includes folks who have not been included in the standard narrative.”