Just Say No

Two years ago, officials in British Columbia decriminalized the possession of small amounts of drugs like cocaine, fentanyl, heroin, and methamphetamines to end the stigma that often keeps addicts from seeking help.

“Addiction is a health issue, not a criminal one,” wrote the western Canadian province’s website. “Decriminalizing people who use drugs is one of the many actions B.C. is taking to respond to the toxic drug crisis that is killing our loved ones, so people live to get the care they need – from prevention and harm reduction to treatment and recovery.”

The problem was, more drug users started shooting up, smoking, nodding off, and sometimes perishing in parks, on beaches and on public transportation. A record 2,511 drug deaths occurred in British Columbia last year, reported the New York Times, noting that overdoses claimed more lives of individuals between the ages of 10 and 59 than homicides, suicides, accidents, and natural causes. More than 42,000 have died for similar reasons since 2016.

Folks had enough. Last month, officials in the province recriminalized hard drugs, banning people from using in public spaces, the BBC reported. Possessing small amounts of hard drugs is still legal, but use must occur in residences, clinical settings and other safe spaces.

Politics played a big role in the shift. The center-left New Democratic Party that runs British Columbia championed the soft-on-drugs policy. In the run-up to provincial elections in November, however, the Conservative Party has gained in the polls after they pledged to adopt nearby Alberta’s “recovery-oriented approach,” which aims to help users overcome their addiction rather than reduce the harm their habits might cause, according to the Washington Post.

Still, opioid-related deaths in Alberta have increased significantly over the past year, according to Health Canada. And the rate of opioid deaths per 100,000 people through the first 10 months of 2023 in Alberta was only slightly below the rate in British Columbia.

