Bridging a Divide

A bridge over the Ibar River divides the Kosovan city of Mitrovica between the north and the south, and between the Serb and Albanian communities.

A microcosm of the small, tense, and divided Balkan country of two million, the bridge has been mostly closed for more than a decade, often barricaded by the Serb community with burned-out trucks and other detritus to ensure the two sides stay apart.

However, it’s been Kosovo’s prime minister’s mission to make the country whole. Last year, when Albin Kurti tried to reopen it, however, Kosovo’s Serbian community protested, saying that it shields them from “ethnic cleansing.”

But Kurti says opening the bridge is about normalization: “Kosovo is a normal state and its bridges should be normal, too, which means open.”

Still, Serbia opposed it. Western countries did, too, worried about further escalating tensions that have already been simmering between the two communities over the past few years.

Now, as Kosovo’s voters go to the polls on Feb. 9 to choose their lawmakers, the elections have become a proxy for the conflict in the country.

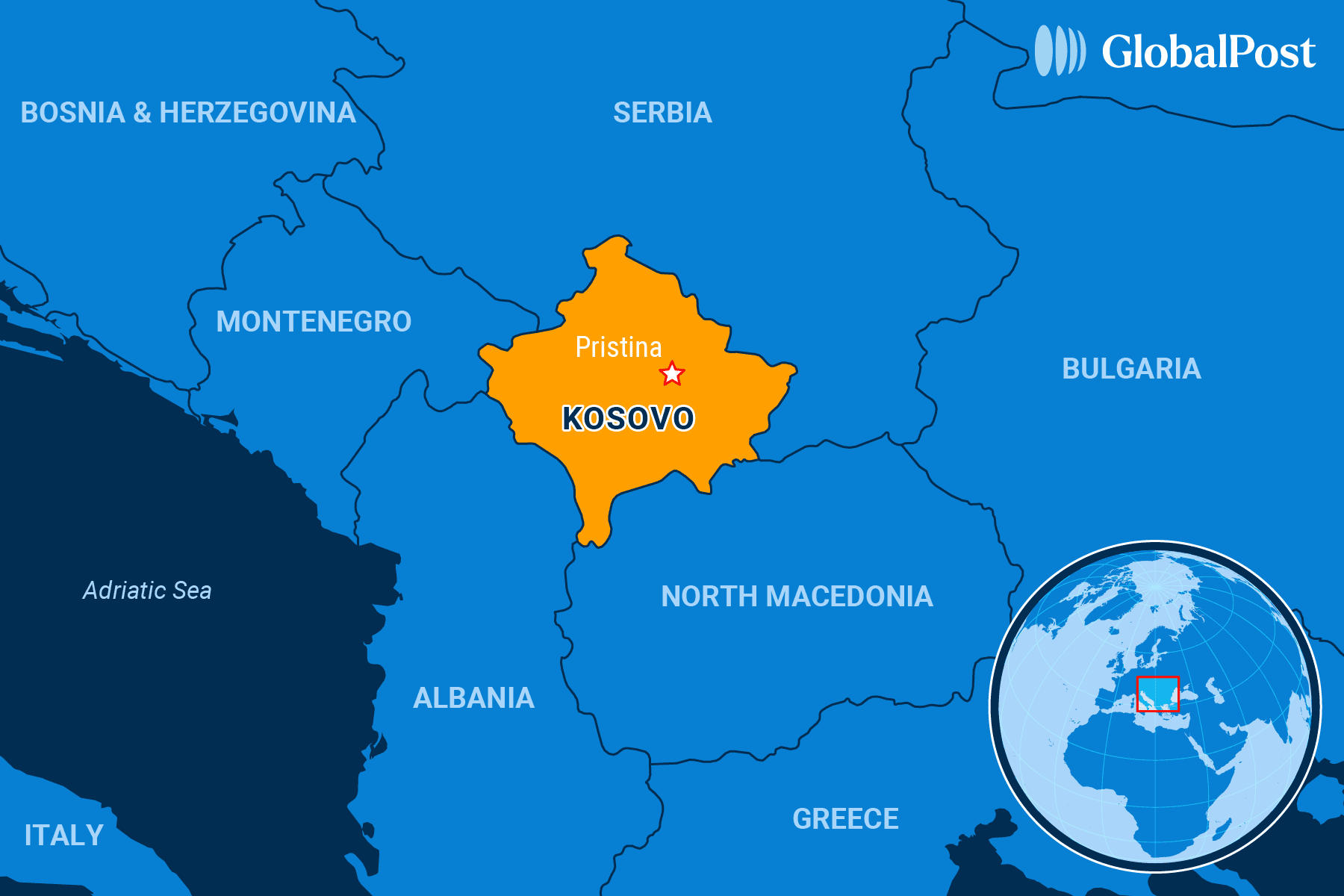

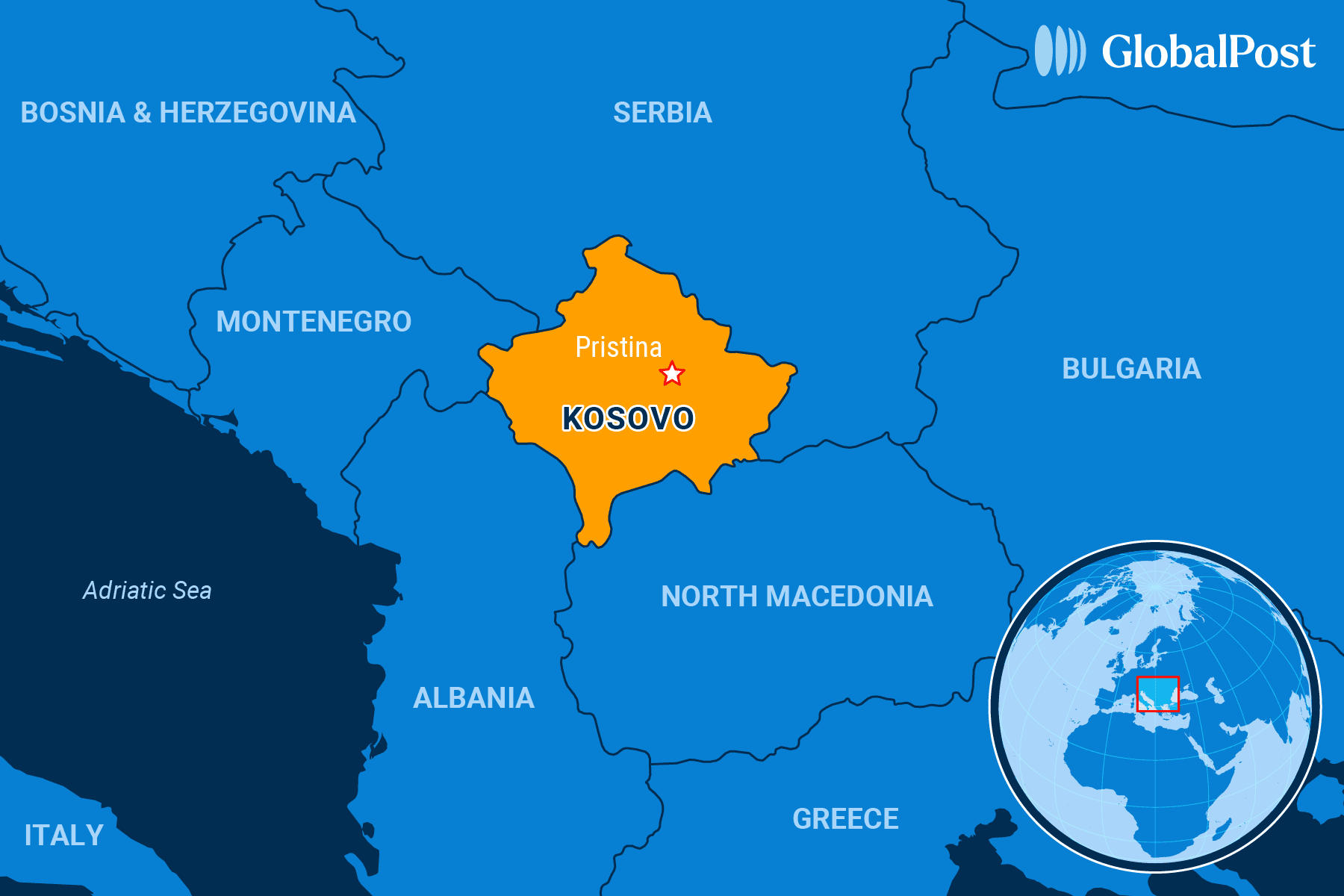

Kosovo, a former Serbian province, became independent in 2008 nine years after a NATO bombing campaign ended a war between Serbian government forces and ethnic Albanian separatists in Kosovo. Serbia does not recognize Kosovo’s independence.

Since then, relations between Kosovo’s Albania majority and its Serbian minority backed by Serbia have been rocky. The spike in tensions came after European Union- and US-backed negotiations between Kosovo and Serbia all but collapsed in 2023.

