Handshakes and Bombs

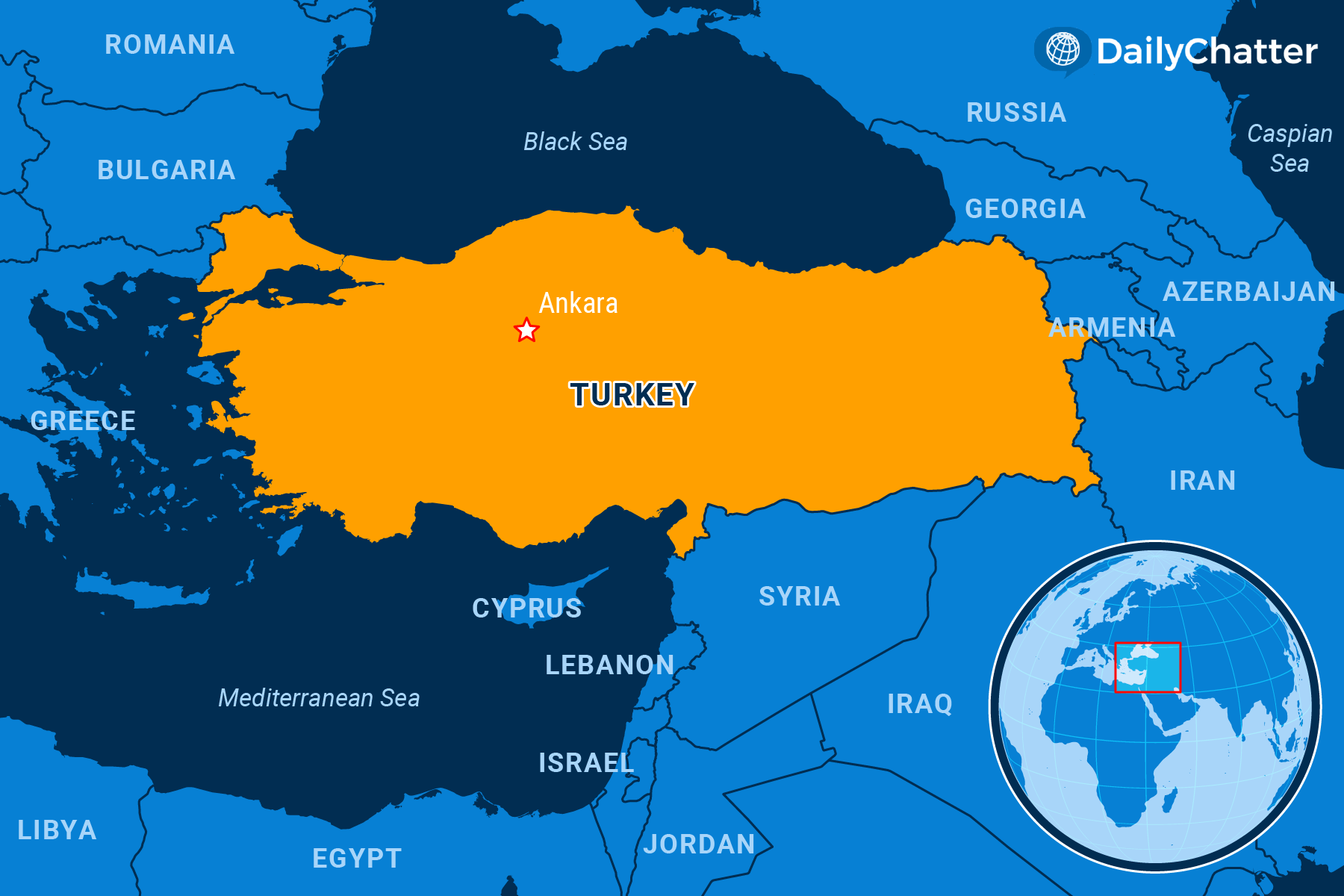

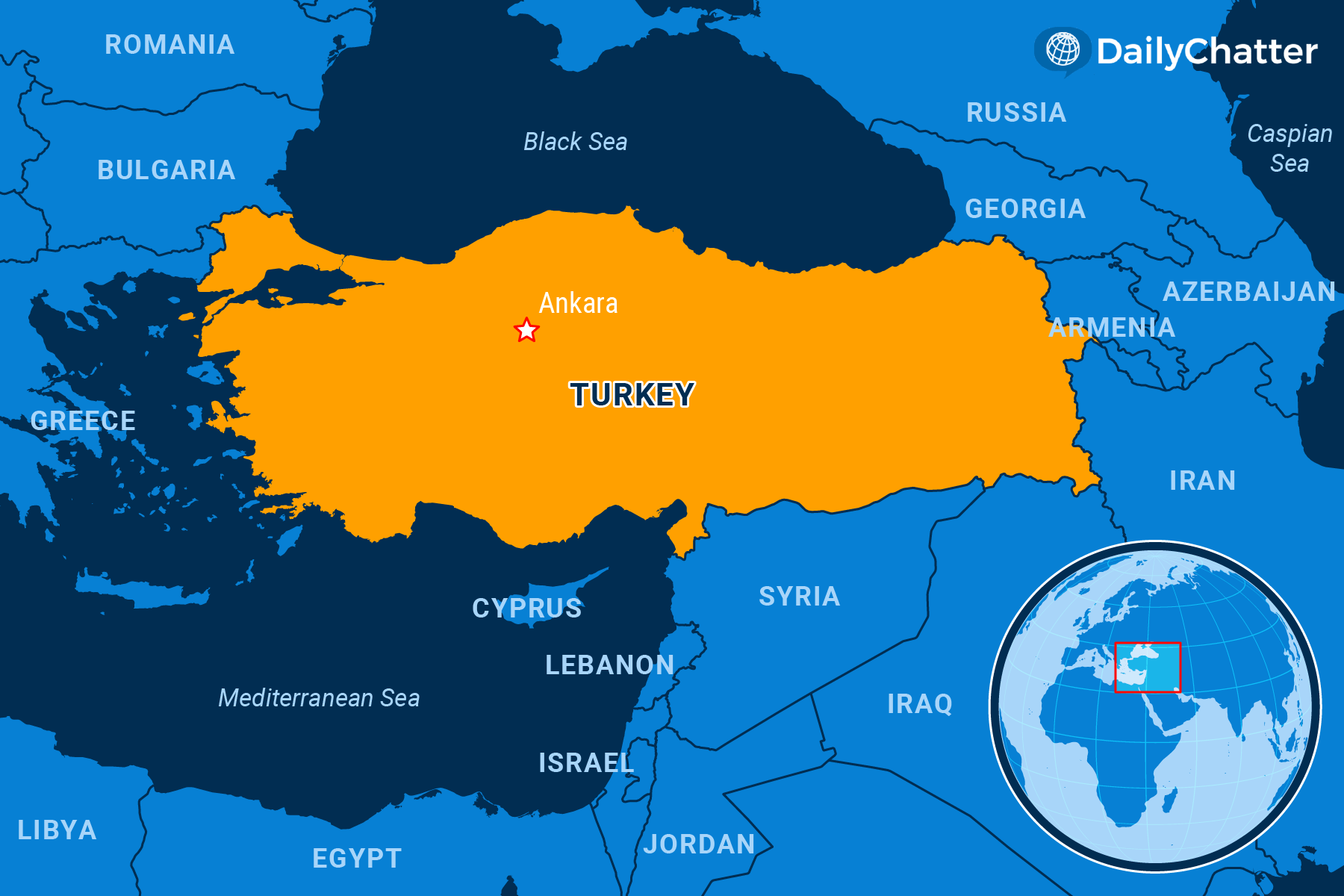

In mid-November, a 23-year-old Kurdish woman from Syria planted a TNT-laden bomb in a flower bed on Istiklal Avenue, the lively Istanbul commercial thoroughfare that draws even more crowds than the renowned Grand Bazaar.

The resulting explosion claimed six lives and injured more than 80 bystanders.

