NEED TO KNOW

Old Wine, New Bottle

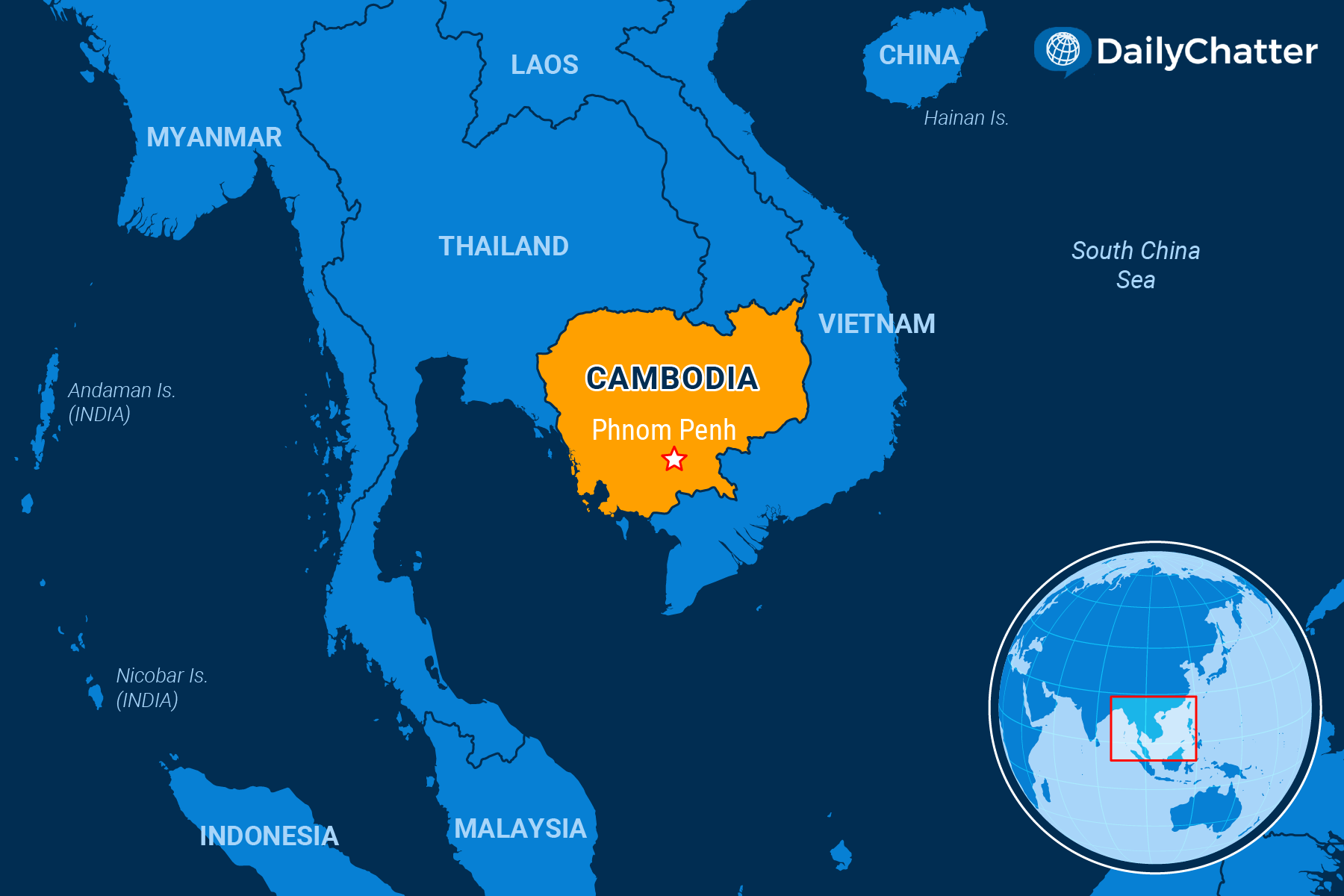

CAMBODIA

American diplomats recently registered their “serious concerns” about Chinese investments in the Ream Naval Base in southern Cambodia, the South China Morning Post reported. They fear the base could become part of China’s strategic network in the Indo-Pacific, according to the Diplomat.

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Manet likely ignored the complaints, instead celebrating the “ironclad friendship” between Cambodia and China when he met Chinese President Xi Jinping in October, wrote Xinhua.

Then again, Hun also met with French and Japanese officials in recent months. As the East Asia Forum explained, the Cambodian leader was likely trying to establish ties with leaders in Paris and Tokyo to cultivate other diplomatic influence beyond the rivalry between China and the US. Cambodian and French officials recently inked a $235 million aid agreement to improve Cambodia’s drinking water, energy systems, and vocational education, for example, added Voice of America.

These international developments have yet to satisfy pro-democracy activists and opponents of Hun’s ruling Cambodian People’s Party, however.

Hun became prime minister last year after his father, Hun Sen, who had been running the Southeast Asian country since the mid-1980s, stepped down following elections in July. The vote was a landslide victory for the Cambodian People’s Party, which won 120 of the legislature’s 125 seats. But it wasn’t fair. The country’s main opposition party, the Cambodia National Rescue Party, was banned from the ballot on technicalities.

“That electoral exercise was the latest in a series of falsified elections which serious independent observers have long since stopped bothering to observe,” argued the Geopolitics.

Hun Sen, incidentally, remained president of the senate, president of the king’s top council, and retained his position as president of the Cambodian People’s Party. His youngest son, Hun Many, became deputy prime minister. His other sons occupy key positions in the military while his daughters control vast shares in the country’s largest corporations, noted the Middle East and North Africa Financial Network.

Critics wondered aloud if Cambodia was not only a one-party state but also a one-family leadership in government, wrote the Union of Catholic Asian News.

“There is no democracy in Cambodia,” said Teav Vannol, president of the Candlelight Party, a successor to the Cambodia National Rescue Party, in an interview with Nikkei Asia. Government critics based in Australia who advocate for democracy also claim the Cambodian government has targeted them, reported SBS News, a quasi-public Australian broadcaster.

That shouldn’t surprise anyone, wrote Human Rights Watch, which added that the transition from father to son was expected to retain the status quo. Meanwhile, the situation has actually become worse.

Attacks against opposition and government critics continued after the election and were similar assaults in 2023 against Candlelight Party members. On March 3, a court found political opposition leader Kem Sokha guilty of treason and sentenced him to 27 years in prison and indefinitely suspended his political rights to vote and run in an election.

“The political transition to Prime Minister Hun Manet,” said Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director at Human Rights Watch, is just putting ‘old wine in a new bottle’ when it comes to human rights and democratic freedoms in Cambodia.”

To read the full edition and support independent journalism, join our community of informed readers and subscribe today!