Meta Action Against Meta: Kenya Hosts Lawsuits Against Big Tech With Global Implications

In April, the European Union fined Meta and Apple almost $800 million collectively for antitrust violations, and added requirements that they change their business practices.

These were only the latest European actions against American “Big Tech” companies for privacy violations, intellectual property infringements, anti-competitive practices, and other actions that the bloc deemed violated its rules over the past decade.

The EU has long been at the forefront of governments and regulators worldwide attempting to change how Meta, Google, Apple, and others do business.

However, it’s three cases in Africa that promise to have even broader consequences for US tech firms, analysts say.

“(These cases) could serve as a model for similar plaintiffs from the global majority to seek some modicum of accountability from one of the most consequential companies of the last two decades,” wrote Compiler, a non-profit that covers digital policy.

One case centers on the death of an Ethiopian chemistry professor, Meareg Amare Abrha, who was the subject of Facebook posts that included his name, photo, and workplace, along with false allegations against him: He was accused of being involved in violence against other ethnic groups as a sectarian civil war raged in Ethiopia in the fall of 2021.

His son, Abrham Meareg, panicked after seeing the posts, worried that the combination of the accusations and the ethnicity of his father, a member of the Tigrayan minority, would cause him to be attacked.

“I knew it was a death sentence for my father the moment I saw it,” Abrham Meareg told NPR.

He repeatedly requested the platform take down the posts. But the company “left these posts up until it was far too late,” he told the BBC. His father was murdered by armed men on motorcycles just weeks later. Some of the posts were removed after his father’s death. Others remained on the site for as long as a year later.

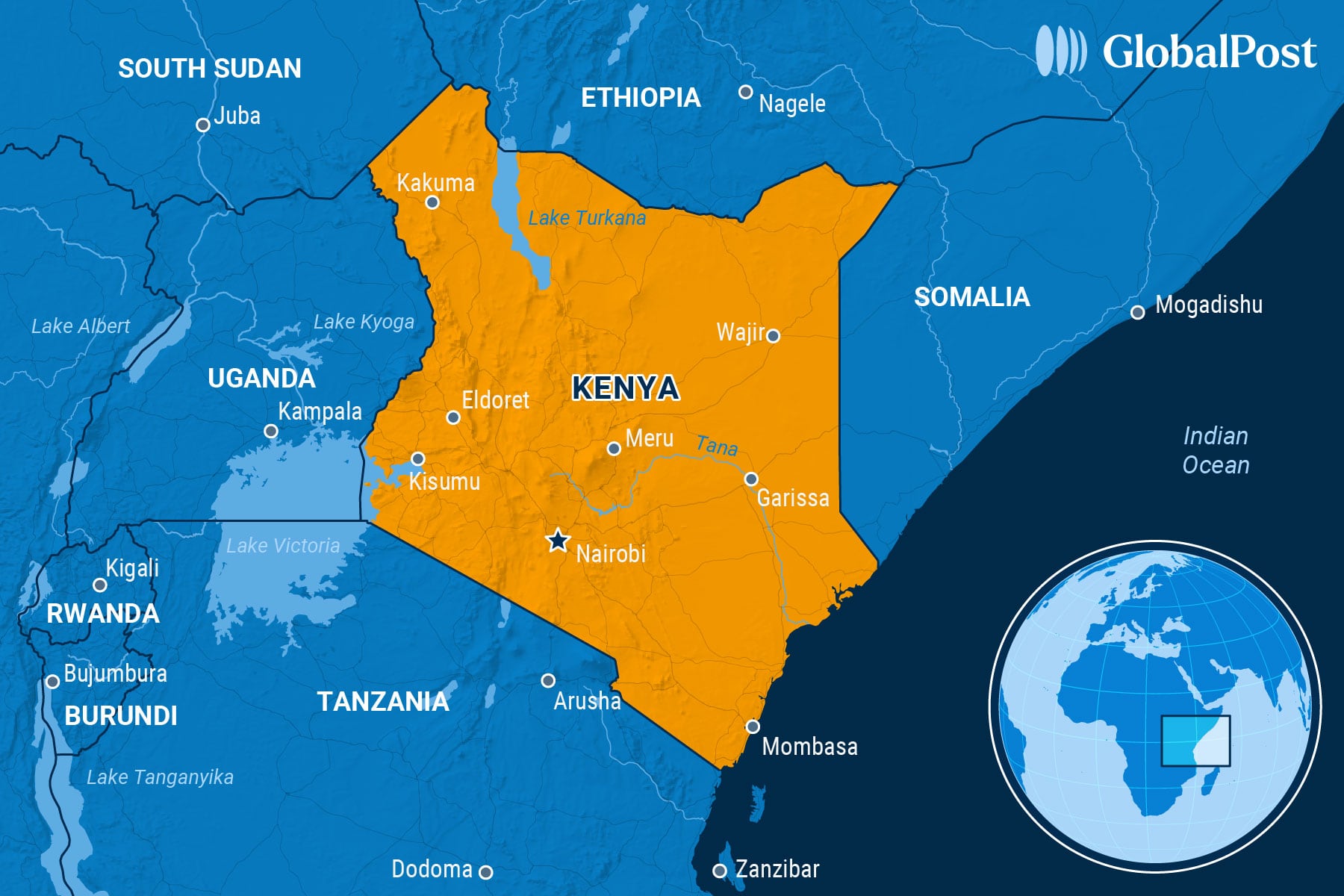

The lawsuit against Meta, filed by Abrham Meareg and two other parties, is asking for $2 billion for a victim’s restitution fund, changes to Facebook’s algorithm, and an apology. The case, filed in Kenya because that’s where the content moderators for Ethiopia were based, alleges that Facebook’s algorithms amplified hate speech that spread hate and violence during the Ethiopian civil war and also led to real-world consequences – such as the murder of Meareg Amare Abrha.

