NEED TO KNOW

Past and Present

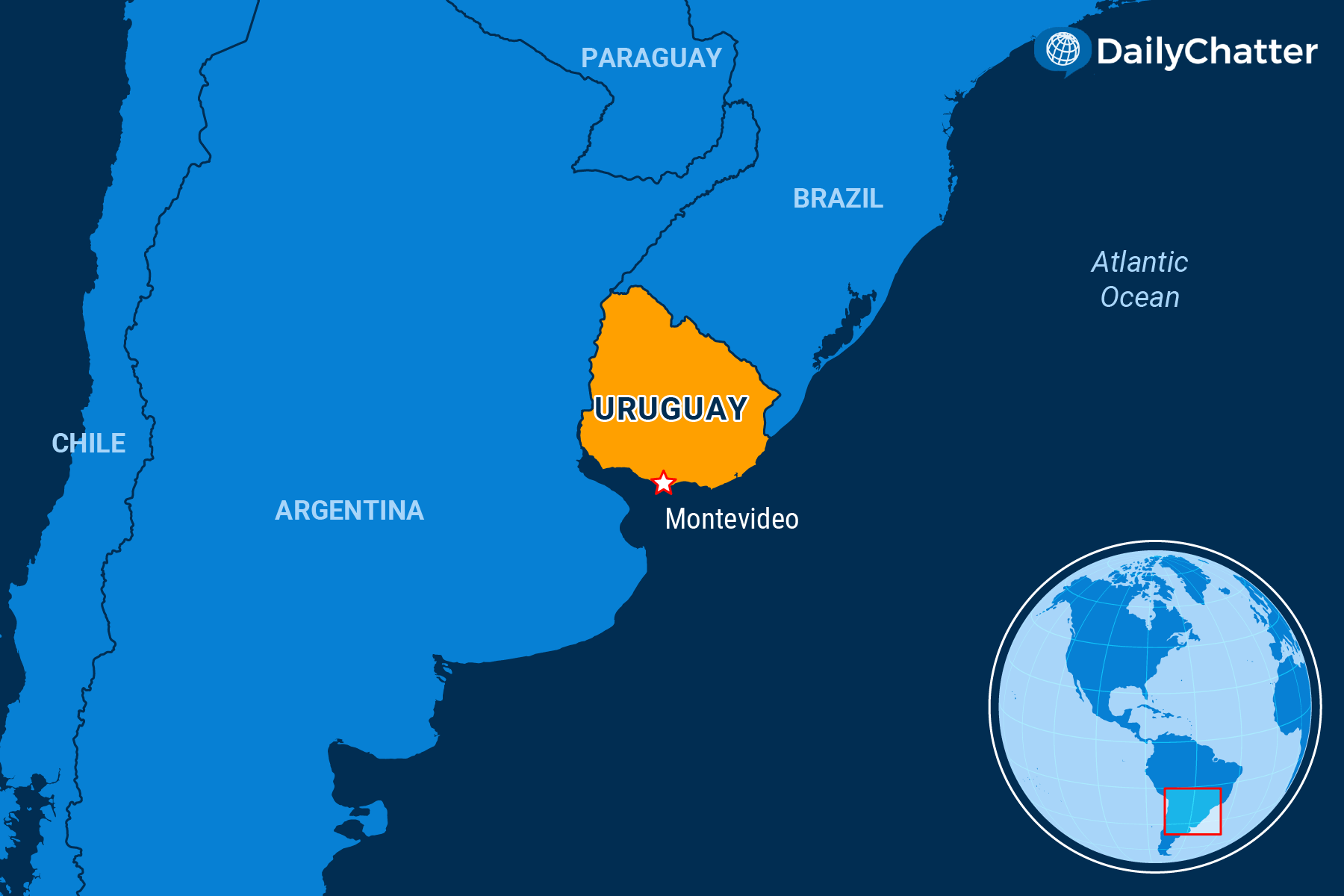

URUGUAY

The Admiral Graf Spee was a German warship scuttled in 1939 in Montevideo Bay in Uruguay after the Battle of the River Plate, the first major naval battle of World War II. In 2006, treasure hunters searching the bay discovered a 770-pound bronze eagle that once adorned the heavy cruiser. In its talons, the eagle is clutching a swastika, a feature that understandably stirred controversy in the South American nation.

As the Washington Post explained, current President Luis Lacalle Pou wanted to destroy the artifact. Others persuasively argued that it was an important historic relic that officials should preserve as it can relate vital lessons about the past. Nobody knows what to do with it now.

Uruguayans today are similarly immobilized when it comes to their own past. In 1973, a coup installed a dictatorship and military junta that launched a crackdown on Marxist rebels, resulting in the imprisonment of 6,000 people, France 24 reported. The junta fell in 1985. Today, though, around 200 people known as the “disappeared” have yet to be found.

These days, Uruguay, on the one hand, is a success. It generates 95 percent of its electricity from renewable sources like solar and wind, the Economist noted. The Institute for Economics and Peace, an Australian think tank, ranked the country this year as the safest on the continent.

The country is not perfect, of course. A severe drought following years of underinvestment in water infrastructure has led to salty, gritty tap water in the capital Montevideo that caused an uproar, the Associated Press reported. On another level, a court recently sentenced Pou’s former chief bodyguard, Alejandro Astesiano, to more than four years in prison for using his position to corruptly arrange for Uruguayan passports for Russian citizens, added MercoPress.

But, to many Uruguayans, these relatively mundane issues pale in comparison with their desperate need to find the remains of the “disappeared”, and bring the former soldiers and police officers who were their kidnappers and murderers to justice. Every year on May 20, thousands of people march through the capital in silence carrying photos of the “disappeared” to commemorate their victimhood, wrote Global Voices.

“We need that whoever has information to deliver it,” said Alba Gonzalez, the mother of one of the disappeared. “It’s urgent to break the culture of silence and impunity.”

In 1986, however, Uruguay passed a law that in effect gave amnesty to the monsters who tortured and killed their fellow citizens, argued Francesca Lessa, a Latin American specialist at Oxford University, in the Conversation.

Uruguayans are in the impossible situation of holding despised memories they can’t easily forget.

To read the full edition and support independent journalism, join our community of informed readers and subscribe today!