Irreconcilable Differences

A few years ago, Belgium famously had no elected government for more than 600 days, as politicians negotiated a coalition agreement.

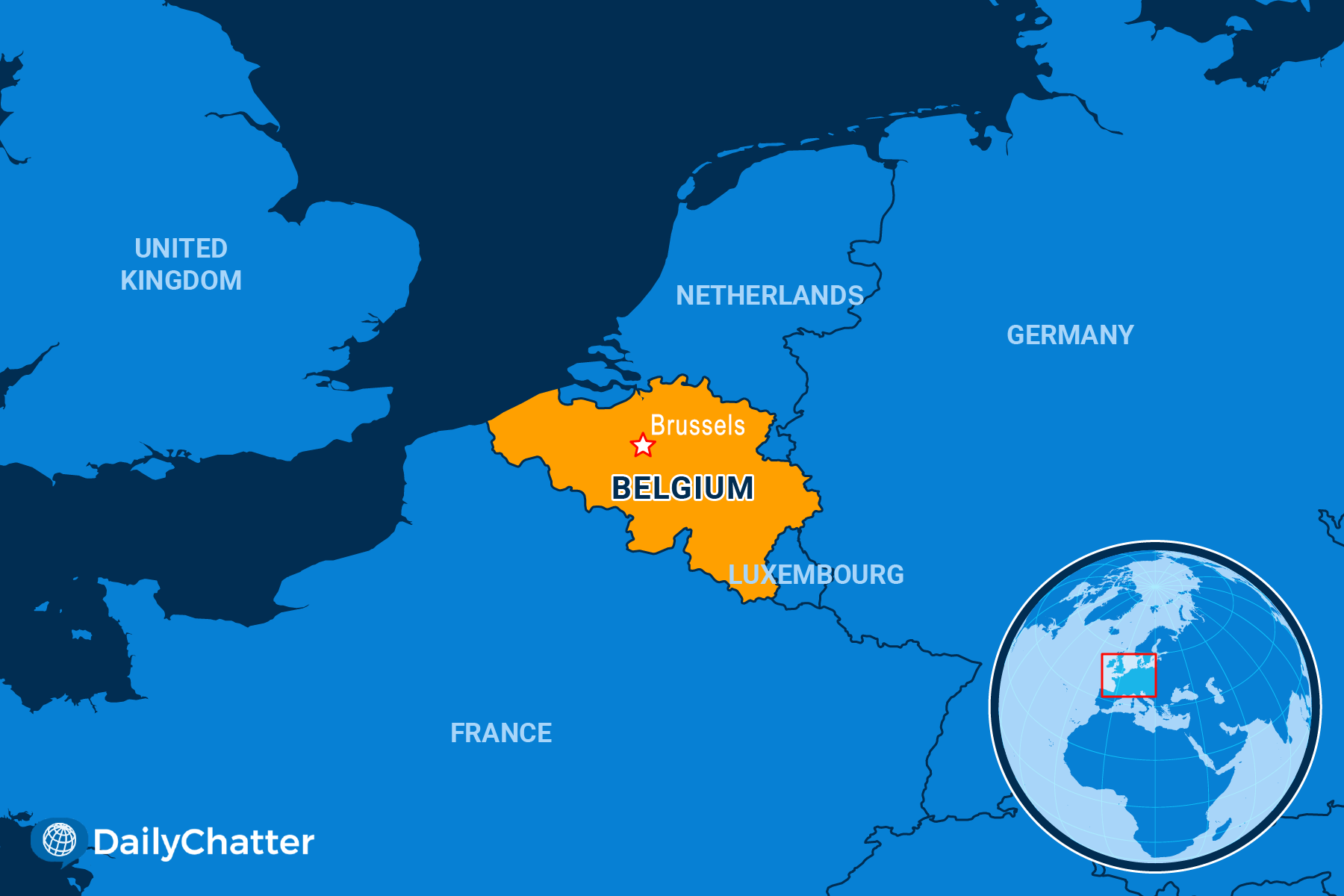

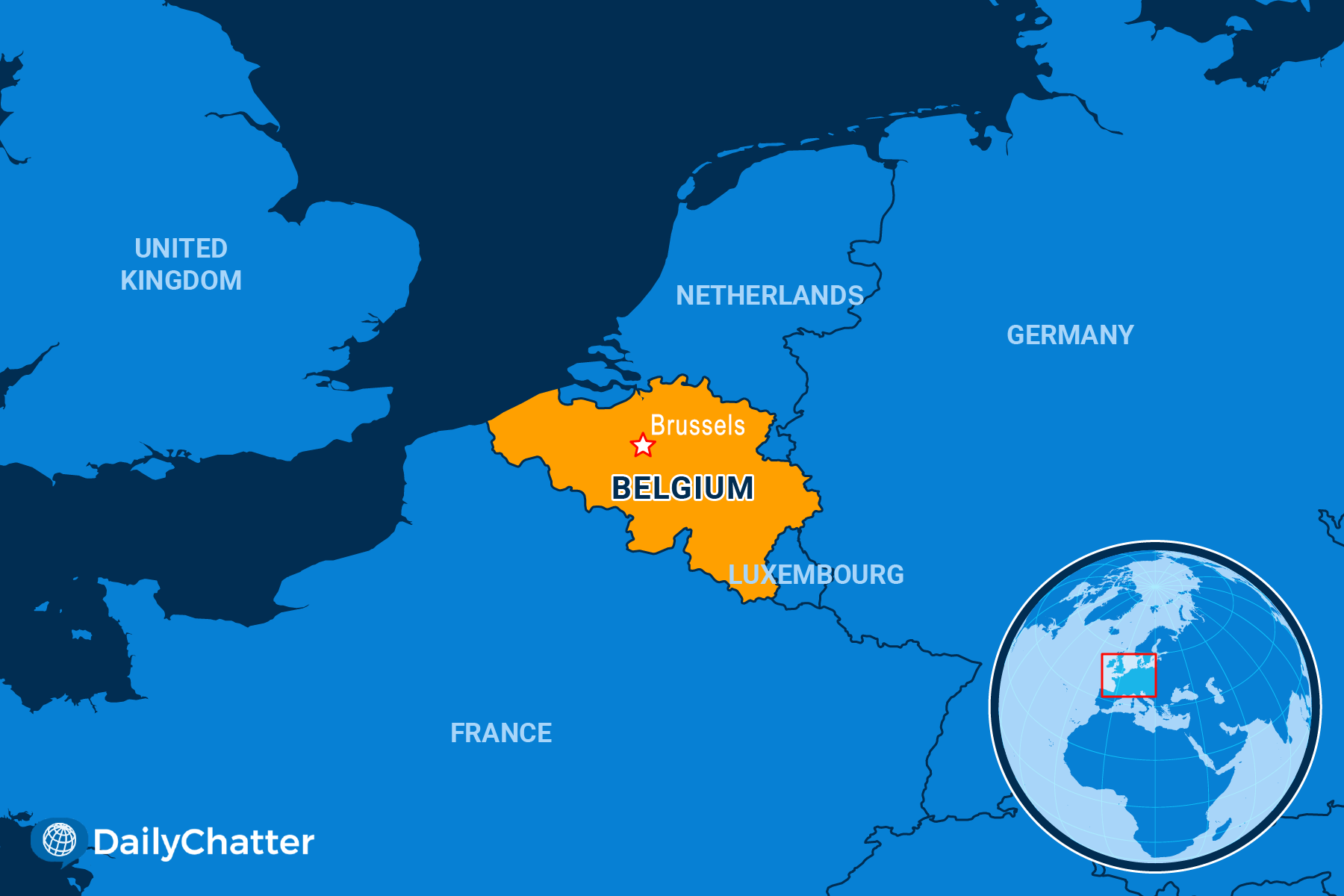

Now, reflecting that history of instability, Belgians are seriously discussing splitting the country into Dutch-speaking Flanders in the north and French-speaking Wallonia in the south.

“We believe Belgium is a forced marriage,” Tom Van Grieken, the leader of the political party Vlaams Belang, told Politico last year. “If one of them wants a divorce, we’ll talk that out as adults … we have to come to an orderly division. If they don’t want to come to the table with us, we’ll do it unilaterally.”

Vlaams Belang is expected to become the largest party in parliament when the West European country holds its general election on June 9, reported the Financial Times.

Many Vlaams Belang supporters complain that wealthy, more populous Flanders subsidizes the less well-off citizens of Wallonia. Critics say hate drives their agenda, however.

Originally known as the Flemish Bloc, the party was dissolved in 2004 when a court ruled that members had violated laws against racism, explained Agence France-Presse. But the party rose again under a new name, with a similar campaign platform of halting immigration, stiffening punishments for convicted criminals and other conservative policies.

The party also espouses a Dutch version of the “Great Replacement” theory that claims non-European migrants, especially Muslims, are set to displace Europeans in their own country, for instance.

Meanwhile, voters in Wallonia and Brussels appear to be heading in the opposite direction. They are expected to back far-left politicians who are likely to clash with Van Grieken and his colleagues, noted the Brussels Times. The Socialists, who are forecast to win the most seats in Wallonia, would tax the wealthy, boost spending, and follow similar leftist policies. The leftist Worker’s Party would push those policies even further along a Marxist bent, added the Rosa Luxembourg Stiftung.

These sharp divisions reflect voters’ lack of confidence in their government and democracy, wrote the Robert Schuman Foundation. Unfortunately, the election could exacerbate those views as gridlock between polar opposite political parties grips Brussels.

Under Belgium’s election system, Flanders, Wallonia, and Brussels elect lawmakers who must then work together to form a federal government. That’s not easy when one of the three wants to eliminate the system altogether. However, the New European envisioned a silver lining to these tensions. Left and centrist parties might unite to stop Vlaams Belang.

It added, nothing brings folks together like a common enemy.

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $32.95 for an annual subscription, or less than $3 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.