Meanwhile, over the past few years, Kosovo’s government began dismantling the bureaucracy of separateness of the Serbian community. For example, Serbians in Kosovo aren’t allowed any longer to drive with Serbian license plates or use the Serbian dinar.

That push to end the “parallel institutions” has intensified in the run-up to the elections.

Earlier this month, Kosovo police raided 10 Serbia-linked government offices across the country, including post offices and banks that used the Serbian currency in ethnic Serb areas. Some of these administrative offices didn’t actually provide any services, wrote Agence France-Presse, but served instead as a symbolic presence of Serbia within Kosovo.

Opponents of the move say it was Kurti’s attempt to score points for the election. But the leader never made a secret of his intentions to wind down Serbia’s remaining presence in the country – it was part of his prior election campaign, France 24 said.

Still, in late December, Kosovo’s election authority barred the main ethnic Serb party, Srpska Lista (Serb List) from running candidates in the election because of its Serbian nationalist stance and its close ties to Serbia. Kurti, meanwhile, considers Srpska Lista as the “political branch … of Serb state terrorism,” the Associated Press wrote.

Srpska Lista called the ban “institutional and political violence” against the ethnic minority, done to score “easy political points.”

Regardless, a few days later, Kosovo’s Electoral Panel for Complaints and Appeals voided the ban. Srpska Lista will run 48 candidates for 10 seats reserved for the minority group in the 120-member parliament.

Analysts say that while the elections don’t pit minority groups against each other for specific seats, the tensions play a large role in the race, which is a test for Kurti, whose governing party won in a landslide in 2021, but isn’t expected to perform as well this time around,

Violeta Haxholli of the Pristina-based Kosovo Democratic Institute think tank told the Balkan Insight.

The two main opposition parties, the Democratic Party of Kosovo (PDK) and the Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK), have been criticizing Kurti’s ruling Vetevendosje party and its leader for being overly optimistic about peace with the Serb minority – and with Serbia.

Still, Kurti is expected to win a third term, say analysts at Ifimes think tank.

Whoever does win the race will have to continue negotiations with Serbia. The EU and the US are pressing both sides to implement the 2023 reconciliation agreement between Serbia and Kosovo. US President Donald Trump, with strong ties to Serbia, is a complicating factor for Kosovo, wrote the European Council on Foreign Relations.

If they don’t, the country may descend into a new war, wrote Germany’s Die Welt. The newspaper said that the Serbian president, Aleksandar Vučić, has already been making threats to take Kosovo by force to complete his “Serbian World” project, and would have Russian backing to do so.

It added that Serbia is just waiting for “the right time.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $46 for an annual subscription, or less than $4 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.