The Last, Wobbly Domino

When polls in the landlocked central African country of Chad open on May 6, it will be the first of coup-hit states across Central and West Africa to use the ballot box to try to emerge from years of military rule.

But no one really believes that will actually happen, reported France24. Instead, what’s more likely is the vote provides a veneer of legitimacy to the military-run government led by a man whose hold on power is shaky.

In the race, Gen. Mahamat Idriss Déby Itno, whom the military junta installed in power three years ago after the death of his father, will face off against a host of opposition candidates – including Prime Minister Succès Masra, a former rival of the general who became premier four months ago in a power-sharing agreement that Déby blessed, reported the Senegal-based African Press Agency.

Critics don’t think Masra is really interested in becoming president, they think he is running to split the vote. “The opposition says his candidacy is a ploy to give an appearance of pluralism in a vote the junta chief is certain to win with his main rivals (either) dead or in exile,” wrote Le Monde.

Since gaining independence from France in 1960, Chad has not realized a peaceful, orderly or fair transition of power. Instead, coups d’état and rebellions mark its history. Déby’s father, Idriss Déby, was a violent autocratic who was killed while fighting rebels after 30 years in power, wrote the Guardian. His generals elevated his son to lead them. Now, lacking his father’s military record – though trained at a French military academy – he’s seeking to secure his legitimacy through an election.

His apparent means of winning, however, includes shutting down talk shows, deploying security forces who fire upon protesters, and competing against rivals who conveniently fall victim to murder, prosecutions and other career-ending happenstance, civil society advocates say. He has also partnered with France, the latter as a security guarantor, at a time when Russian forces have gained ground in the formerly French colonies in the region and kicked French forces out (as in Mali, for example), added World Politics Review.

With this context in mind, some Chadian observers wonder aloud if Masra is truly running to defeat Déby. Masra has hit the campaign trail, where crowds assembled for his events. University of N’Djamena political scientist Kelma Manatouma told Agence France-Presse that Masra now believes he might replicate in Chad the surprise victory of Diomaye Faye, who won Senegal’s presidential election in March.

At the same time, Déby is angering the generals in control, not least because he’s solicited Hungarian military help, ostensibly to avoid a coup deposing him. Even so, rumors of coups are rife in Chad these days.

