A Country, a Business

Starting on March 2, Tajik voters will go to the polls to choose their new lawmakers. And although there are multiple candidates, no one believes the election will change anything in the country that has been ruled by authoritarian leader Emomali Rahmon for more than three decades.

Instead, the buzz these days here is about succession, specifically when the president’s son, Rustam Emomali, will succeed him. Many believe it could be this year.

The rumors of regime change have been flying around for years. But now, observers point to a recent uptick in the harassment of civil society groups and opposition politicians, and a purge of government officials – including members of the leader’s own family – and say that is Rahmon clearing the road for his son.

“The vast extent of the personnel moves has political tea-leaf readers in Dushanbe thinking that Rahmon is clearing the way for his son to assume the leadership of the country, removing potential opponents to the dynastic transition, and installing more pliable figures in their place,” Eurasianet noted.

Since independence in 1991, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Tajikistan has never held a free and fair democratic election. Anyone perceived to be a threat to the leadership, including opposition politicians and journalists, has been sidelined, persecuted or jailed. And since rising to the top job in 1992, Rahmon has expanded his hold on the country, extending his presidential term by amending the constitution: In 2016, the Tajik parliament amended the constitution to formally give Rahmon the title “Leader of the Nation” and the right to run for president as often as he likes. He won his fifth term of seven years in 2020.