Within days, police charged the alleged bomber, Ahlam Albashir, and more than a dozen other suspects with murder and “attempts against the unity of the state,” while acting on behalf of the separatist Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) as well as affiliated Syrian-Kurdish groups.

In the aftermath, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan ordered retaliatory airstrikes on Kurdish strongholds in northern Syria and Iraq, calling it Operation Claw Sword. Some of the missiles that Ankara launched carried the names of Turkish victims.

This opening salvo of an offensive that is to include the invasion of Kurdish-held areas in Syria drew objections from the United States: It was concerned about the safety of US troops stationed nearby – but the US is also stuck in the conflicted position of partnering with Turkey in the NATO alliance while supporting Kurdish forces in the fight against Islamic State.

But the big bombshell falling alongside these events, say analysts, is Turkey’s about-face on Syria: Frustrated with his inability to elicit an American endorsement for his war against Kurdish nationalists, the Turkish leader is now seeking to mend relations with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad – a reversal of a decade-long policy to see the Syrian leader removed.

“If relations have improved with Egypt, the same thing may happen with Syria,” said Erdogan, referring to his rapprochement with leaders he previously shunned, for example, shaking hands with Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi recently at the World Cup in Doha. “In politics, there is no such thing as not speaking to each other.”

These moves will likely result in the withdrawal of support for the Syrian opposition from its most trusted ally since the war broke out more than a decade ago, say insiders. Most interviewed for this article wouldn’t go on the record to confirm such a move – but they admitted it’s coming.

Other diplomatic moves point in that direction, too. At a meeting earlier this month with Russian President Vladimir Putin, Erdogan proposed three-sided negotiations on “deconfliction measures” that would include Turkish, Russian, and Syrian officials considering security agreements and restoring Turkish-Syrian ties.

“Until recently, Turkey was concerned with who controlled Syria, and it was against Assad,” wrote Omer Onhon, a former Turkish Ambassador to Syria, in an analysis for the Saudi daily Asharq Al-Awsat. “Now, what concerns Turkey most, seems to be Syria’s territorial integrity rather than who controls it.”

The shifting alliances come amid a dire economic situation in Turkey, which is experiencing 170 percent inflation, rising unemployment, and the daily devaluation of the Turkish lira.

Meanwhile, public support in Turkey for invading Kurdish-held territory in Syria is high, especially following the terror attack in Istanbul.

Alongside that, many Turks blame the 3.6 million Syrian refugees for the nation’s problems, polls show: For example, more than 60 percent of Turks in Istanbul – which has served as a hub for the aspiring Syrian government-in-exile for more than a decade – say the country has a refugee problem.

And in 2023, Erdogan is up for re-election.

“It’s all about the June elections,” a prominent Syrian opposition leader told DailyChatter. “The days of solidarity with the displaced victims are over. Erdogan knows the street blames Syrians for Turkey’s economic problems. And (Syrian) activists are being told by Turkish authorities to tone down their criticism of al-Assad.”

That resentment of refugees has already resulted in growing support for Erdogan’s opponents. For example, Republican People’s Party chairperson Kemal Kilicdaroglu had already pledged to re-establish diplomatic ties with the Assad regime years before the current administration’s overtures.

Meanwhile, Turkey will need Syrian cooperation if it wants to move forward with a plan to relocate thousands of refugees to a “safe zone” 20 miles inside Syria, where Interior Minister Suleyman Soylu said 75,000 houses had been constructed over the past two years to house them.

A Russian-facilitated Erdogan-Assad handshake is a bitter pill for the battered Syrian opposition, which had been holding its own in its fight against the Assad government until Russia got involved militarily on the government’s side a few years ago.

At the same time, food shipments and medical help for the remaining rebel-held enclave in northwest Syria pass through Turkish territory, as do the arms the opposition needs to stay in play.

Still, losing support from Turkey means more than just the loss of a political ally or a corridor for goods. It’s the opposition’s loss of a home, and maybe its future.

“We’ve been urging (opposition) headquarters to move out of Istanbul,” the Syrian opposition leader said. “But it’s not like there is another country bordering Syria where we’re going to be welcome.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $32.95 for an annual subscription, or less than $3 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.