‘The People’s War’

On July 16, two police officers clashing with student protesters at Begum Rokeya University in the northwestern Bangladeshi city of Rangpur allegedly fired 12-gauge shotguns into the chest of 25-year-old student protest organizer Abu Sayed. The birdshot in the shotguns, illegal for suppressing public demonstrations, killed Sayed, wrote Amnesty International.

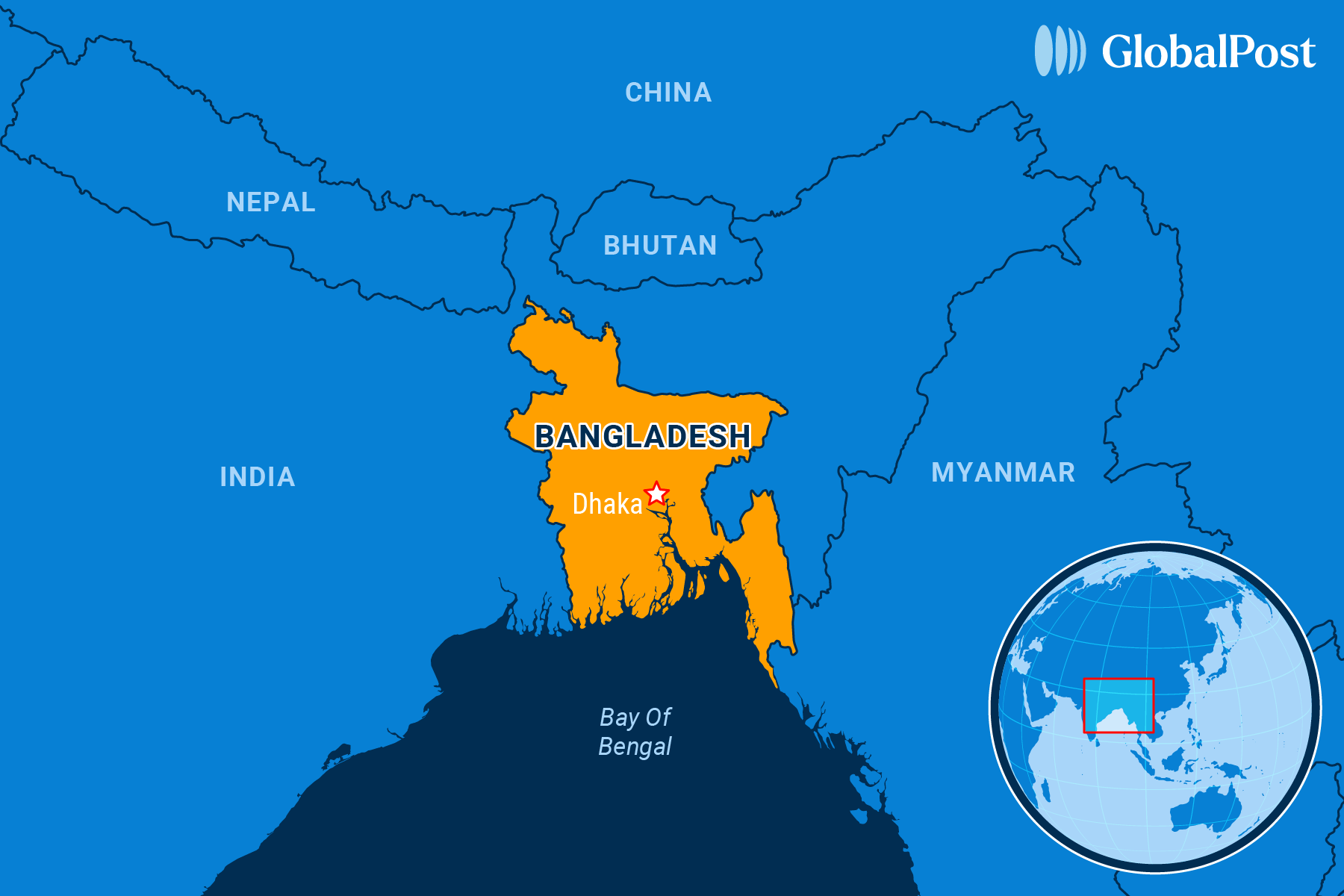

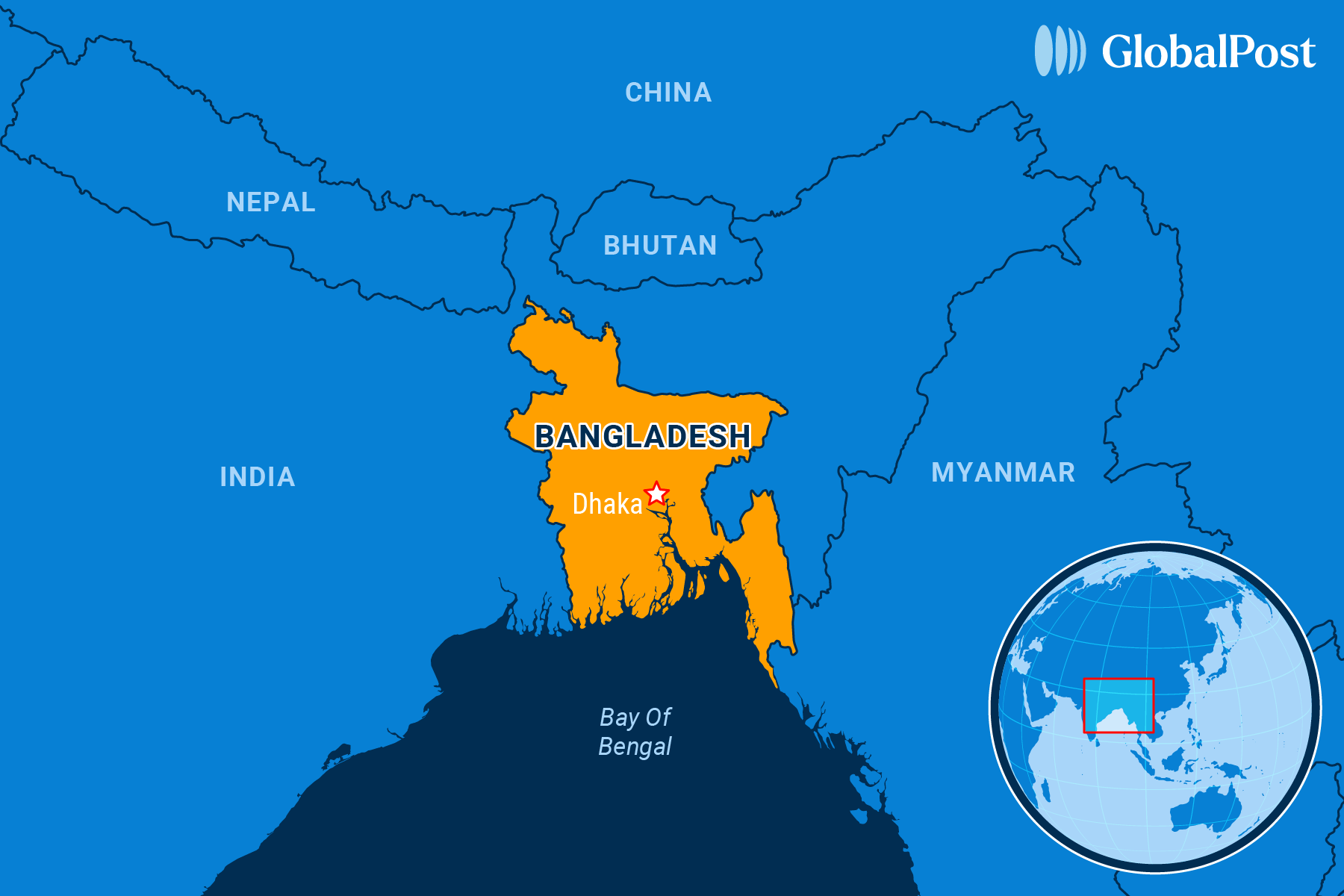

His death was one of hundreds in recent weeks as thousands of protesters have taken to the streets in demonstrations that rocked the South Asian country of 171 million people, and brought life – and business – to a standstill. Police have arrested 11,000 people and targeted more than 200,000 more in 200 cases involving fomenting violence and civil unrest, Bangladeshi newspaper the Daily Star reported.

And on Sunday, when the government instituted a shoot-on-sight curfew, protesters defied it, attacked and burned government buildings and the ruling party’s headquarters, and advanced on the prime minister’s residence. Minutes before they stormed it, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, 76, having been in power this time around for 15 years, fled the country.

The reaction was jubilant.

