In The Ceasefire Between Rwanda And The DRC, Peace Is An Afterthought

There was much fanfare after a peace agreement was signed in late June to end decades of warfare between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Officials such as US President Donald Trump hailed the US-brokered agreement as a big step in finally stopping a brutal conflict that has killed thousands and displaced millions just this year.

“Today, the violence and destruction comes to an end, and the entire region begins a new chapter of hope and opportunity, harmony, prosperity and peace,” Trump told the foreign ministers of the two countries at the White House signing, calling the agreement the “Washington Accord.”

But despite the ceremonies and the plaudits, many observers just shake their heads, saying the peace won’t hold because it wasn’t the main aim in the first place.

“While Trump has all but proclaimed a historic peace, worthy in his mind of the Nobel Peace Prize he covets, the war has raged on, deepening a humanitarian catastrophe worsened by the impact of US funding cuts to international aid,” wrote World Politics Review. “These contradictions have fueled skepticism among observers about whether these diplomatic breakthroughs will deliver on the ambitious promises made to the people of the region, or whether they are simply politically expedient transactional exchanges based on narrow security and economic interests.”

In this deal, the DRC and Rwanda have agreed to respect each other’s territorial integrity and cease hostilities, while the agreement also paves the way for greater US investment in the DRC’s critical minerals.

Another agreement, negotiated by Qatar in July, was signed by the DRC and the M23 militia, the Rwanda-backed rebel group that invaded parts of eastern DRC earlier this year.

It pledges to end the fighting in the eastern DRC but doesn’t address Rwandan and M23 withdrawals from that region or when Congolese authority over the captured territory will resume. It does, however, set a date for negotiations for a peace agreement – Aug. 8 – and a deadline 10 days later to finalize a deal.

The problem is that both agreements do little to address the root causes of the conflict, omissions that some say will preclude a lasting peace. Others, however, are more optimistic, adding that they promote long-term stability in the region.

The fighting between the two countries has its roots in the Rwandan genocide in 1994. After it ended, some of those responsible fled to the DRC to escape retribution from troops led by Paul Kagame, who led a rebel army in the 1990s and has been president of Rwanda since 2000.

