Legislating Legacy

Russian military interrogators tortured Ukrainian soldiers and civilians in a government-owned camp in Belarus, according to a Radio Free Liberty investigation conducted with the Poland-based Belarusian Investigative Center.

“These ‘filtration’ camps cannot be created without authorized government officials who must give their consent to this,” said Yulia Polekhina, a Ukrainian human rights advocate who accused Belarussian President Alexander Lukashenko, an autocrat and ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin, of allowing the Russians to use the state-owned facilities.

“When people are beaten, tortured, and denied medical care, this is a war crime,” Polekhina added. “And this cannot happen without the consent of the authorities.”

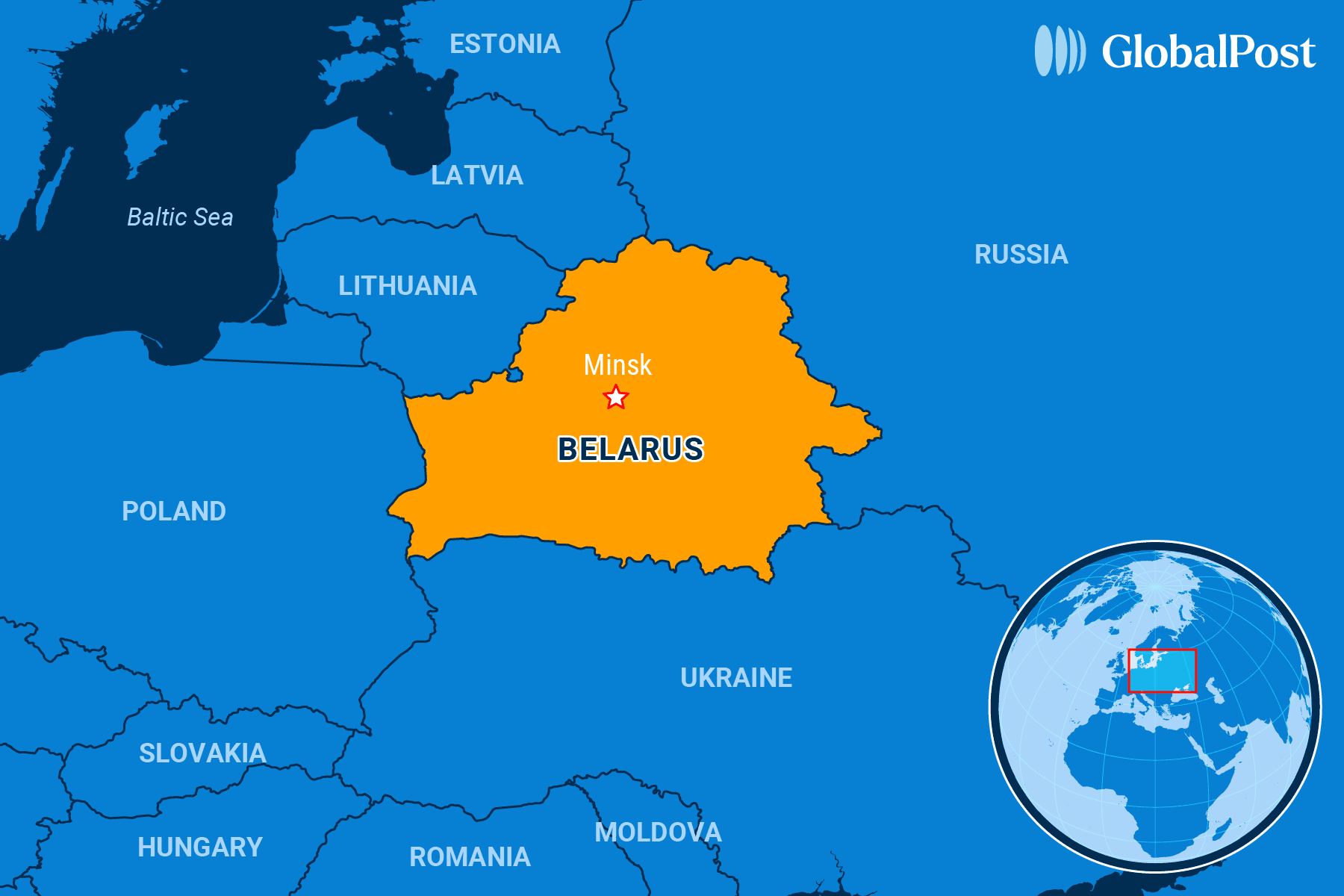

Hundreds of Ukrainians, including children, were cycled through the camp in Naroulia, Belarus, about 40 miles from the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant across the border in nearby Ukraine, wrote the Kyiv Post, citing the investigation. Many were then transported to Russia. Lukashenko’s administration did not comment.

The camp highlights how the former Soviet republic of Belarus is helping Putin to invade and subjugate another former Soviet republic, Ukraine. And those efforts are unlikely to stop anytime soon.

That’s a remarkable about-face for Lukashenko, who a decade ago began making efforts to distance Belarus from Russia and draw closer to the West, mainly to help his country’s economy. But in 2020, he realized he needed Russia too much to maintain power to continue.

That’s because that year, hundreds of thousands of protesters took to the streets after an election that he was accused of rigging to win a sixth term after 26 years in office. Belarusian security forces used rubber bullets, tear gas, flash grenades, and batons to put down the protests. Lukashenko has long denied that any violence occurred.

Now, undergirding Lukashenko’s security state, meanwhile, are even closer ties to the Russian military, including security guarantees that include Russian nuclear deterrence, as the Jamestown Foundation detailed. Russia also provides loans and cheap energy to its former satellite.

At the same time, the Russification of Belarus is steadily on track – the Belarusian language, which like Russian uses the Cyrillic alphabet, is rarely heard on the streets of the capital Minsk and other large cities anymore, wrote the Associated Press. The language of instruction in schools is now Russian. Business and government affairs are also conducted in Russian.

