A Spoonful of Salt

Gambian Ebrima Sagnia, 44, in an emotional interview with Al Jazeera, recalled how in 2022, he gave the cough syrup to his four-year-old son to combat his high temperature. The boy became drowsy and couldn’t urinate for days. He suffered kidney failure, swollen limbs, nausea, confusion and other painful symptoms for around a week before dying.

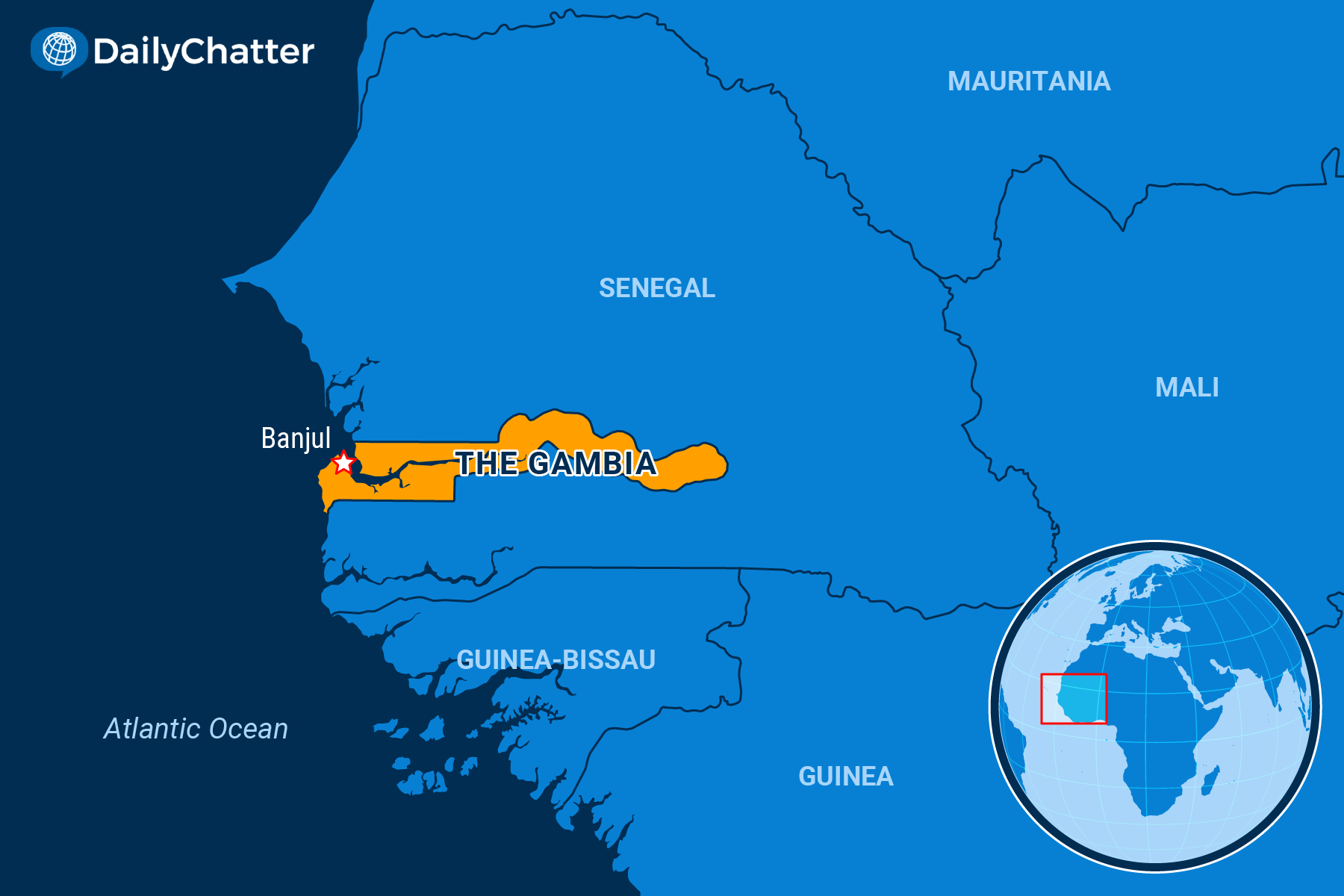

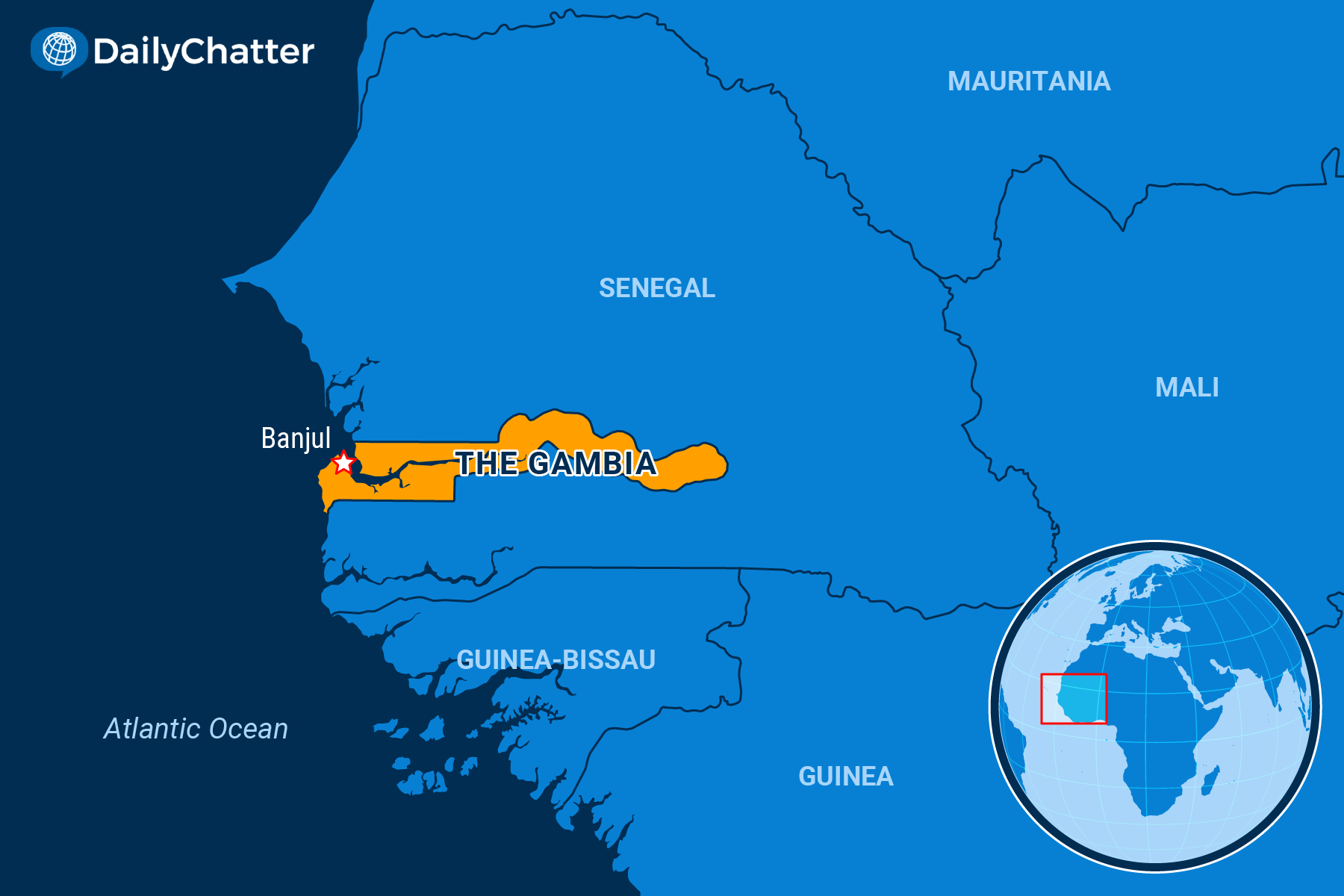

He was just one of 70 victims in the West African country, most of the others also being younger than five, who died after taking Indian-made cough medicine. Some families lost more than one child. Many drank syrup from bottles emblazoned with false World Health Organization (WHO) certifications.