“It’s a new liberation,” Badiul Alam Majumdar, secretary of the Citizens for Good Governance, told the Washington Post. “Our generation fought for the liberation (from) Pakistan in 1971. This generation fought for another liberation … This was the people’s war, and they have won.”

The startling turn of events that led the daughter of the country’s founding father to resign began weeks ago when protests first broke out over quotas that reserve 30 percent of public sector jobs for people related to the freedom fighters who won Bangladesh’s independence from Pakistan in 1971, the Associated Press explained.

Those quotas, however, too often became a reward for the ruling Awami League and its supporters, critics said, while the young struggled for opportunities, especially as the country has been experiencing an economic downturn marked by high inflation, debt and sky-high youth unemployment.

Soon after the protests broke out, the supreme court ruled to reduce the quota to five percent. But the protests continued, evolving into a broader anti-government movement as ill sentiment across the country against the prime minister and ruling party rose to an all-time high, and began to include people from all walks of life, the Diplomat added. Over the weekend, hundreds of thousands of people took to the country’s streets demanding Hasina’s resignation following cries of excessive force, government mismanagement and endemic corruption, Al Jazeera reported. More than 91 people including 13 police officers were killed. An estimated 32 children died.

Critics say Hasina, known as the “Iron Lady,” who has ruled the country for 20 of the past 30 years, may have started off her career as a pro-democracy icon – she inherited the party from her father who was assassinated in 1975 along with most of her family – but had become autocratic, Reuters reported.

For example, many senior opposition leaders were jailed even prior to the protests while civil rights groups say there have been hundreds of cases of forced disappearances and extra-judicial killings by security forces since 2009.

She also encouraged divisions in the country: She called the protesters “razakars,” (collaborators), a pejorative term for Bangladeshis who helped Pakistanis carry out war crimes during the fight for independence, noted the Times of India. Hasina labeled protesters as criminals engaging in “sabotage” and urged citizens to confront them “with iron hands”. She also blamed the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party for irresponsibly stoking the unrest, and warned that “terrorist” elements were out to destroy the country.

Hasina, who won her fourth consecutive term in January in a controversial election that the opposition boycotted, has often used that refrain when protests have broken out in the past, telling Bangladeshis that she is responsible for the peace, stability and economic progress in the country over in the past 15 years. There is some truth in that, observers say, pointing to how Bangladesh went from being an “economic basket case” a few decades ago to showing economic growth that tops India’s.

“(She) was so disappointed that after all her hard work, for a minority to rise up against her,” said her son, government IT advisor Sajeeb Wazed Joy in an interview with the BBC World Service, adding that she would not attempt to mount a political comeback. “She has turned Bangladesh around – when she took over power, it was considered a failing state, a poor country. And until recently, it was considered one of the rising tigers of Asia.”

Still, her iron fist meant that there was little surprise in the country when over the past few weeks, she turned off Internet services to prevent protesters from organizing, ordered nightly raids on homes in search of student protesters and allowed police to fire live rounds at demonstrators.

But it was too much for many Bangladeshis, and also the respected military, which began to reject her methods of repression on civilians.

Now, new Bangladeshi army chief Gen. Waker-Uz-Zaman says he hopes to get the country quickly back on track. He told the country in a televised address Monday that an interim government would be formed in the coming days and that all deaths over the past weeks would be investigated.

But amid the dancing on in the streets and the red ribbons that have become a symbol of protest, questions about the future linger, especially about a “dangerous vacuum” developing, as the Economist wrote.

The interim government may hope to get things back on track quickly but that is not likely to be easy. Bangladeshi society is deeply polarized and analysts wonder if the chaos and violence will continue or even escalate. At the same time, Al Jazeera noted it would be difficult to rebuild the democratic system quickly after years of the government attempting to eliminate all opposition and fill institutions with their supporters.

Meanwhile, the main opposition party has some of the same issues the ruling party does, including dynastic power politics, cronyism and its own record of oppression when in power, the Economist added. In fact, its leader, jailed former prime minister Khaleda Zia, is the widow of the military officer who took over the country after the coup that killed Hasina’s father, before he too was assassinated in 1981, the BBC noted. Zia, 78 and ailing, was ordered to be freed on Monday.

Regardless, the students said those issues are for another day.

“Now I have seen the victory,” said one protester. “This Bangladesh is now (going to be) made by Gen Z.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $32.95 for an annual subscription, or less than $3 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.