Relief Valve: After Protests, Many Wonder if the Philippine Government Is the Next to Fall

Ahead of mass protests against government corruption late last month, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. told would-be demonstrators that he actually supports them.

“If I weren’t president, I might be out on the streets with them,” he said. “Since this (corruption) has all been exposed… do you blame them for going out on the streets?”

Even so, he implored protesters to keep it peaceful: “Let them know, shout it all out, demonstrate… but just keep it peaceful, because once it’s no longer peaceful, that becomes difficult…”

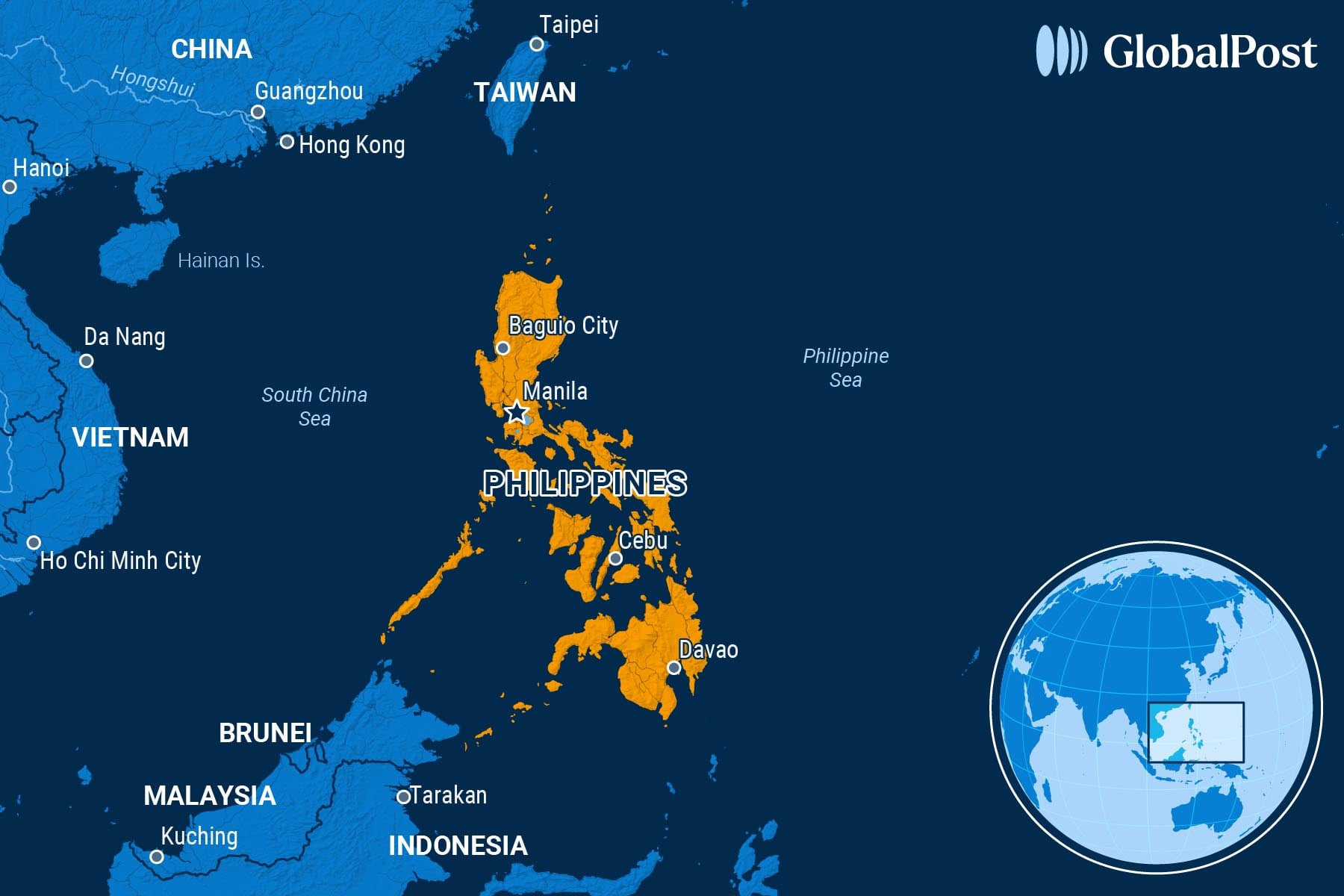