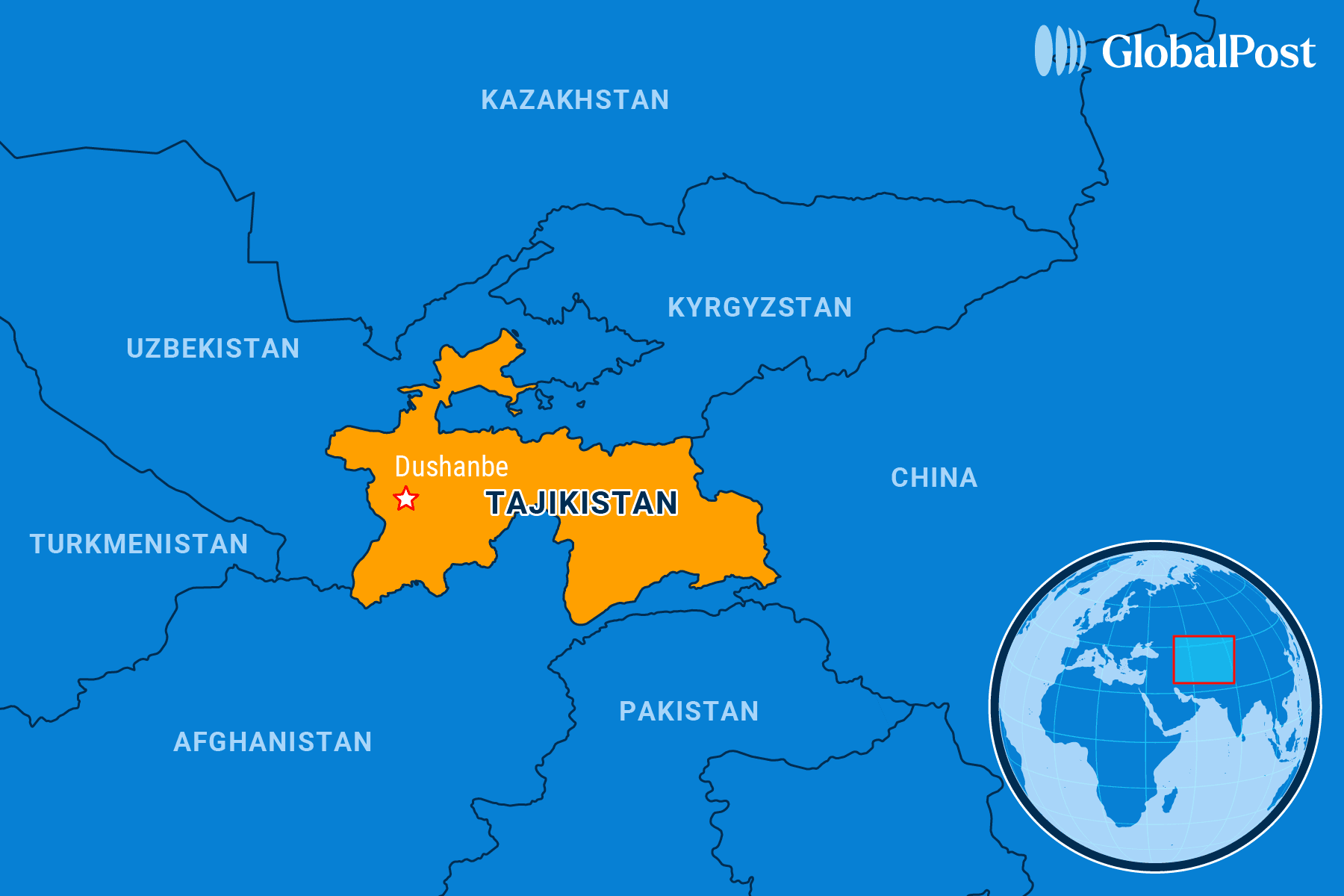

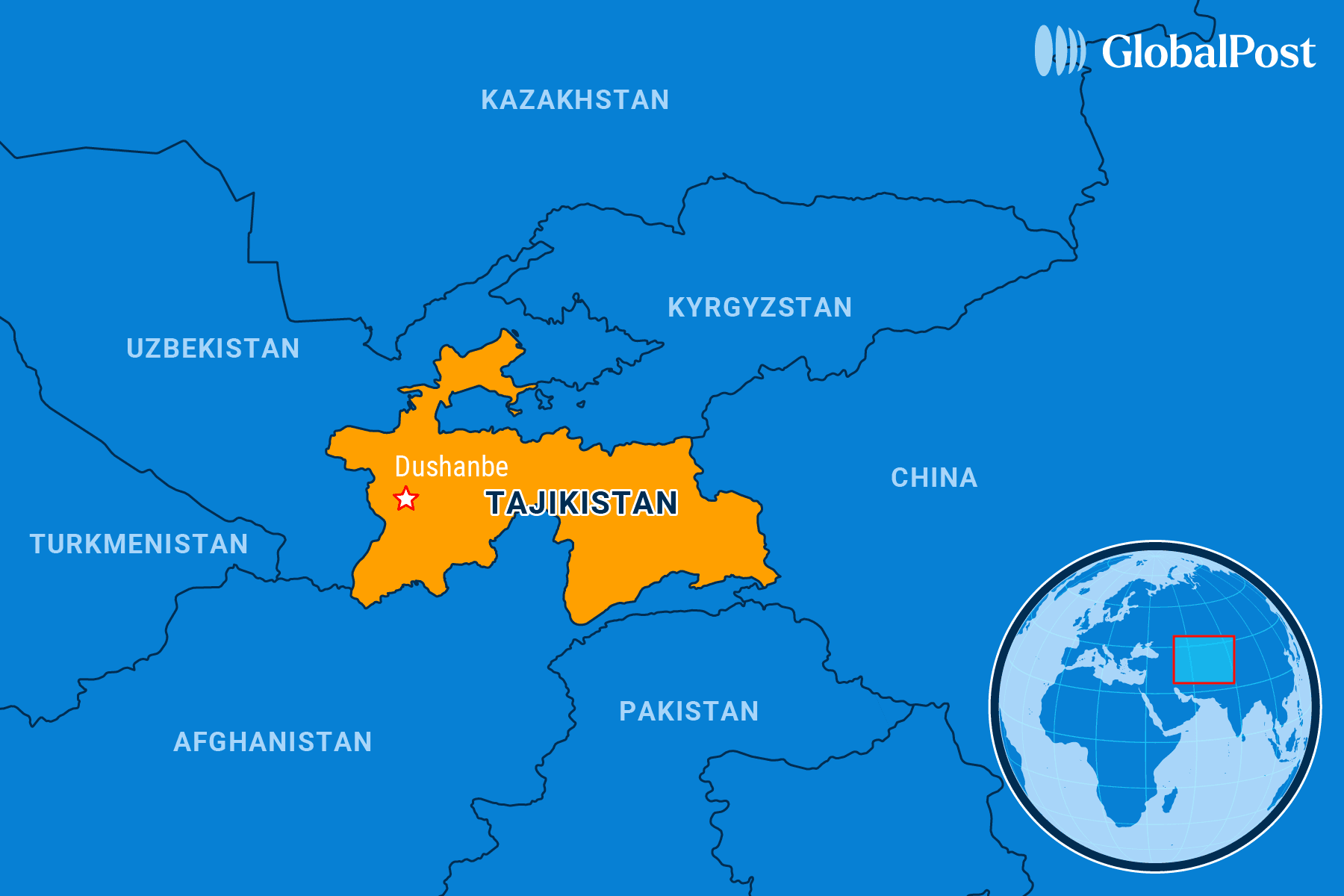

As a result, Rahmon is now Central Asia’s last true Soviet dictator, say observers, outlasting his counterparts in Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan. And now Tajikistan is the last of the so-called “Stans” to undertake a leadership transition.

And to do so, the government has been going after friends and foes alike, say analysts.

For example, on Feb. 5, a court in the capital Dushanbe, in a closed-door trial, sentenced multiple officials for organizing a “coup d’état.” Those accused included the leadership of the opposition Social Democratic Party, as well as former lawmakers and government officials such as an ex-foreign minister and a previous chairman of the Supreme Council (parliament). They were found guilty of crimes against humanity and sentenced to prison terms ranging from 18 to 27 years.

All the defendants denied the charges. They are mostly in their 60s and 70s, and most of them have spent their lives serving the state as loyalists of the regime, noted the Diplomat, adding that “the case seems strange.”

Even odder, said observers, was that the government was targeting politicians who had long supported Rahmon’s government. “Indeed, some of those arrested and detained in 2024 are supporters of the government, and if they were critical, it was very mild,” Hugh Williamson of Human Rights Watch said in an interview with RFE/RL’s Tajik service.

But others say the implications are clear. “It’s hard to imagine … that the ‘coup’ has no connection to the regime’s preparations for the transition of power,” wrote Carnegie Politika.

Still, it has been clear that Rahmon has been positioning his son as the country’s new leader. For example, after he was appointed as mayor of Dushanbe, the Tajik constitution was amended in 2018 to lower the age of eligibility for the presidency to 30 to accommodate Rahmon’s son’s age, who was then just 31.

