Kua takoto te Mānuka

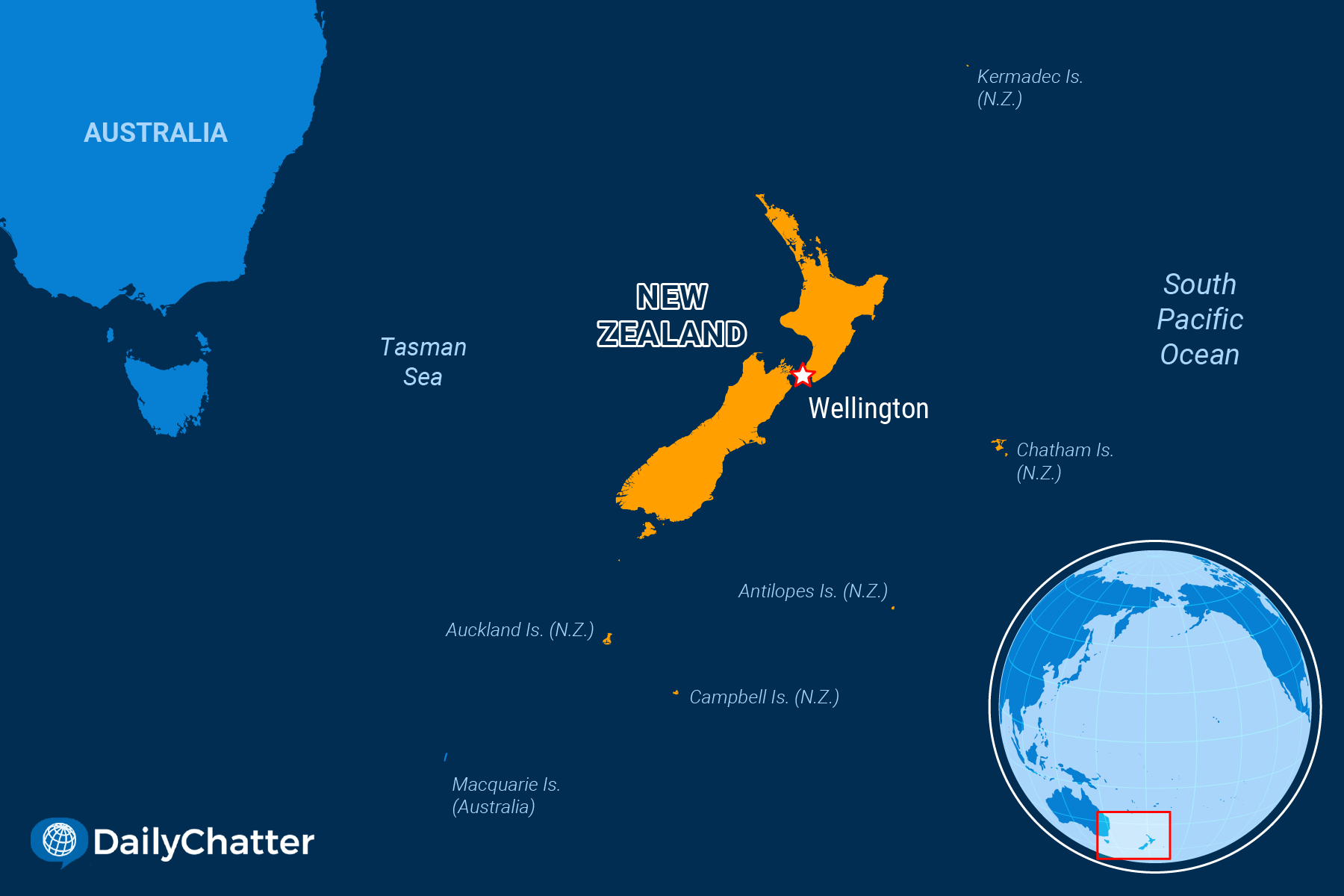

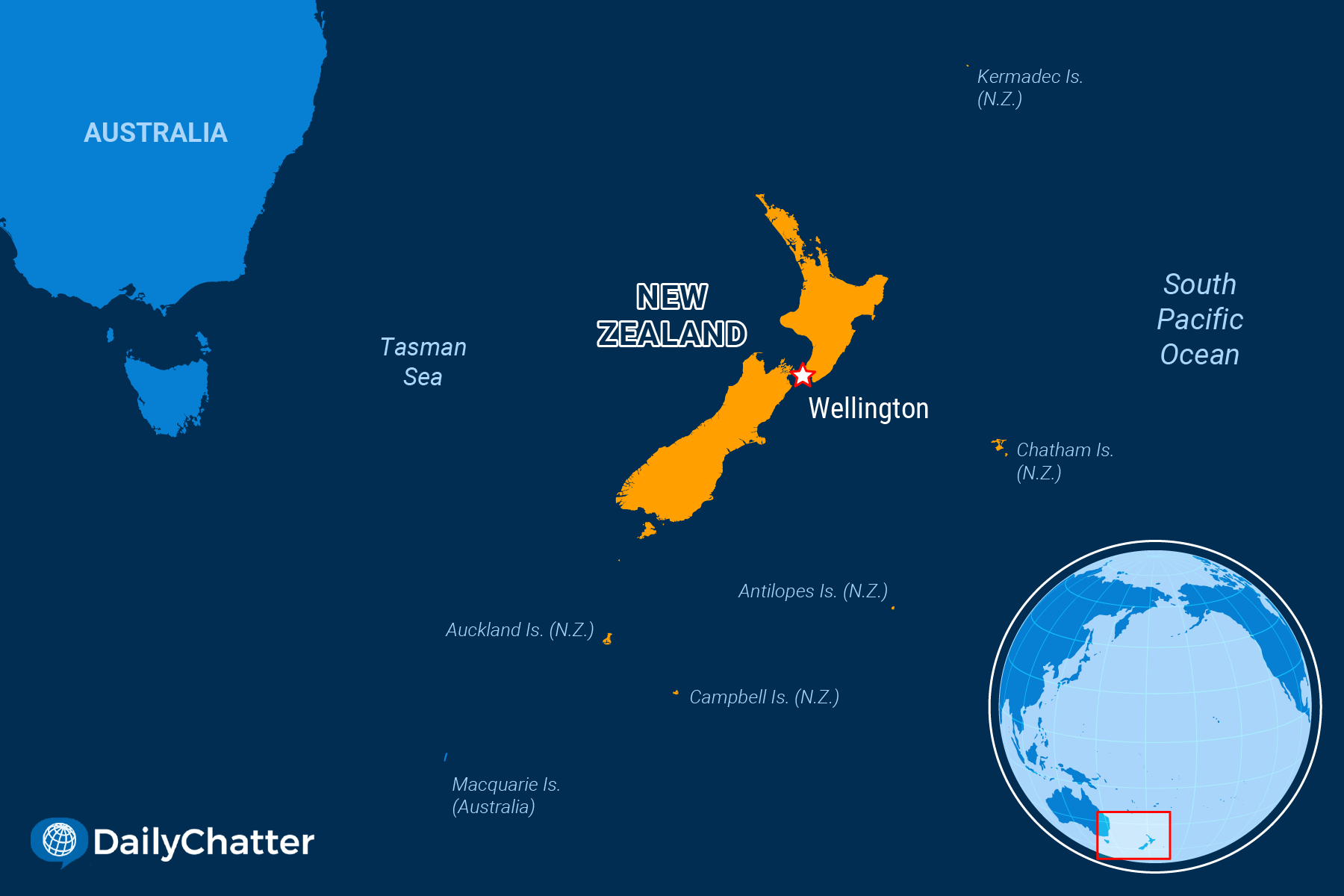

Courses in the Māori language, te reo, are immensely popular in New Zealand, where people of all stripes want to learn how to speak the language of the indigenous people who occupied the islands before they became a British colony in 1840. Waiting lists for the courses are long.

As a result, many Kiwis today are worried that the government’s decision to spend less money on Māori cultural programs could put the courses in jeopardy, wrote Radio New Zealand.

A rightward shift in New Zealand’s politics has dampened officials’ enthusiasm for spending on pro-Māori policies, the New York Times reported. For years, the government invested in cultural programs to boost appreciation of Māori culture, and in social welfare policies to improve Māori citizens’ health, reduce economic disparities, and prevent crime in the Māori community.

Māori males, for example, suffer suicide rates that are nearly twice that of non-Māori males in New Zealand. Women Māoris take their own lives around 1.8 times more than non-Māori women, noted University of Waikato legal scholars in the Conversation.

Māoris have also raised concerns about how New Zealand culture still elides their history. In Invercargill on the country’s south coast, for instance, Māori representatives had to point out that government documents don’t include macrons, the lines above certain letters, as in “Māori.”

In October, however, Kiwis voted in the conservative government of Prime Minister Christopher Luxon, who has pledged to treat all citizens equally, which to him means no longer paying special attention to Māori issues.

Luxon has proposed reversing so-called “co-governance” policies that give Māoris a voice in issues that affect their community, eliminating a new health authority established specifically for Māoris, and canceling programs to clean up waterways in poor Māori areas, noted former Australian diplomat John Menadue in his blog, Pearls and Irritations.

Luxon also repealed a ban on cigarette sales to citizens born after 2008, a policy that aimed to cut high smoking rates in the Māori community, the Independent added.

And ahead of National Day ceremonies on Feb. 6, the anniversary of the founding of New Zealand with the Treaty of Waitangi signed by British colonists and Māori chiefs in 1840 – it establishes and guides the relationship between New Zealand’s government and its Indigenous population – the government was faced with angry Māori leaders because of its announced proposals to review the treaty and implement potential changes to how it affects modern laws.

Meanwhile, multiple protests have broken out since December over the change of direction.

“All the gains we’ve had to beg for are about to be turned back 50 years and we will be forced to try again,” Melody Te Patu Wilkie, a 52-year-old grandmother of six who organized a protest of 400 people in the western town of New Plymouth, told the Guardian. “I’m doing this for my mokopuna (grandchildren) who are too young to have a voice for themselves.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $32.95 for an annual subscription, or less than $3 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.