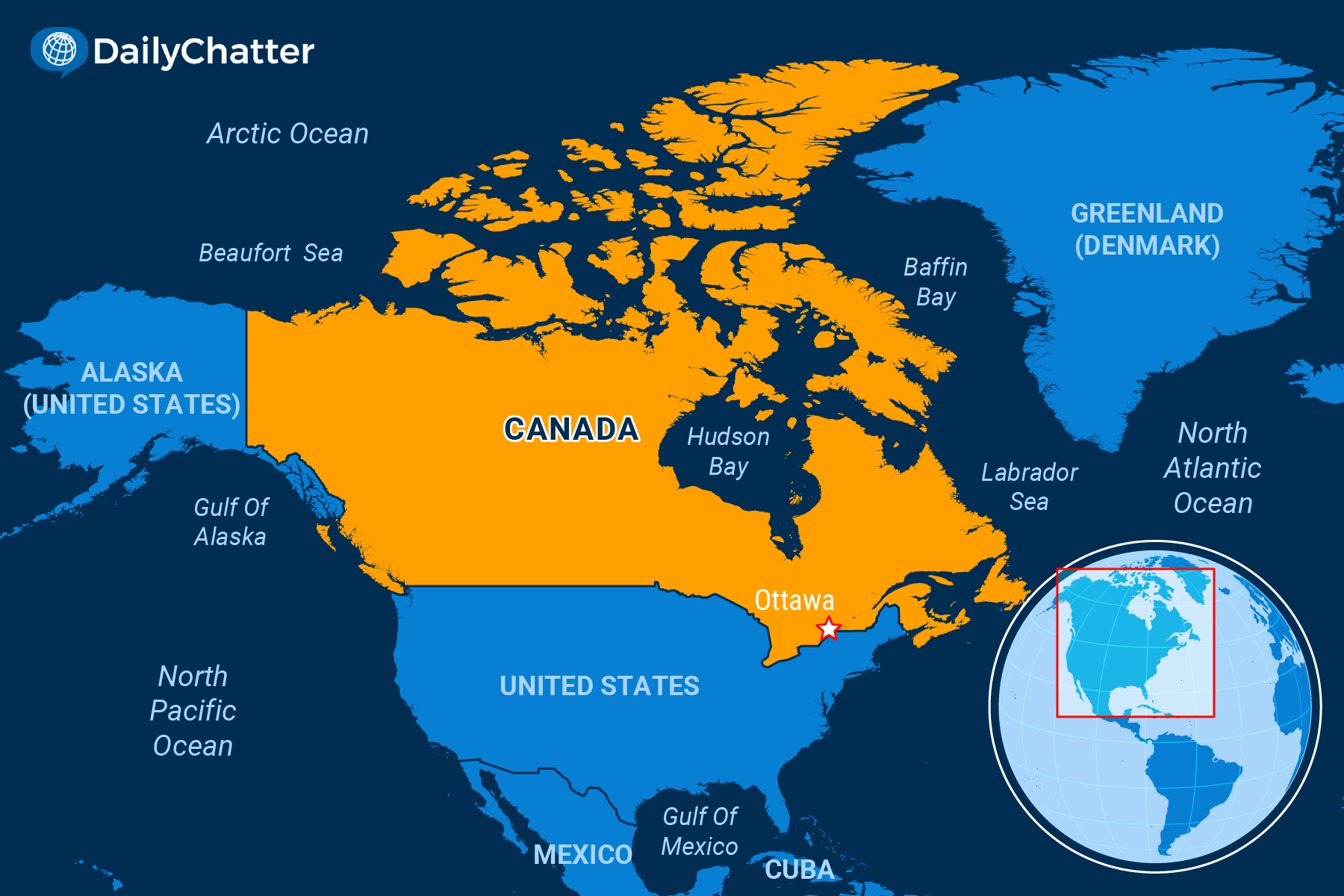

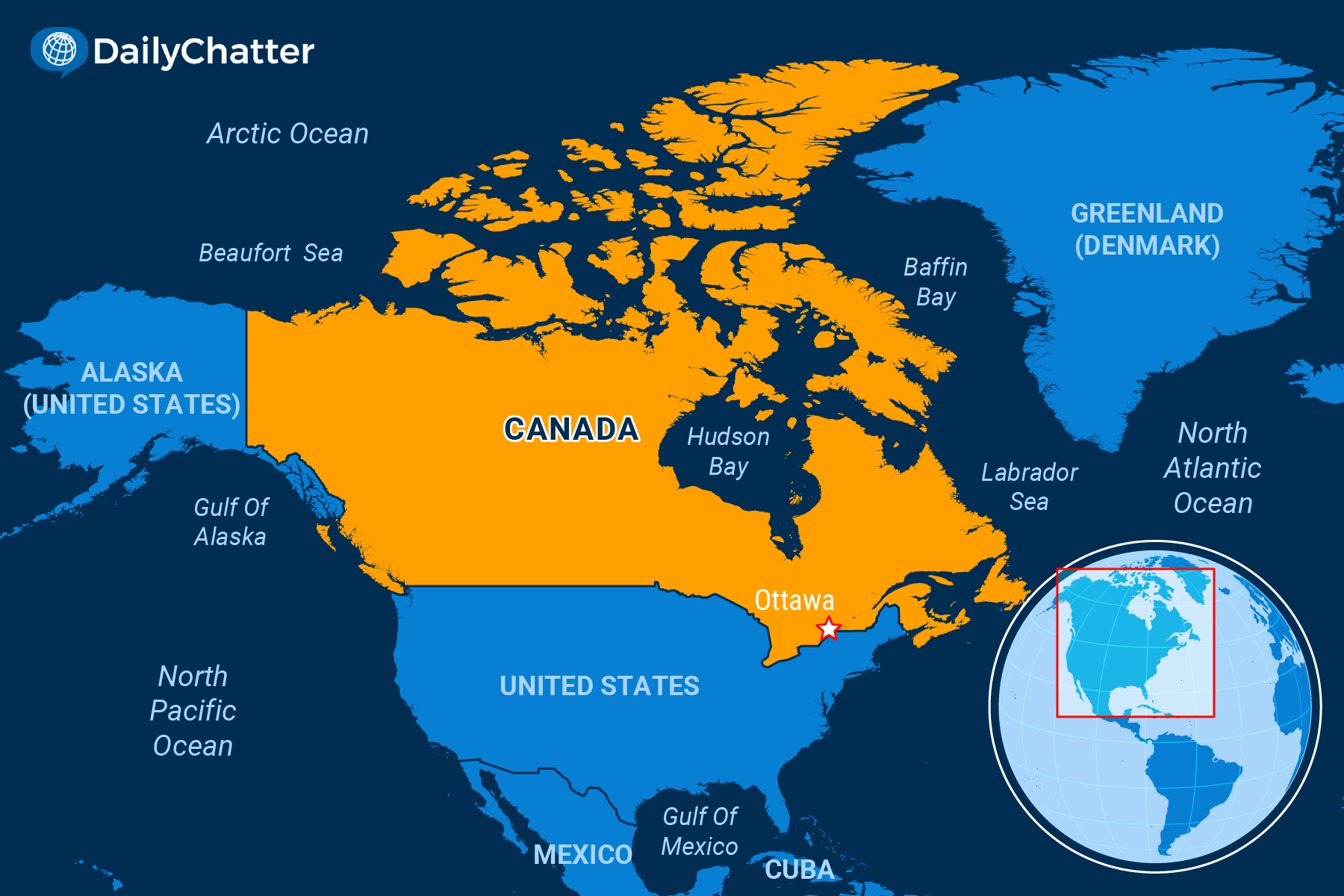

Meanwhile, the concerns over the soft-on-drugs policy are echoing in the federal capital of Ottawa, too. Officials in Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberal Party recently rejected Toronto’s request to decriminalize drugs, the BBC noted, citing public safety and the unpopularity of the request.

Before that decision, Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre blasted Trudeau for even considering Toronto’s request, reported Canada’s Global News. Ontario Premier Doug Ford, a conservative, opposed the move, too, the Toronto Sun added, saying he didn’t want a drug epidemic to explode in his province.

In another potential sign of the shift in attitude, law enforcement in British Columbia recently charged two drug decriminalization advocates with trafficking after they said they would give pure cocaine, methamphetamine and heroin to addicts in a “compassion club,” added the Guardian.

Unfortunately, these developments don’t get at the heart of the problem, a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation analysis found, noting that whether or not illicit drug use is criminalized, people keep turning to these risky substances.

“One conclusion to be drawn … might be that the scourge of opioid addiction continues to defy simple answers,” the broadcaster wrote. “But all such nuance is in danger of being drowned out by the shouting.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $32.95 for an annual subscription, or less than $3 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.