The Pressure Cooker

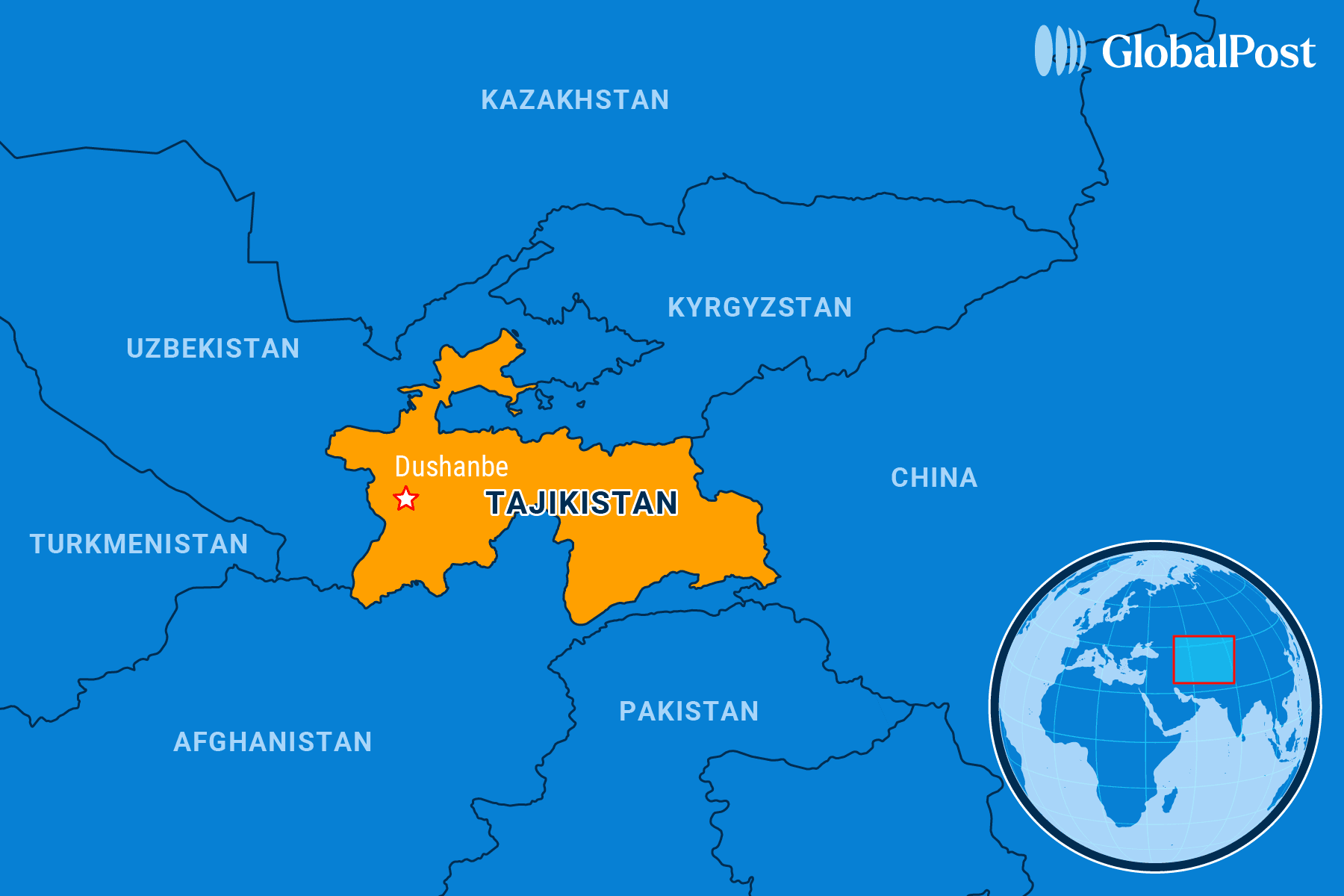

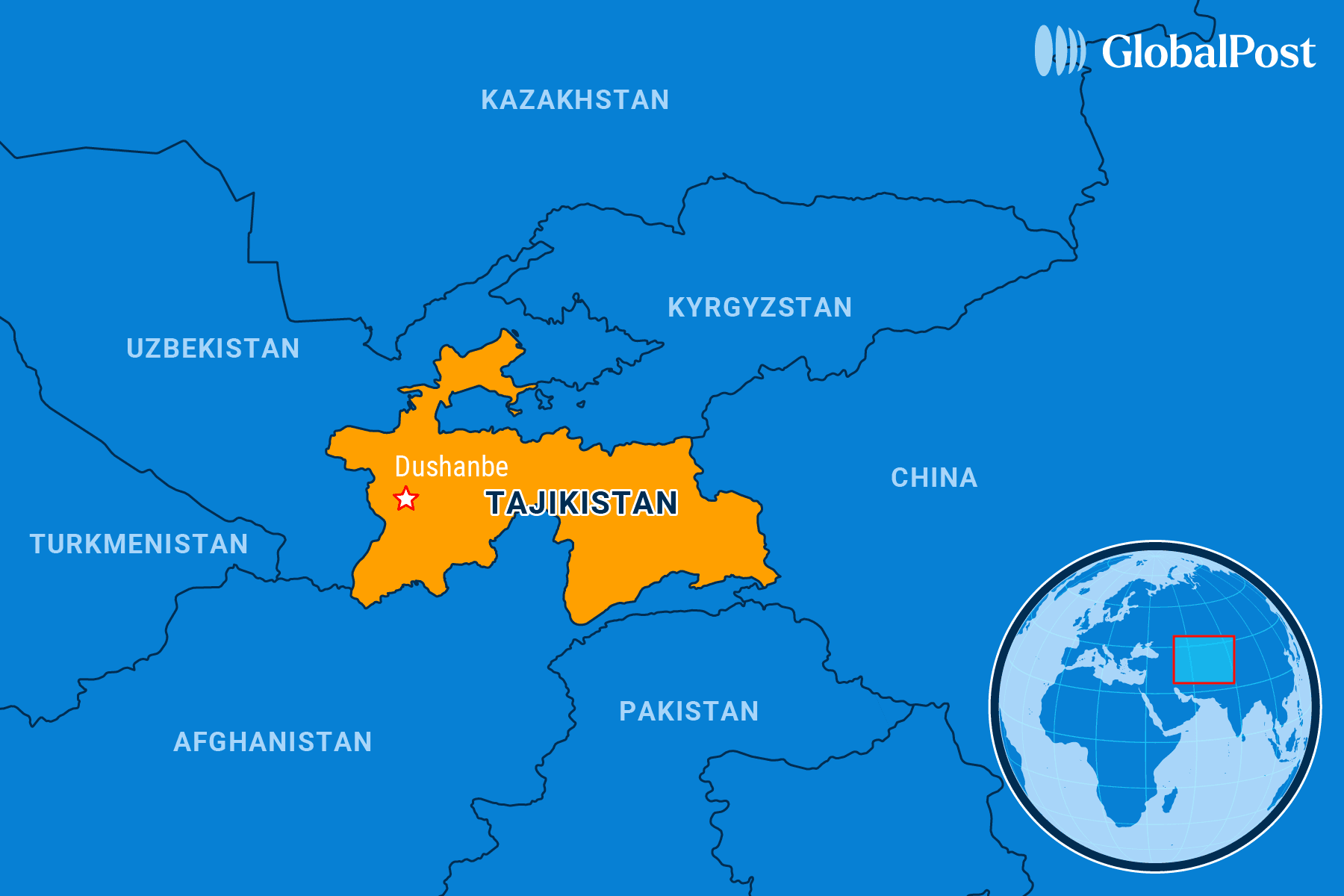

A statue of Ismoil Somoni is a big attraction in Dushanbe, the capital of the former Soviet republic of Tajikistan. In the 10th century, he ruled over an empire that included parts of what are now Afghanistan, Iran, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. “Somonis” is the name for Tajikistan’s currency.

Tajik President Emomali Rahmon – who has been in office since 1992 when he and his fellow former Soviet elites fought a four-year civil war against liberal democrats, nationalists and Islamists that resulted in as many as 150,000 deaths – has promoted Somoni as well as other Persian figures in recent years.

As Le Monde diplomatique reported, this mythologizing of Tajikistan’s Aryan past has been Rahmon’s way of building a sense of Tajik national identity.

It’s also likely one reason why Rahmon recently decided to ban women from donning attire including the hijab, the black veil that many Muslim women wear, even though 97 percent of Tajiks are Muslim, wrote Euronews. Instead, the government is encouraging women to wear traditional Tajik clothing, or Western garb.

The idea is to suppress religious extremism, say Rahmon’s allies, according to Radio Free Europe, even as some would argue that Islam doesn’t necessarily compel women to wear hijabs. Men with long beards – a common custom in Muslim countries – have also received frowns from officials. Police trimmed the beards of 13,000 men in Khatlon Province in 2015, for example.

Human rights activists say the policy violates civil liberties and freedom of expression, wrote the EU Reporter.

Rahmon has been pursuing these kinds of measures for years. In 2011, lawmakers passed a law banning minors from entering places of worship without permission and punishing parents who send their kids to foreign religious schools. In 2017, the government shut down almost 2,000 mosques, converting many into tea shops and health clinics.

