NEED TO KNOW

Strongman Down

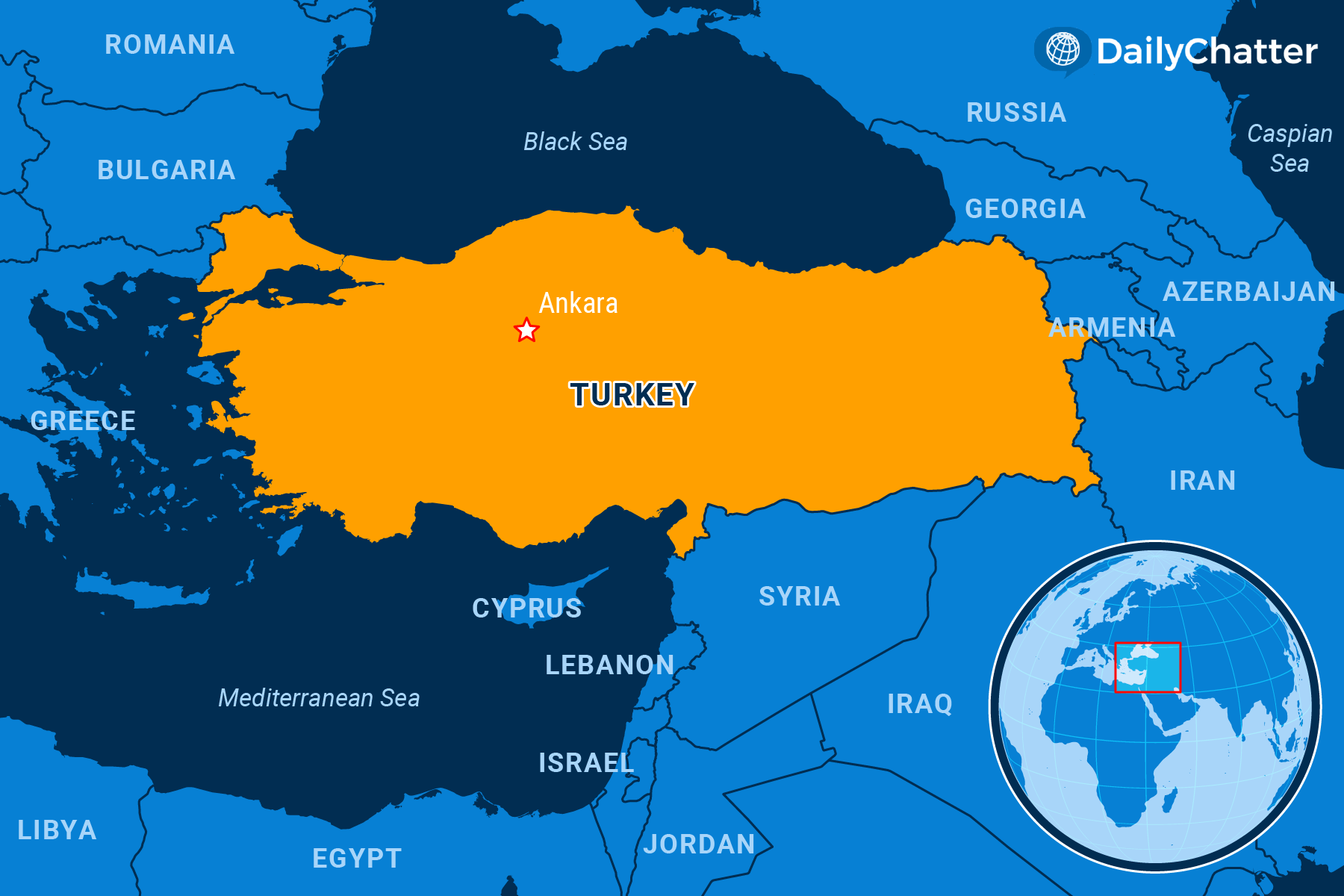

TURKEY

Turkish politicians have been appealing to voters in the Mediterranean city of Mersin in the run-up to the country’s presidential elections on May 14. Mersin is the capital of a swing province whose residents could decide the seemingly tight race between President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has led the country for 20 years, and opposition leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu.

The race has been labeled the most important election of 2023.

Erdogan faces a challenge because inflation has been running at an annual rate of almost 44 percent in Turkey. Mersin is especially contested, however, because many people in the city have suffered the destruction of the devastating earthquake that hit Turkey in February, reported the Financial Times. Many Turks are outraged at the lack of building safeguards that led to the catastrophe, and the corruption that allowed this situation to happen.

Serdar Tatar, a butcher in Mersin, voted for Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party in the past. Now he’s supporting the president’s rival. “There is no prosperity … the rich get richer, the lower class is crushed,” said Tatar. “I will vote for Kilicdaroglu.”

As the Journal of Democracy explained, Erdogan rose to power as an “anti-establishment everyman” who wanted to revive Islam in a nominally secular Turkey, revive his country’s geopolitical heft, and expand the economy. Today, he’s widely considered to be an authoritarian who has clung to power by undermining human rights and ensuring that he and his allies dominate the civil service, judiciary, economy, and other facets of Turkish society.

A former accountant in the Turkish Finance Ministry who was named “Bureaucrat of the Year,” Kilicdaroglu ran the country’s social security system before joining parliament in 2002, wrote National Public Radio.

He has been pledging to bring liberty back to the country, often in homemade videos from his kitchen that speak directly to voters, for example, with him waving an onion to rail against inflation, which is widely blamed on Erdogan’s unorthodox economic policies. It’s the only way to be heard in a country where the media solely focuses on what the leaders want it to focus on, or else.

That repression in the press also extends to speech: Turks, for example, can be imprisoned simply for insulting the president, a charge that has been leveled more than 200,000 times during Erdogan’s tenure. Kilicdaroglu wants to change that, he says, telling voters that they would be free to criticize him. “The youth want democracy,” he said in an interview with the BBC. “They don’t want the police to come to their doors early in the morning just because they tweeted.”

Some voters are reluctant to drop Erdogan, however, the Washington Post added, noting how his message still appeals to conservative, middle-class voters outside Turkey’s major cities who feel ignored by the secular, metropolitan elite. “Erdogan does have his issues, but I don’t find his opponent to be a real opponent,” one voter told the Post. “All they do is criticize what Erdogan does and they don’t say anything productive.”

Part of the incumbent’s appeal is also how Turkey has become a decisive actor throughout the region, from helping to broker an agreement to allow Ukrainian grain to flow to the international market, supporting forces vying for control of Libya, and negotiating with Europe over housing the millions of Syrians and other migrants who have left their war-torn homes in the past decade – newcomers that many Turks want out now.

And then there are the grand projects – or rather, distractions, say critics. As the Economist noted, Erdogan, over the past month alone, has inaugurated the country’s first nuclear plant, celebrated the tapping of a big gas field in the Black Sea, jumped behind the wheel of Turkey’s first electric car, and unveiled its first aircraft carrier. “If you’re wondering why he still hovers at more than 40 percent (in the polls),” Galip Dalay, an analyst, told the magazine, “one reason is this idea and this language of grandeur.”

Meanwhile, there are fears over what will happen if the leader loses – Erdogan has meddled in elections before. The May 14 poll surely won’t be free and fair, argued Foreign Policy magazine. But Kilicdaroglu can nevertheless still win if he secures a wide enough lead.

If Erdogan loses, it will be another end of an era for the storied nation.

To read the full edition and support independent journalism, join our community of informed readers and subscribe today!