In Morocco, Gen Z Protesters Want Services, Not Stadiums

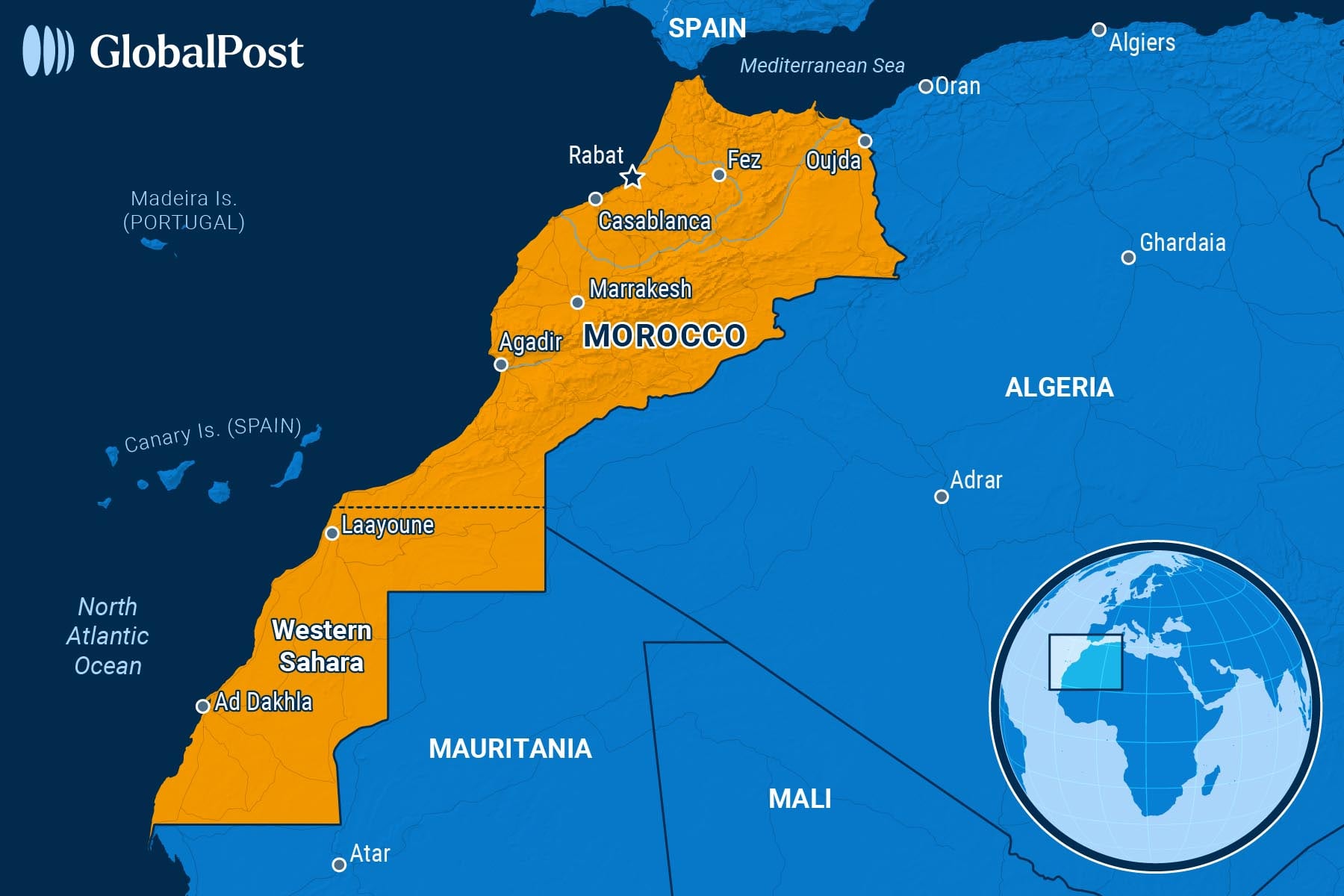

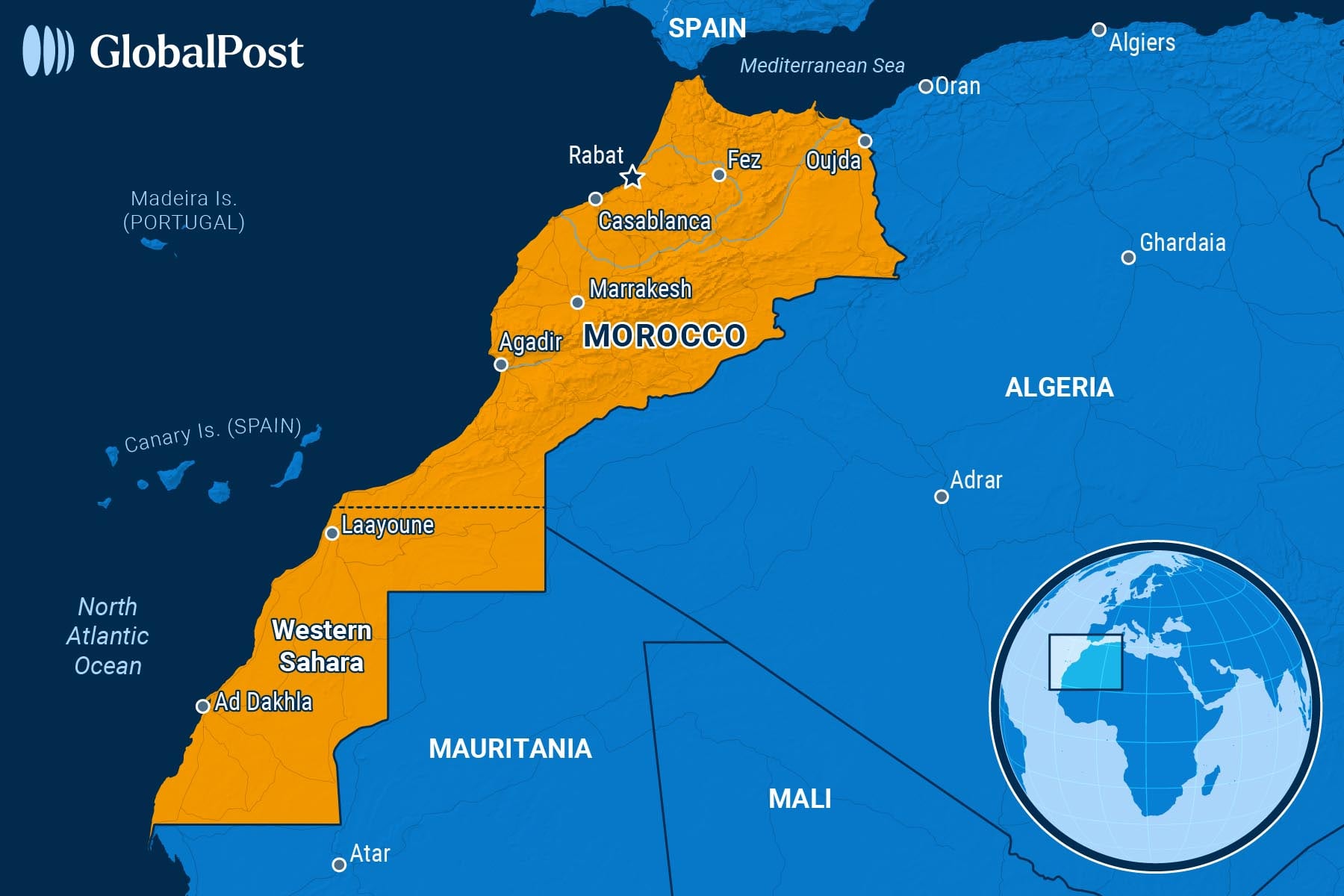

In August, eight women died during routine cesarean sections at Hassan II Hospital in Agadir, in southwestern Morocco.

Two weeks later, thousands of young Moroccans flooded the streets, part of a leaderless movement known as Gen Z 212, demanding that the government explain why it could pour $16 billion into World Cup soccer stadiums while public hospitals can’t keep mothers alive.

“Stadiums are here, but where are the hospitals?” protesters chanted at one demonstration in late September.

The ongoing unrest began outside Agadir’s crumbling Hassan II Hospital, which opened in 1967 and has never been modernized. Instead, it has become a national symbol of Morocco’s “two-speed” system – one in which public health care is collapsing as private clinics thrive.