Initially, Meta disputed that it could be held liable in legal action in Kenya since its headquarters are in the United States – an argument it had sometimes used successfully in Europe, until the bloc required the physical presence of American tech companies operating within it.

Meanwhile, liability claims for content posted on tech platforms are rarely successful in the US or anywhere else.

Still, in April, Kenya’s High Court ruled it had jurisdiction to hear the cases.

“(The) ruling is a positive step towards holding big tech companies accountable for contributing to human rights abuses,” said Mandi Mudarikwa, who is in charge of strategic litigation at Amnesty International, which is among the human rights organizations supporting the case. “It paves the way for justice and serves notice to big tech platforms that the era of impunity is over.”

When the case was initially filed, a Meta official told the BBC that hate speech and incitement to violence were against the platform’s rules, saying, “Our safety-and-integrity work in Ethiopia is guided by feedback from local civil society organizations and international institutions.”

Meta says that it will appeal the ruling on jurisdiction in Kenya’s Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, all three Kenya cases center on the tens of thousands of moderators the firm uses overseas to monitor and remove illegal content.

In Kenya, like elsewhere, Meta had hired a third-party contractor, Sama, to perform content moderation in local languages. This is cheaper than incorporating overseas and hiring employees, which subjects the firm to local laws. Firms like Meta had also believed it allowed them to evade liability because it had offloaded the work, analysts said.

In the second of the three cases, a class-action suit, 184 former content moderators say that the contractors hired by Meta, and also Meta itself, were guilty of unlawful termination and forced labor, according to their attorney, Mercy Mutemi, who is also representing plaintiffs in the other cases. In the third, workers accuse Meta and the subcontractors of mental harm, alleging they were forced to watch graphic images without access to mental health professionals and were terminated after they tried to unionize to obtain care.

Meta has said it has no liability because it had no direct relationship with the workers, a claim that a judge in Kenya ruled against, calling Meta the workers’ “employer.”

As the cases continue to be litigated, observers say they are also remarkable because they are the first in Africa or anywhere in the Global South to attempt to hold American big tech firms accountable for their practices.

Moreover, how these cases are decided and what comes after could have global implications for Meta and other multinationals, especially tech companies, analysts say: That they can be held liable for content; that they can be sued anywhere; and that they can be held liable for work performed by subcontractors.

“Kenya has become a key legal battlefield in the campaign to hold Meta accountable,” said Paul Barrett of New York University’s School of Law, writing in Tech Policy Press. “Meta continues to deny legal or moral liability in the innovative Kenyan case. But together with two other lawsuits pending against Meta in Nairobi, the Kenyan litigation provides an unusual opportunity to consider the obligations that powerful technology companies have to the populations that make their mighty profits possible.”

Others point out that beyond the courts, Kenyans and other Africans have additional leverage with multinationals. Africa is the youngest continent demographically – 70 percent of sub-Saharan Africa is under the age of 30 – which makes it an important market for American tech companies in the future, analysts say.

But these cases are advancing even as American tech companies like Meta are moving toward eliminating content moderation completely, reversing a decade-long trend.

Meta, for example, in a January memo said it would eliminate its third-party fact-checking program in the United States this year to “restore free expression,” and instead follow a model used by X, which it called Community Notes.

“Meta’s platforms are built to be places where people can express themselves freely,” wrote its CEO, Mark Zuckerberg. “That can be messy. But that’s free expression.”

“In recent years, we’ve developed increasingly complex systems to manage content across our platforms, partly in response to societal and political pressure to moderate content,” he added. “This approach has gone too far.”

American tech titans have also been lobbying US President Donald Trump to fight governments overseas that are taking action against Big Tech, something he has signaled that he is willing to do.

“We’re going to work with President Trump to push back on governments around the world that are going after American companies and pushing to censor more,” Zuckerberg said.

The lure of jobs and economic growth can sometimes help multinationals avoid such legal cases.

For example, Kenyan President William Ruto is trying to make Kenya into a continental tech hub to promote employment and economic growth. It therefore came as a blow when Meta moved its content-moderation operations from Kenya to Ghana after the lawsuits were filed. (However, Ghana’s content moderators recently filed suit against Meta for mental harm, too).

Now Ruto has backed a new law to make it harder to sue American tech companies because he says the country needs jobs for its young people – currently, about 31 percent of Kenyan youth are unemployed or underemployed, according to the government.

“(This bill would) make us more attractive for investment,” said Aaron Cheruiyot, the Kenyan Senate majority leader, on X. “(Tech is) a growing sector that currently employs thousands with the potential to explode and employ millions. Is it not in the best interest of the ever-growing number of unemployed youth to make do what needs to be done to open up more opportunities for them?”

Essentially, Kenya’s government is facing an impossible choice, Mark Graham of the Oxford Internet Institute told the Economist: “Bad jobs or no jobs.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $46 for an annual subscription, or less than $4 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.