NEED TO KNOW

Greasing the Wheels

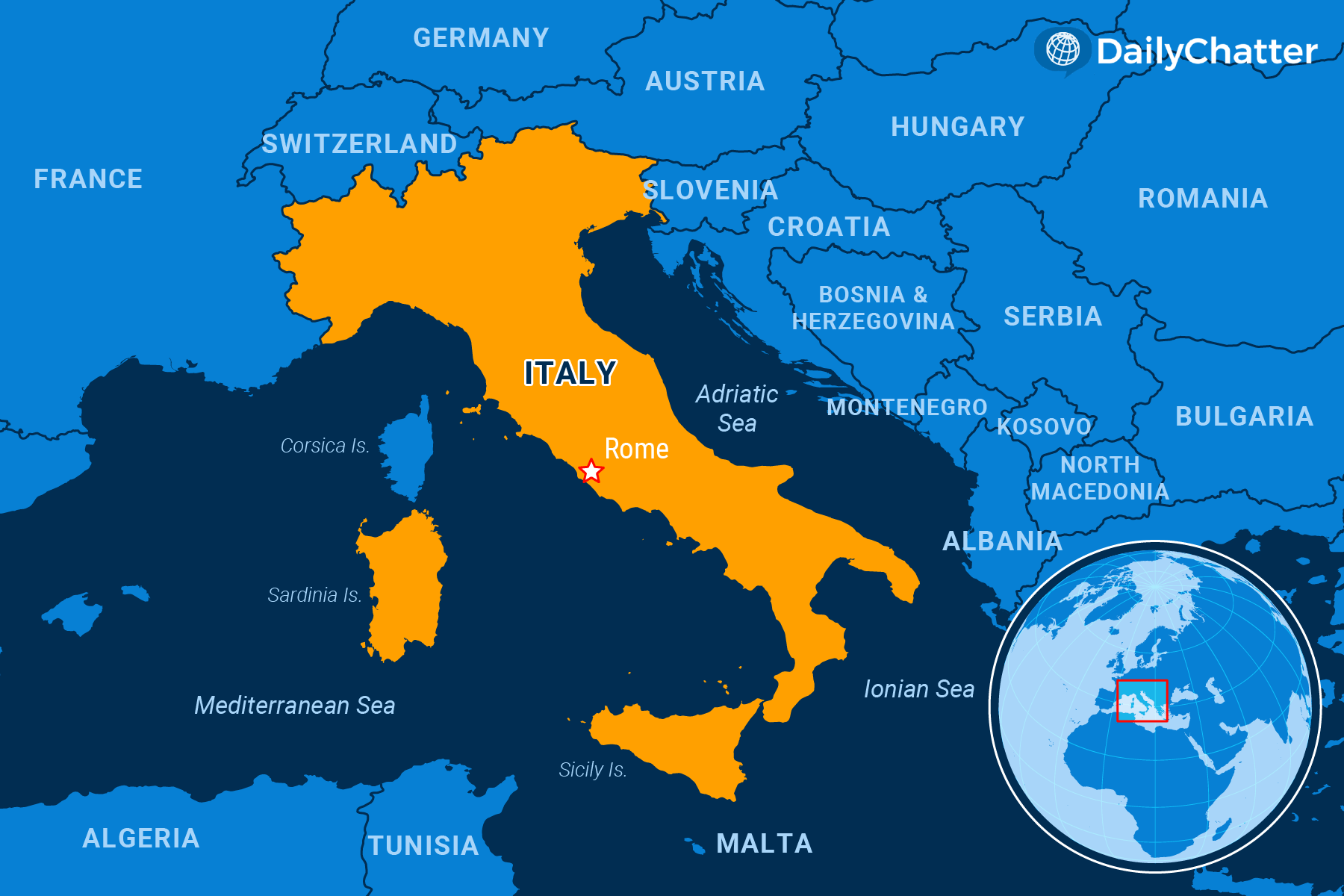

ITALY

The Italian judicial system took almost 20 years to determine whether a couple living near Genoa could compel their neighbors to stop flushing their toilet at night. Recently, the southern European country’s top court ruled in the couple’s favor, determining that the sound was interrupting their sleep and violating their human right to healthy living.

As the Washington Post explained, the tank of the toilet in question happened to be placed on the other side of a thin wall next to their bed’s headboard. The four men who lived next door apparently used the toilet frequently during the night.

This example illustrates how Italy has one of the slowest judicial processes in the European Union. Initial rulings take 500 days on average in civil cases. Appeals require another 800 days. Top court appeals are usually 1,300 days in coming. Criticism of how the judicial system has handled Catholic sex abuse scandals also suggests deeper corruption in the courts, too, the New York Times wrote.

The problem is deep. “The disarray in which the Italian civil justice system finds itself has been ongoing for decades, and red flags became apparent as early as the 1980s,” said University of Milan Law Professor Laura Salvaneschi, who is also a partner at the Italian law firm BonelliErede, in an interview with Law.com.

Italy’s increasingly complicated economy understandably requires more litigation, the Financial Times added. But the country’s legal system has helped undercut the productivity gains that should have resulted from that development. Italy’s gross domestic product has not gained in proportion in real terms – taking inflation into account – since 2000.

At the same time, the threat of endless litigation scares off foreign investors, constrains growing Italian companies and could keep Italy from qualifying for its share of a 200 billion euro ($250 billion) post-Covid recovery fund, the New York Times noted.

Now Prime Minister Mario Draghi is trying to change things. Launching what has been called “the mother of all reforms,” Draghi is pushing measures to decrease the length of civil trials by 40 percent in the next four years as well as cut other red tape that bogs down businesses and diverts Italians to courts rather than other means of resolving their disputes.

Among the reforms is a prohibition on magistrates from entering politics and then reentering the judiciary when their terms in office end, the Associated Press reported. The new rules, for instance, would prevent magistrates from running for office in regions where they were sitting on the bench or prosecuting cases in the previous three years.

The wheels of justice turn slow everywhere. In Italy, it seems like some have their foot on the brake.

To read the full edition and support independent journalism, join our community of informed readers and subscribe today!