Meanwhile, Lukashenko is now making sure there won’t be a repeat of those protests when the country holds its presidential elections in January. For example, he recently warned that he would shut down the Internet if protesters took to the streets, noted the Kyiv Independent.

Exiled Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who now resides in Canada, told her allies not to flood the streets in January, arguing that they shouldn’t expend energy on a “ritual” preordained to rubberstamp the autocrat, Reuters wrote.

The regime has bred its critics over the years, critics who continue to fight. Belarusians like ex-police officer Viachaslau Hranouski are working to counter Lukashenko and Putin. As the Guardian reported, Hranouski is now fighting the Russians on the front lines for the Ukrainian military to undermine Lukashenko’s most important ally – and by extension, Lukashenko. “The only way to defeat him is to fight Putin,” he said.

However, a recent constitutional change is making any effort to dislodge Lukashenko or his ilk harder.

Earlier this year, Belarus held the inaugural congress of the All-Belarusian People’s Assembly (ABPA), a newly formed constitutional body made up of carefully chosen loyalists, which has unprecedented powers including the ability to overturn decisions made by other state bodies, parliament, and the courts, the European Council on Foreign Relations wrote. They can remove anyone in power, including presidents, lawmakers, and judges, too.

This so-called supreme body is essentially a way for Lukashenko to hold power after he steps down, wrote World Politics Review.

“Shaken by the images of hundreds of thousands of Belarusians calling for his ousting, the embattled Lukashenko told a convening of the assembly in February 2021 that a permanent body would act as a ‘clear safety net so as not to lose the country’ should the ‘wrong people come to power,’” the magazine wrote. But it was also a move that “reassured Belarus’ long-time ally Russia that the country would continue to operate under the Kremlin’s sphere of influence long after the Lukashenko era ends.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $46 for an annual subscription, or less than $4 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.