NEED TO KNOW

No Quarter

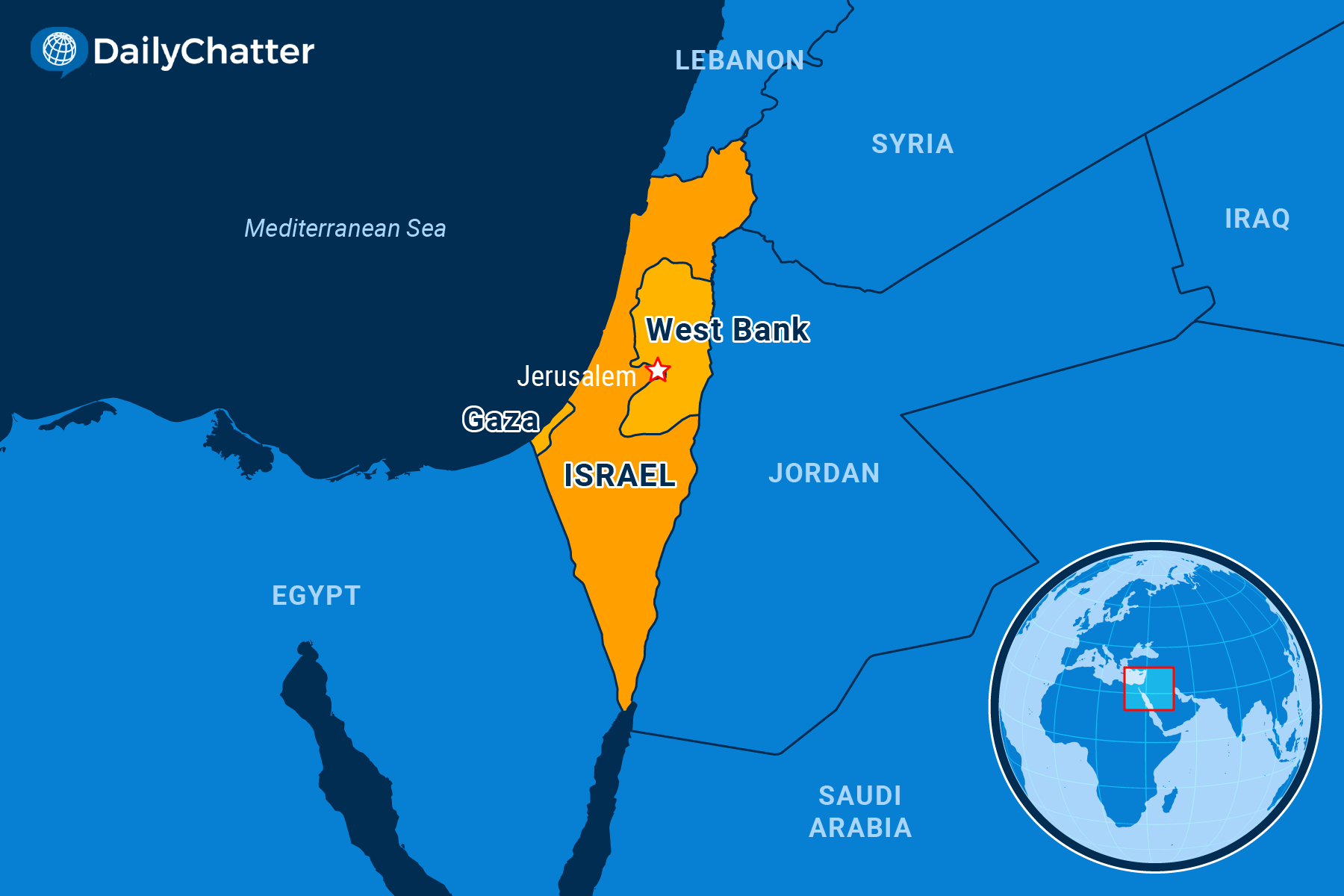

ISRAEL/ GAZA

When Israel gave the order to evacuate northern Gaza in advance of military strikes, Lubna and her four children had already left their home there to flee south to her friend’s house, knowing that safety was going to become ever more elusive.