Critics don’t believe the hijab ban will work. Tajikistan is one of the poorest countries in Central Asia, and Tajiks have few economic opportunities at home. Instead, many leave for menial jobs in Russia. Others opt for Islamic militant groups because they believe radicalism provides them with more dignity and options for the future, argued Emerging Europe. Rules about clothing won’t change those conditions, it added.

Tajikistan certainly has a problem with terrorists. Russian authorities say the terrorists who attacked Moscow’s Crocus City Hall in March, killing 140 people and injuring 360, carried Tajik passports, for example, reported TRT World.

Nazila Ghanea, the United Nations human rights agency’s special rapporteur, believes the restrictions are counterproductive, the news organization added, stressing that it plays a strong role in promoting radicalism within society.

That’s exacerbated by “Tajikistan’s geographic isolation, weak economy and repressive government, (which) will leave it particularly vulnerable to destabilization and becoming a hotbed for radicalization for the foreseeable future,” wrote analytical group Stratfor, adding that a looming succession crisis due to the ailing and aging leader (who’s 71 years old) could inspire even more radicalization among the population.

Meanwhile, there’s another crackdown on belief in the country – the government announced in late August it would suppress witches, warlocks and their clients, wrote the Times of Central Asia. It appears the government has concerns that “deeply rooted beliefs revolving around the supernatural are a threat to stability.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $32.95 for an annual subscription, or less than $3 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.