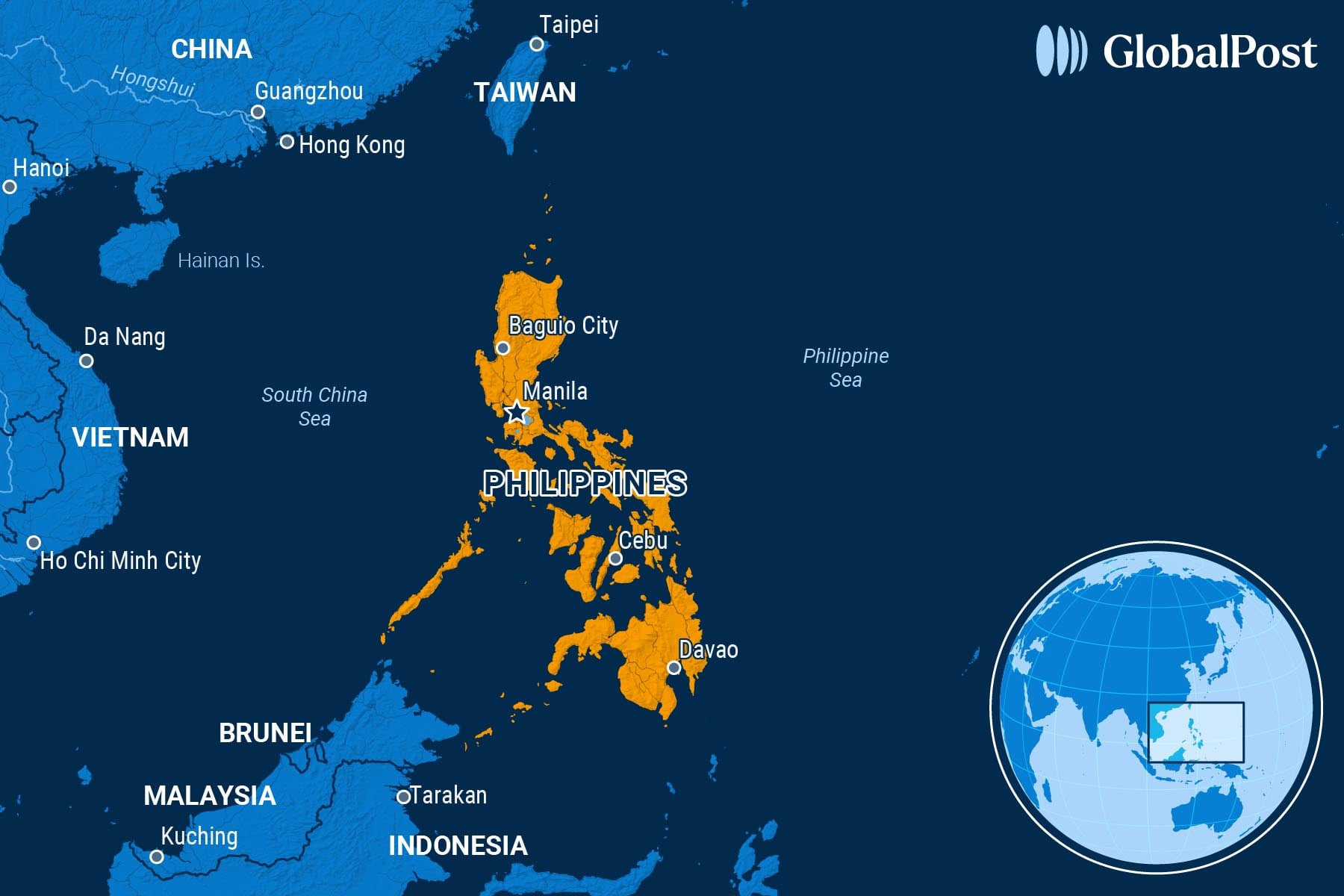

On Sept. 21, tens of thousands of protesters took to the streets across the country in the Trillion Peso March, the first of what organizers say will be multiple demonstrations and strikes. Things didn’t remain calm everywhere, however.

More than 200 people were arrested, including children, following clashes between police and protesters in Manila, leaving one person dead and hundreds wounded. Vehicles, businesses, and other buildings were torched or vandalized. Meanwhile, Amnesty International called for investigations into the use of excessive force by police against peaceful protesters.

