NEED TO KNOW

Books, Traffic and Trauma

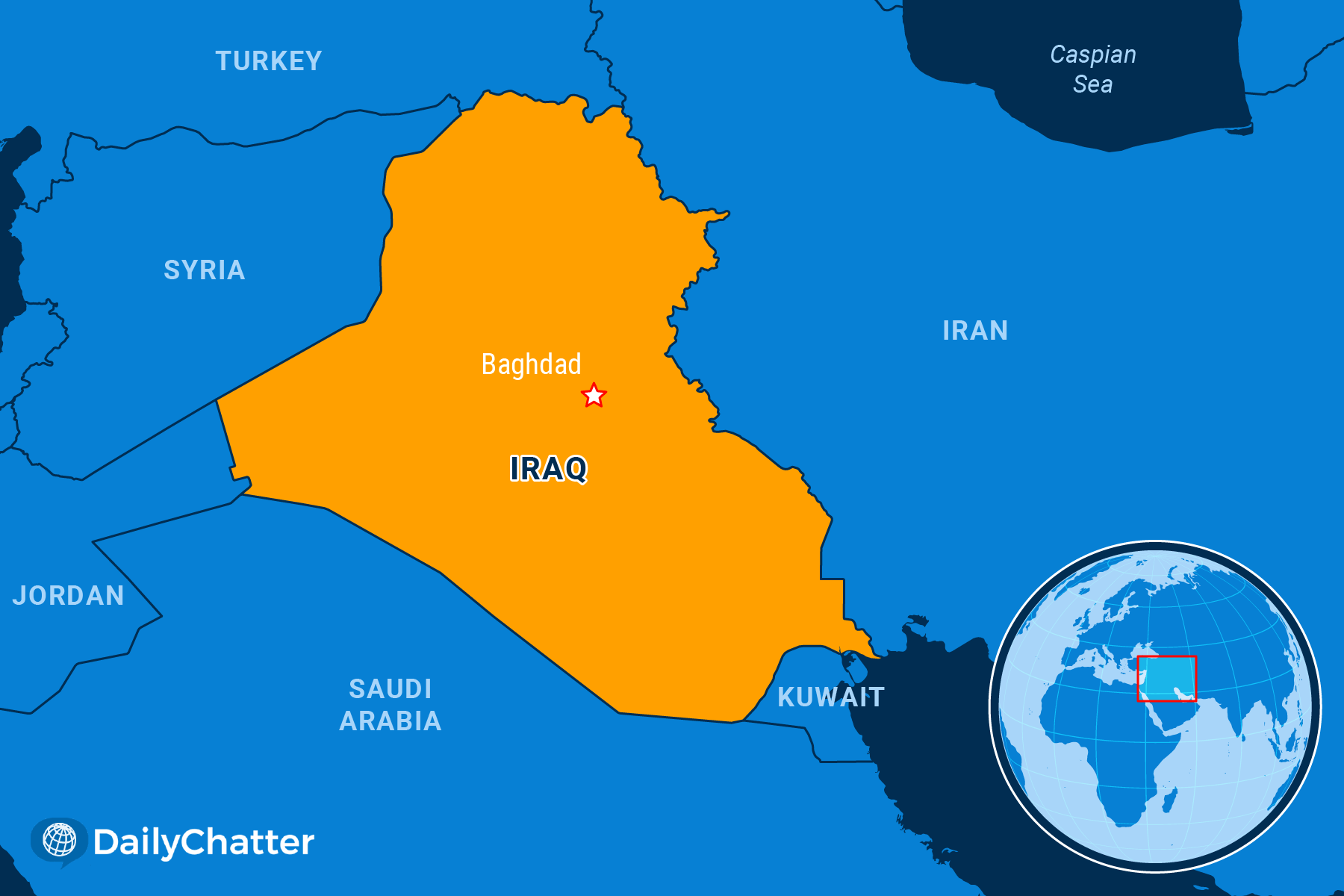

IRAQ

Twenty years after the American invasion of Iraq, the booksellers of Mutanabbi Street are back again, reviving the popular Arabic saying, “Cairo writes, Beirut publishes, and Baghdad reads.” Fighting in the streets kept the customers away from this otherwise well-frequented strip of booksellers during the early years of the 2003 invasion and subsequent unrest. Now, however, as Al Jazeera reported, Iraqis are returning to the Baghdad street, named as it is after the 10th-century Arab poet.

Some Iraqis are bitter about the turn of affairs, however. Why, they might ask, should they celebrate the revival of a shopping and cultural district, one that they would persuasively argue was needlessly ravaged because American leaders mistakenly – or insincerely – believed the country was stockpiling weapons of mass destruction.

As many as 120,000 Iraqi civilians died in the US-led war from 2003 to 2011, according to the Iraq Body Count. Approximately 80,000 died since then as armed groups filled the power vacuum that the exiting Americans created, helping give rise to the Islamic State terrorist organization. Today, around a third of Iraqi citizens are impoverished, Agence France-Presse reported. Corruption is rampant. Sectarian violence is commonplace in politics. Around 1.2 million people are still internally displaced.

Today, many Iraqis are working hard to process the horrors they experienced when the US and allied forces toppled former dictator Saddam Hussein and occupied the country, kicking off an insurgency that expanded to civil-war proportions. Authors, artists, and others have been working on projects to help people discuss and share their experiences in an attempt to get over them.

“We don’t have records, especially during the 2003 invasion when mobile phones and cameras, digital cameras, weren’t readily available for people,” United Kingdom-based Iraqi architect Sana Murrani told National Public Radio. “So there was this thing of trauma that lingers, trauma that is carried with you, and it resurfaces in very different ways.”

Even the one bright spot that arguably emerged after the war, a US-allied Kurdish autonomous region, is showing signs of deterioration, wrote Foreign Policy magazine.

Still, Iraq is making a recovery. It is a fledgling democracy, instead of a Sunni-led dictatorship led by Hussein, even if it’s a messy and often corrupt one. Violence has decreased significantly and new buildings go up as blast walls come down. Still, the economy is failing ordinary Iraqis, with a quarter living under the poverty line, and one-third are unemployed.

Just before the pandemic, thousands of Iraqis hit the streets in protest against poor services, the lack of electricity and other woes. While they were met with violence, they managed to bring down the government, the International Crisis Group noted. It’s likely that fury will bubble up again.

Meanwhile, one unintended consequence of the peace dividend is that Baghdad now has the worst traffic in the Middle East, which is no mean feat, noted the Economist. Before, bombs, terrorism and civil war used to keep Iraqis indoors; now it is the gridlocked traffic. As a result, commuters waste hours a day stuck in exhaust fumes. Residents do what they can to avoid pollution, not least by staying inside.

Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani, who took office in October, knows this is a problem, and has removed some checkpoints, moved to get traffic lights operational again and partially reopened the Green Zone, the district that the elite and diplomats had taken over since 2003.

Many of the walls built in 2003 in this district are coming down now, opening the area to ordinary Iraqis. The problem is, Iraqis need much, much more.

To read the full edition and support independent journalism, join our community of informed readers and subscribe today!