NEED TO KNOW

The Bombs of Ambition

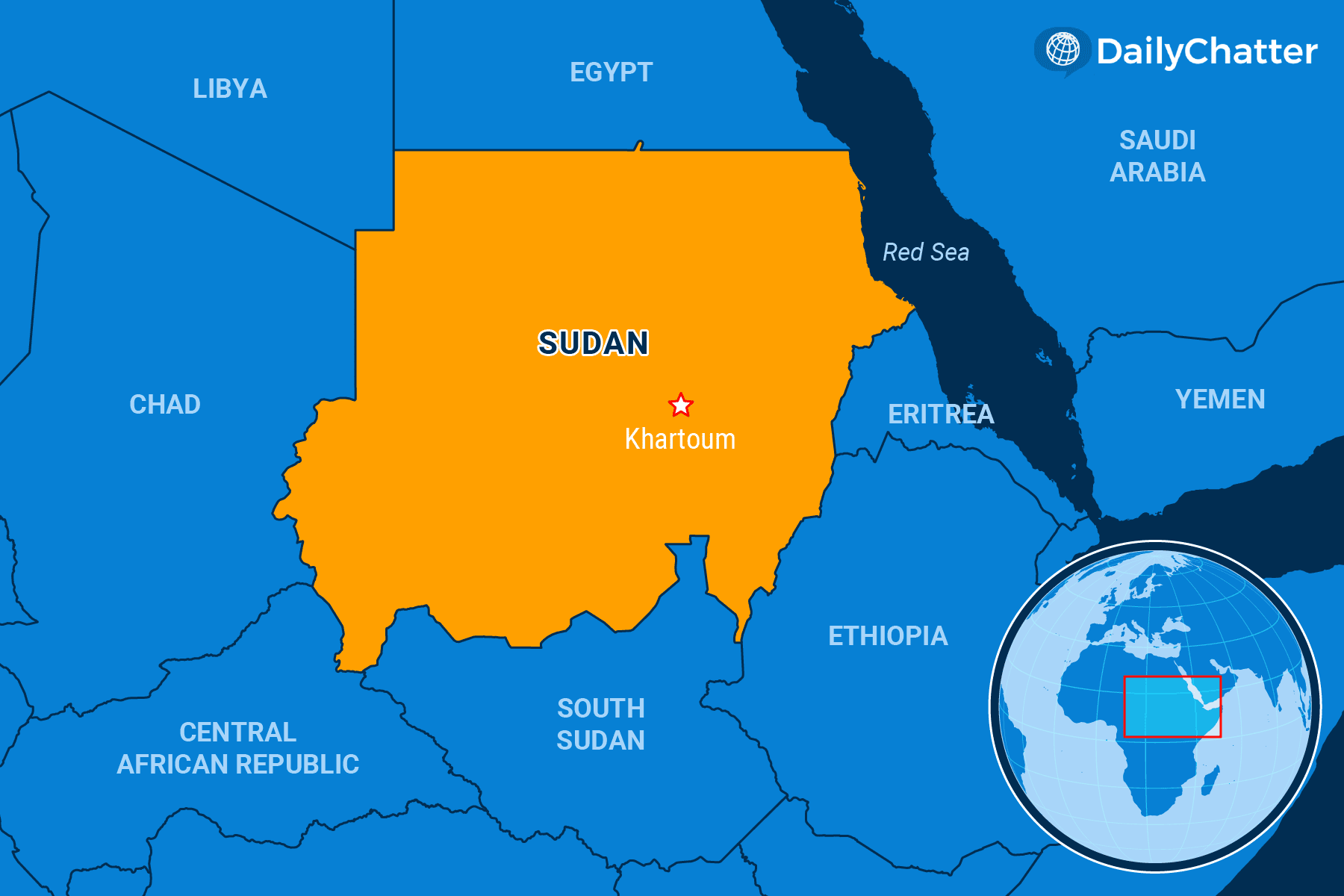

SUDAN

This week, downtown Khartoum became a war zone. Fighters have been attacking residents, United Nations workers and other civilians, sexually assaulting women, and looting and destroying property, CNN reported. Health officials are warning that the country’s hospitals are running out of medicine to treat the wounded. Many of them lost power and closed. Meanwhile, ambulances are being attacked in the streets.

A video showed how the sound of gunfire and bombs has replaced the city’s soundtrack of traffic and chatter.

Hundreds of people have been killed, tens of thousands have fled to neighboring South Sudan and Chad. Those left behind are now just trying to survive.

Khartoum resident Duaa Tariq saved her last bottle of potable water for her two-year-old. “This morning we ran out (of water),” she told the BBC. She detailed how she and her family have been sleeping on a mattress in a hall – the safest place in her house. “Most of the people [that] died, died in their houses with random bullets and missiles, so it’s better to avoid exposed places in the house.”

Essentially, the choice for civilians is hunger or bombs, the Washington Post noted.

The civil war in Sudan between government troops and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary group, that broke out last week is threatening to destroy the country that both sides are seeking to control.

And both men have amassed war chests over the past few years, while controlling significant portions of the country’s economy and resources.

The war stems from a power struggle between Sudan’s nominal leader, military junta head Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, who seized power in a coup in 2021, and Gen. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti, the commander of the RSF, a group linked to the Janjaweed militias who stand accused of committing crimes against humanity in Darfur in the early 2000s. Both sides have accused the other of attempting to pull off a coup, noted Deutsche Welle.

In an interview with National Public Radio, Jeffrey Feltman, former US special envoy to the region, said the bloody conflict reflected both men’s “lust for power.” The two were in a “marriage of convenience” after they worked together to oust former President Omar al-Bashir in 2019. For around two years, Sudan was a pseudo-democracy with a transitional government that featured civilian officials, but then Burhan staged a coup and took control. Now, Hemedti wants more influence.

In particular, argued University of Washington historian Christopher Tounsel in the Conversation, Hemedti was deploying RSF fighters around the country without the Sudanese army’s input.

And meanwhile, foreign hands were stirring the pot, especially Russia’s Wagner Group, Libya, and Egypt. Now, analysts worry that Sudan’s implosion could impact the region, destabilizing “Chad, the Central African Republic, Libya and South Sudan, which are all already scarred by conflict to varying degrees,” wrote the International Crisis Group. “Further, Sudan is riddled with countless other armed groups and communal militias, any or all of which could throw in its lot with Burhan or Hemedti, turning a two-sided war into a much more complex free-for-all, especially in the country’s peripheral areas.”

Tounsel cited an African proverb to describe the situation: “When the elephants fight, it is the grass that gets trampled.”

Similar violence and results have unfolded throughout Africa since the 1950s, contended Al Jazeera’s senior political analyst Marwan Bishara. Generals unseat dictators on pledges of national revival, prosperity, and democracy. They then fall into disputes with their allies, triggering gunfights that morph into civil wars.

And the grass doesn’t get a chance to recover.

To read the full edition and support independent journalism, join our community of informed readers and subscribe today!