She was all too correct, she says. These days, the sound of bombs is a consistent soundtrack to their new lives. Her friend’s house has narrowly missed being hit. So far.

“We are not the only family at the house now …We are sleeping seven ladies in the same room and the men (are) sleeping outside,” Lubna told the Guardian from Khan Younis near the Egyptian border. “There is no electricity or water,” she said. “The strikes are everywhere … When I say everywhere, (they are) literally everywhere.”

Lubna now is one of 1.4 million people who have been displaced since the devastating attacks by Hamas on Israel on Oct. 7 that killed 1,400 people, mainly civilians. Under siege since then, Gazans have been rationing food. Fuel and power are scarce. Many have already run out of water.

But it is safety that has become the scarcest commodity.

A drone flying over the Gaza Strip for USA Today captured the devastation that Israeli air strikes have wrought in the enclave abutting Israel, Egypt, and the Mediterranean Sea.

As of Monday, more than 5,000 Palestinians have been killed, almost half of them children, and more than 15,000 have been injured in the war. These tolls don’t include the hundreds of people who sought safety near the Al-Ahli hospital in Gaza City but died when a missile strike hit, the BBC wrote, noting that Israelis and Palestinians have blamed each other for the blast.

“Charred cars lining a parking lot. The courtyard littered with bloody blankets and backpacks. Tattered clothing where dozens of bodies had lain,” wrote New York Times reporters on the scene. “The smell of blood and burned metal hanging in the air.”

The destruction is the latest chapter in the sad history of Gaza, a 140-square-mile territory whose borders date to the Six-Day War of 1967 when Israel defeated a coalition of Arab countries that sought to destroy the Jewish state, Le Monde explained. Israel then controlled Gaza and its 2.3 million inhabitants until 2006, when Hamas won elections, ousting Fatah, the political organization that still controls the West Bank.

Israel responded by imposing a blockade on Gaza to prevent weapons and other non-humanitarian supplies from entering the enclave. While this blockade immiserated ordinary Palestinians – Slate was one of many publications that described Gaza as the world’s largest “open-air prison” – it apparently failed to prevent Hamas from obtaining missiles and other weapons, many of which came through hundreds of miles of tunnels constructed under the strip.

But it is keeping millions of Palestinians in, and in conditions so dire that the UN chief António Guterres called it a “god-awful nightmare.”

“It is impossible to be here and not to feel a broken heart,” he said at the border with Egypt over the weekend, waiting for the first aid trucks to be let in since the war began.

Israel’s ambassador to the United Kingdom, Tzipi Hotovely, disputed that the conflict has created a humanitarian crisis in Gaza, according to the Hill.

Many in the West agree that Israel’s cause is just, recognizing Israel’s right to defend itself and eliminate Hamas to make sure nothing like Oct. 7 ever happens again. But as demonstrations around the world and statements from leaders in the region, Europe and elsewhere start using the terms “war crimes” and “collective punishment” when talking about what’s happening in Gaza, it’s becoming clear that the backlash to the missile strikes could create more of the same in the future, wrote Washington Post columnist David Ignatius.

“Fighting Hamas is a just war, but it must be accompanied by a clear plan, framed by the United States and friendly Arab countries working with a new generation of Palestinian leaders, to rebuild Gaza and invest in the West Bank,” he wrote. “Otherwise, the war will create nothing but more rage in a barren land.”

Still, theoretical discussions about cause and responsibility and the future don’t matter much to mothers like Lubna, who has other things consuming her right now that are more important than rage.

She’s worried about food and water, and the bombs.

To read the full edition and support independent journalism, join our community of informed readers and subscribe today!