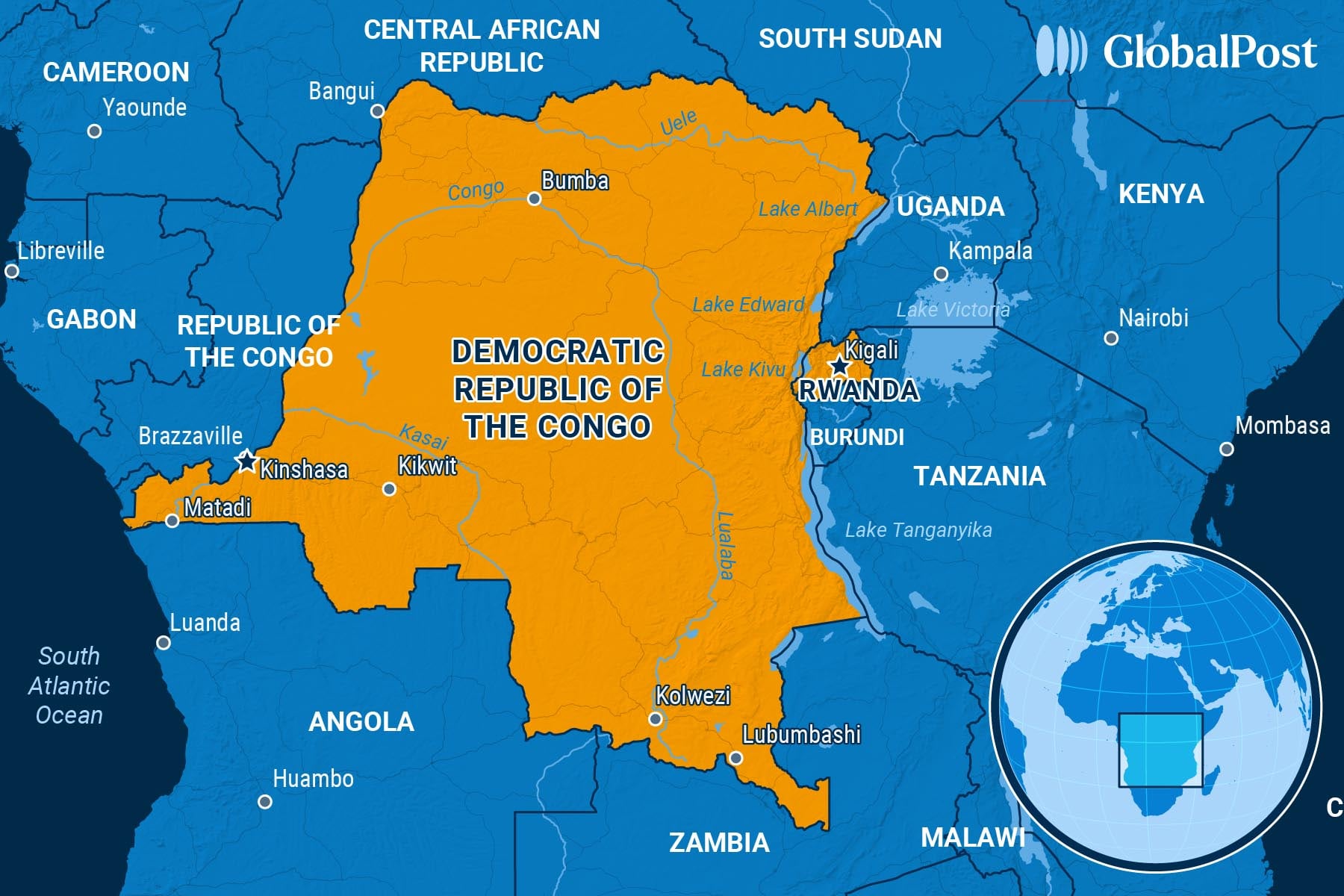

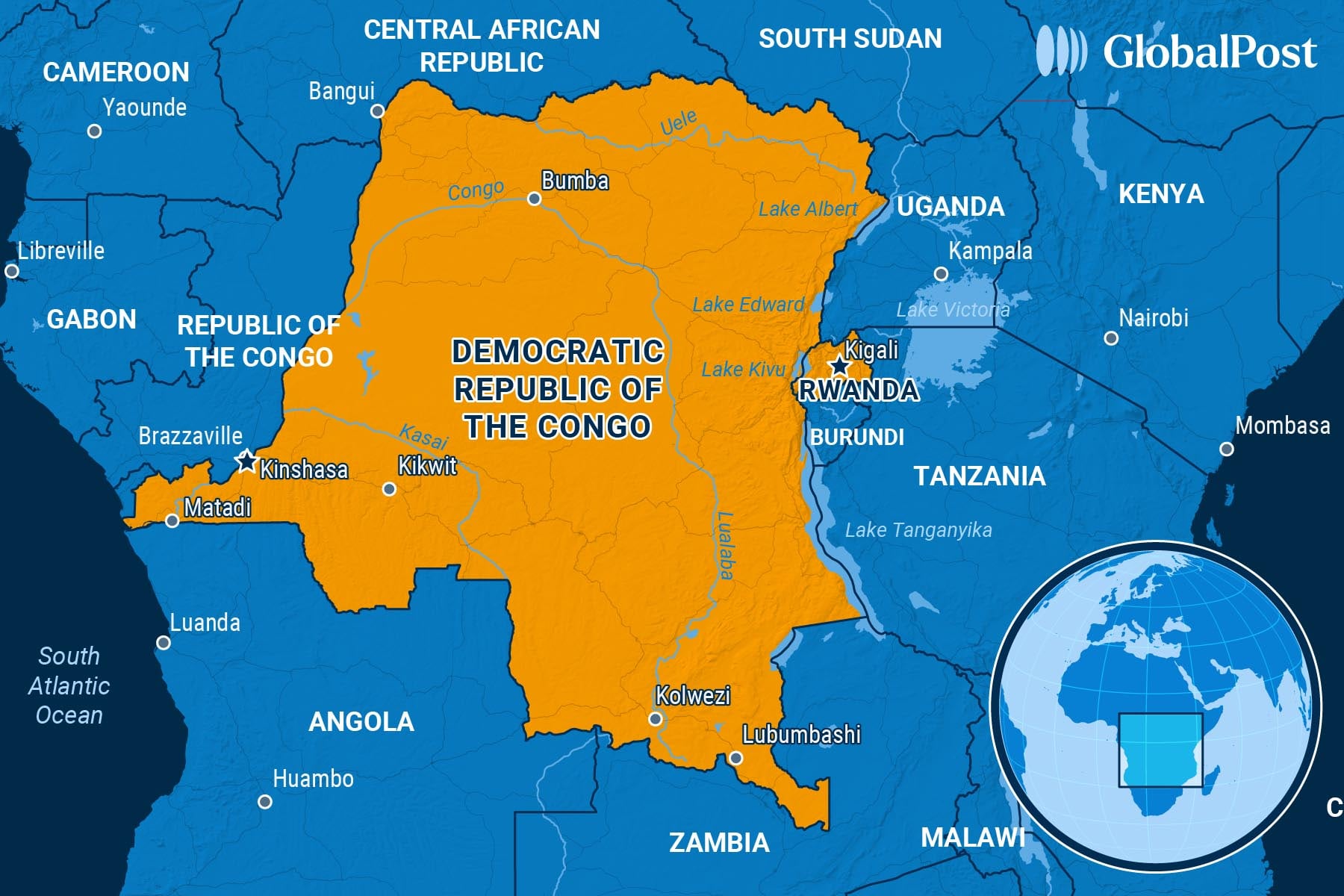

Since then, Rwanda has periodically invaded the DRC – either directly or through its proxies – it says to capture those former Rwandan soldiers, some of whom formed the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR). Those attempts have led to two regional wars that killed millions of people in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The fighting, however, continues to this day, now involving more than 120 militias and armed groups active in the eastern provinces of the DRC – some are aligned with Rwanda or the Congolese army, while others fight Burundi or Uganda, or are affiliated with Islamic State.

During the most recent flare-up that began in January, the M23 militia, backed by Rwanda, marched into the eastern region and captured territory that included the regional centers of Goma and Bukavu. M23’s brutal advance, which killed 7,000 people and displaced millions, threatened to blow up into another regional war, drawing in Burundi, Uganda, and South Africa.

That’s part of the problem with the peace agreements now, say observers. They fail to involve other regional players in a conflict that is broader than just the DRC or Rwanda.

Another issue is that it is based on narrow interests beyond peace, say analysts. For example, the US wants to displace China, which dominates the mineral-rich country’s mining sector and open the door for its investors. Qatar is looking out for its existing investments in Rwanda and the DRC. Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi, who as per the agreement has promised to disband the FDLR, wants to stay in power and keep his country together.

Meanwhile, Rwanda and its M23 partners, which hold the cards, have no interest in leaving the eastern part of the Congo without the threat of harsh sanctions or a steep payoff, say observers, adding that such a carrot-and-stick approach may not be enough to offset the territorial ambitions of Rwanda and the riches they covet from the region.

In the DRC, meanwhile, locals speak about the peace deals as if they have heard it all before.

“People are tired,” one resident of Goma told the BBC. “They are not interested in talks. All they want is peace.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $46 for an annual subscription, or less than $4 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.