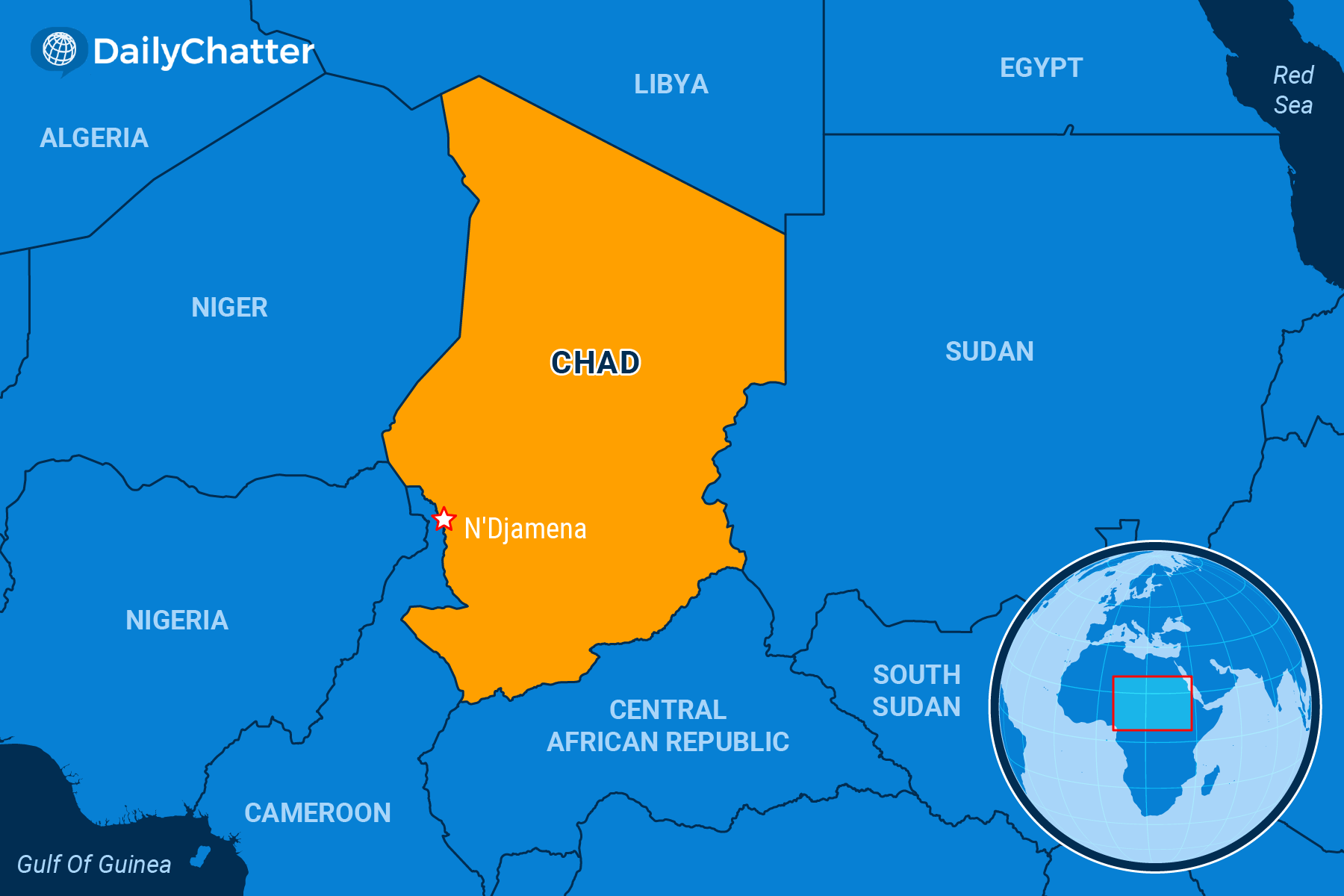

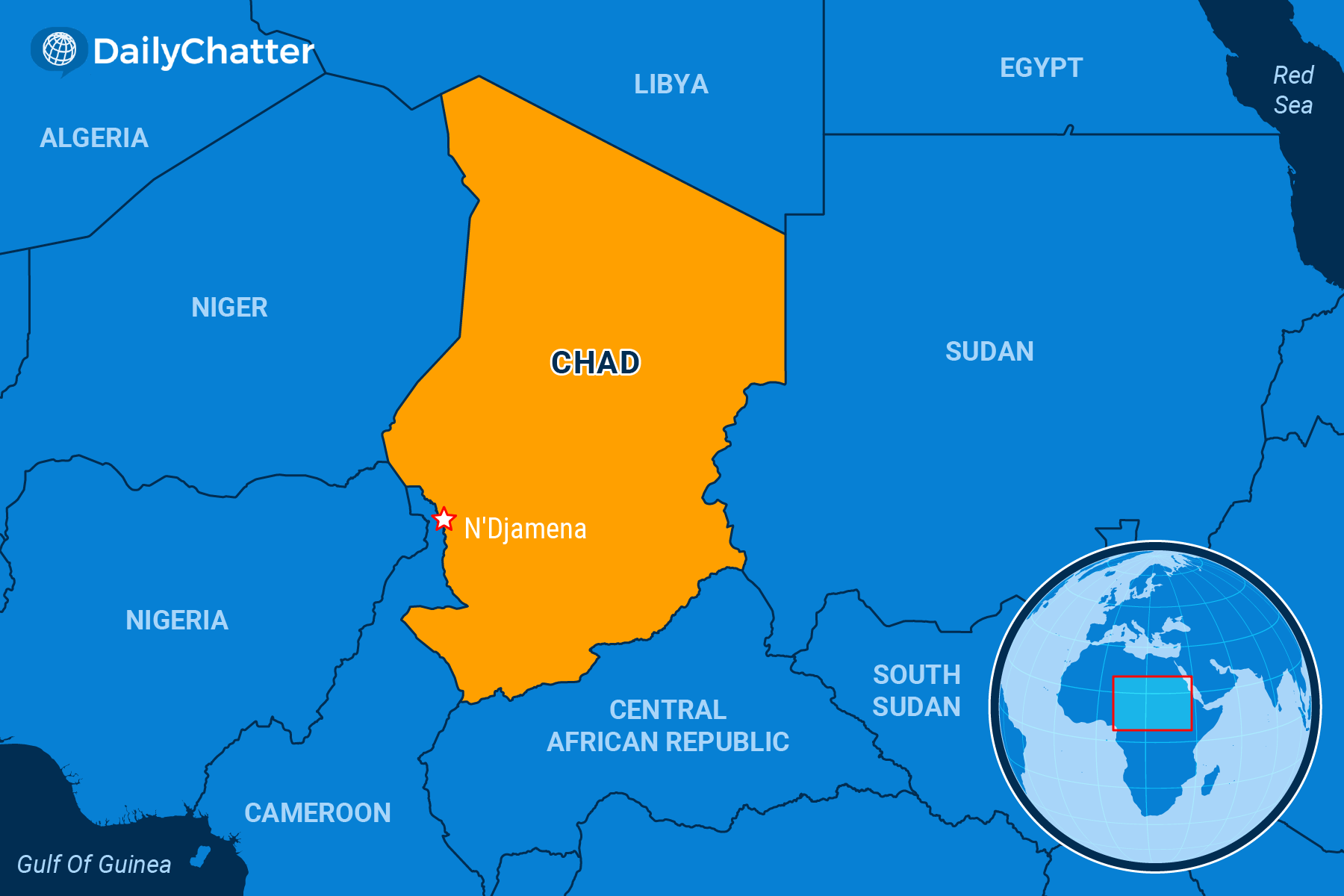

Chad’s politics are important because Chad sits at the crossroads of Africa. It borders Libya, Sudan, the Central African Republic, Cameroon, Nigeria, and Niger – all hot spots where terrorism, civil wars, internecine violence, refugee migration, crimes against humanity, and state and societal breakdowns have been ongoing for decades, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies. It calls the region the “most dangerous and unstable stretch of territory in the world today.”

The problem is, say analysts, that its geographical location – between a raging civil war to the east in Sudan and an unchecked terrorist insurgency in the western Sahel – means that Chad’s collapse could be a disaster. It would create a bridge that merges “the flow of fighters, weapons, and violence between these two regions” embroiled in conflict, “a virtual Pandora’s box clear across Africa.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $32.95 for an annual subscription, or less than $3 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.