The development highlighted the lax oversight in the medical trade between India and developing countries that rely on foreign, especially Indian, drug suppliers.

Even so, the parents of these young victims have been fighting back, launching lawsuits to hold the company accountable for its alleged mistakes and threatening one of India’s key industries.

Already, Indian officials are due to announce whether they intend to take action after investigating allegations that Indian regulators took bribes in exchange for approving toxic cough syrup that killed all those children in the country.

India-based Maiden Pharmaceuticals was likely involved in the production of the medicine, reported Reuters, citing the WHO. Indian government scientists said they didn’t find toxins in the medicine, however. The company has denied wrongdoing.

“There is no evidence and no proof against us,” said Maiden founder Naresh Kumar Goyal, according to Indian news outlet NDTV, a claim echoed by Indian lawmakers. “I have not given a bribe.”

Even so, India has since made drug testing mandatory for cough syrups before they are exported.

That’s surprising, say experts, given how important the industry is for the Indian economy: India is the world’s largest producer of generic drugs and exported medicines worth $25.4 billion in 2023.

Public health advocate Dinesh Thakur and attorney Prashant Reddy T, authors of “The Truth Pill: The Myth of Drug Regulation in India,” told National Public Radio that India produced 20 percent of the world’s drugs, including 60 percent of vaccines used globally. Rising demand for cheaper generic medicines, or knock-offs of well-known branded drugs, is growing the industry further, especially as many countries can’t pay Western prices for medicine.

Still, the cough syrup scandal in the Gambia is not the first to rock the Indian pharmaceutical industry. In December 2022, for example, Indian pharmaceutical company Marion Biotech allegedly sold cough syrup in Uzbekistan that killed 18 children suffering with acute respiratory diseases, reported Frontline, a news magazine affiliated with the Hindu newspaper.

Also that month, Nepal blacklisted 16 Indian pharmaceutical companies because authorities said that they failed to comply with the WHO’s quality manufacturing standards. In the US, the Food and Drug Administration said in April 2023 that an Indian firm linked to US eye drop deaths broke safety norms.

Still, prosecuting Indian drugmakers in India is difficult, Thakur and Reddy T noted. Politicians friendly to these companies, which are vital to the country’s economy, have written loopholes into liability laws and reduced punishments when they might apply.

Maiden’s facilities have been cited for health violations and shut down over the years, for example, yet the company was allowed to resume operating, wrote researchers in the International Journal of Surgery.

Meanwhile, countries such as Gambia, one of the poorest countries in the world, import most of their medicines from India. It also lacks the legal resources and know-how to fight big multinationals through the courts. Case in point – the parents of the victims hired a US law firm to file suit against the Indian company.

Still, even though the outcome of such a case is likely far in the future, Gambia has already made strides to avert such an occurrence again. Ordinary Gambians feel more empowered to fight for justice, something once unthinkable in the country where more than half of the country lives in poverty. Legislators have taken action to help citizens. And the government is now planning to build a testing facility for imported drugs with support from the World Bank, said Reuters.

The latter is critical: Parents don’t trust Indian-made medicine anymore but have little choice when they or their children are ill and need care. “When I read that a medicine is from India, I barely touch it,” Lamin Danso, whose nine-month-old son died from the cough medicine, told the BBC, which noted that “the reliance on Indian drugs is unlikely to change anytime soon.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $32.95 for an annual subscription, or less than $3 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.