Then, in 2020, he was elected to chair the upper house of the legislature. If Rahmon died tomorrow, under the constitution, Rustam would become president.

Now, Rustam is building his own team for this transition, say observers.

To date, there aren’t many other clear successors. That’s partly because the president’s family, which includes seven daughters and two sons, has the country locked up. His eldest daughter, Ozoda, is chief of staff, and her husband is number two in the central bank, while his other daughters and their spouses hold key positions in the government or in various sectors of the economy, such as transportation, media, banking, pharmaceuticals, and mining.

“Many countries are led by an authoritarian elite … But few are as dominated by a single ruling family as Tajikistan,” wrote the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP). “Anything of value in the country – from mining licenses to driving schools and even to medicinal plants – is quickly snapped up by President Emomali Rahmon and his relatives.”

Still, observers say the president has been reshuffling government agencies while also firing or reassigning family members, suggesting that not all are on board with his choice of successor.

That’s because a new president could lessen the influence and the funds the current family members – and regional elites – have access to.

Regional analyst Galiya Ibragimova says it’s the president’s own legacy of authoritarianism, nepotism, and greed that is threatening his succession.

“By directing all the streams of income and control of the country to his own relatives, Rahmon has painted himself into a corner,” she wrote. “Infighting over the succession and growing frustration in the regions could shatter the stability that the president has been building for so many years. Power transitions rarely go to plan in Central Asia, and Tajikistan may be no exception.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $46 for an annual subscription, or less than $4 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.