“We’re short of everything at Hassan II Hospital – medical staff, beds, functioning equipment – but above all, we lack political will,” Saana Faouzi, a physician and opposition figure in Agadir, told Le Monde.

Down the road, cranes rise over a gleaming new university hospital beside a World Cup stadium – a scene, say commentators, that underscores the protesters’ chant: “Fewer stadiums, more hospitals.”

Morocco counts just 7.7 doctors per 10,000 people, with some regions reporting as few as 4.4 –far below the World Health Organization’s benchmark of 25. Across the country, 453 private clinics operate alongside just 166 public hospitals to serve about 38 million people.

In 2024, thousands of medical students and recent graduates protested for months, highlighting a problem that reflects decades of underinvestment and will require years of spending and systematic reforms to improve the way care is financed and delivered, wrote the Middle East Institute.

Meanwhile, the Gen Z 212 group also wants the government to invest more in the crumbling education system: Rural areas lack sufficient school infrastructure, and schools around the country have teacher shortages. Meanwhile, those in the profession routinely protest inadequate compensation: Over the past two years, 30 percent of the teaching force was on strike, affecting schools for months.

And the demonstrators are demanding more effective job creation: Youth unemployment hovers near 36 percent.

Analysts say the country exists in a disjointed reality, where the government prioritizes large-scale infrastructure and leisure projects to promote the country abroad and lure tourists at the expense of investing in serving its citizens. For example, Morocco is eleventh in the world on the FIFA soccer ranking, yet ranks 120th out of 193 countries in the United Nations’ 2025 Human Development Index. It is building the largest stadium in the world in anticipation of hosting the 2030 World Cup, yet it still sits in the bottom half globally of the Healthcare Index score.

While largely peaceful, the protests in several cities have morphed into rioting and destruction of public and private property. At the same time, a crackdown by security officials has led to three deaths. The viral videos of police beating protesters, more than 500 arrests, and an incident on Sept. 30 in which police vehicles drove into crowds in Oujda in eastern Morocco have only inspired more to join the group and protest.

Prime Minister Aziz Akhannouch has offered to speak with the protesters and, in early October, said he would implement reforms to address the protesters’ complaints. The problem is, there is no centralized leadership – the Gen Z 212 coordinates themselves on Discord, TikTok, and Instagram, and have no designated negotiator to speak with.

“This is a decentralized, leaderless and fluid organization, or let’s say, network,” Mohammed Masbah, director of the Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis, told Al Jazeera. “They don’t have any leader and are not affiliated with any political party or union. That makes it difficult for authorities to negotiate or co-opt them because they don’t know who they are.”

Some demonstrators have appealed directly to the king, Mohammed VI. They are not challenging the monarchy, which is revered in Morocco, but asking him to dismiss the Akhannouch government coalition, led by a group of oligarchs and technocrats.

But constitutional reforms championed by the king in 2011 during the Arab Spring protests in the country that redistributed power from palace to parliament now limit his ability to dismiss the government or intervene directly.

Even so, on October 10, King Mohammed VI addressed Parliament for the first time since the protests began, urging his government to accelerate development programs and bridge the divide between Morocco’s megaprojects and its collapsing public services. He called for “a faster pace and stronger impact” from reforms.

Akhannouch, one of the world’s richest men, will likely remain in office, and Morocco’s political establishment is holding its line, say analysts. With parliamentary elections not until September 2026, Akhannouch can afford to wait. Morocco’s elites have weathered past unrest through symbolic gestures while keeping the system intact.

But that doesn’t mean the protesters are going to stop anytime soon. They are taking inspiration from other youth-led protests that have brought down governments in recent years in Nepal and Bangladesh, and are threatening others around the world.

“Beneath the spectacle of gleaming stadiums and bullet trains lies a deeper hunger for dignity, accountability, and equity,” wrote Sarah Zaaimi of the Atlantic Council. “Gen Z Moroccans are charting their own course toward justice…their quest is not against the crown or the system, but against the illusion that performance equals progress. Whether the (the establishment) chooses to listen – or continues dazzling itself with its own reflection – will define the trajectory of an entire nation.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $46 for an annual subscription, or less than $4 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.