The impetus for the protests was allegations that surfaced in the summer by Marcos, himself, centering on a wealthy couple who ran several construction companies that won lucrative flood-control project contracts: They did “substandard” or non-existent work to compensate for significant kickbacks to legislators, construction companies, and public works engineers. Still, in media interviews, the pair showed off dozens of European and American luxury cars, including a British luxury car costing 42 million pesos ($737,000) that they said they bought because it came with a free umbrella.

The president then established an independent commission to investigate what he said were anomalies in many of the 9,855 flood-control projects worth more than $9.5 billion since he took office in mid-2022. He called the scale of corruption “horrible,” filed graft complaints against those involved, and accepted his public works secretary’s resignation. The speaker of the House of Representatives, his cousin, also resigned.

Since then, Filipinos have been glued to their televisions as both houses of Congress conduct probes on air.

The Philippine government estimates the economy has lost up to $2 billion from 2023 to 2025 due to corruption in these projects. Greenpeace, meanwhile, has estimated the cost in that period to top $17 billion.

In the impoverished country regularly ravaged by flooding – this summer, floods and landslides killed more than 30 people and left more than 200,000 people displaced – the contracting scandal ignited fury.

“We wallow in poverty and we lose our homes, our lives and our future while they rake in a big fortune from our taxes that pay for their luxury cars, foreign trips and bigger corporate transactions,” student Althea Trinidad, who participated in the protests in Manila, told the Associated Press.

Now the question many are asking in and outside of the country is whether the Philippines will follow Nepal and Indonesia: Nepal recently ousted its government after mass protests over corruption and inequality, while large Indonesian demonstrations remain ongoing.

“It’s a question that has worried many people in light of what’s turning out to be the Philippines’ biggest corruption scandal in our (recent) history,” wrote Philippine news outlet Rappler. “The precursors for some kind of an uprising are certainly present. But violent riots on the scale of what happened in Indonesia and Nepal have not really happened in the Philippines since February 1986, when angry Filipinos forced the Marcos family to flee Malacañang.”

The newspaper added that because the government was allowing for the protests and strikes, investigating the corruption, and moving to punish the perpetrators, it may avoid what occurred in Nepal and Indonesia.

Others noted that there were few calls for the government to step down in a country that has kicked out its leaders with mass protests twice in the past three decades: Marcos in 1986, and former president Joseph Estrada in 2001 after mass protests following his “farcical” impeachment trial involving corruption.

“This protest is not per se against (President Ferdinand) Marcos Jr. but the culture of corruption,” Georgi Engelbrecht of the International Crisis Group, told Anadolu Agency. “For a long time, Filipinos knew this was an open secret that bureaucrats and local officials take kickbacks for certain projects. What made these protests so relevant is that they happened at a time when the Philippines is being confronted by the climate crisis…”

Even so, the protests occurred on a date that Filipinos mark the anniversary of the takeover by the current president’s father, dictator Ferdinand Marcos, Sr., in 1972, who plundered the country. The Marcos family has not “adequately answered” calls by activist groups to return the stolen wealth, which some estimates put at $30 billion, wrote the Asia Times.

Meanwhile, some protesters are cautious in calling for the resignation of Marcos since this would make Vice President Sara Duterte, currently in the middle of a corruption scandal herself, the country’s new leader. Many also do not want the return of a Duterte administration – her father, Rodrigo Duterte, was Marcos’ predecessor.

Still, public discontent is broader than just the corruption scandal; it is also about crushing poverty, a lack of opportunities for the young, and inadequate infrastructure, analysts said.

“The violence that erupted between young protesters and the police gave face to the deep anger, despair, and desperation among the ranks of the poor (even as) authorities are now depicting the youth protesters as crazed misfits who only meant to sow violence and destruction,” wrote the Diplomat. “What they fail to see is the rising discontent among the youth who feel neglected by a system that favors and protects the rich and powerful.”

“The president thinks he can control the narrative and the direction of the anti-corruption movement,” it added. “The September 21 protest…provided a vivid demonstration of how the seemingly predictable anti-corruption campaign initiated by no less than the president himself could turn into another political force with a potentially disruptive impact on society.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $46 for an annual subscription, or less than $4 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.