The Coming Storm

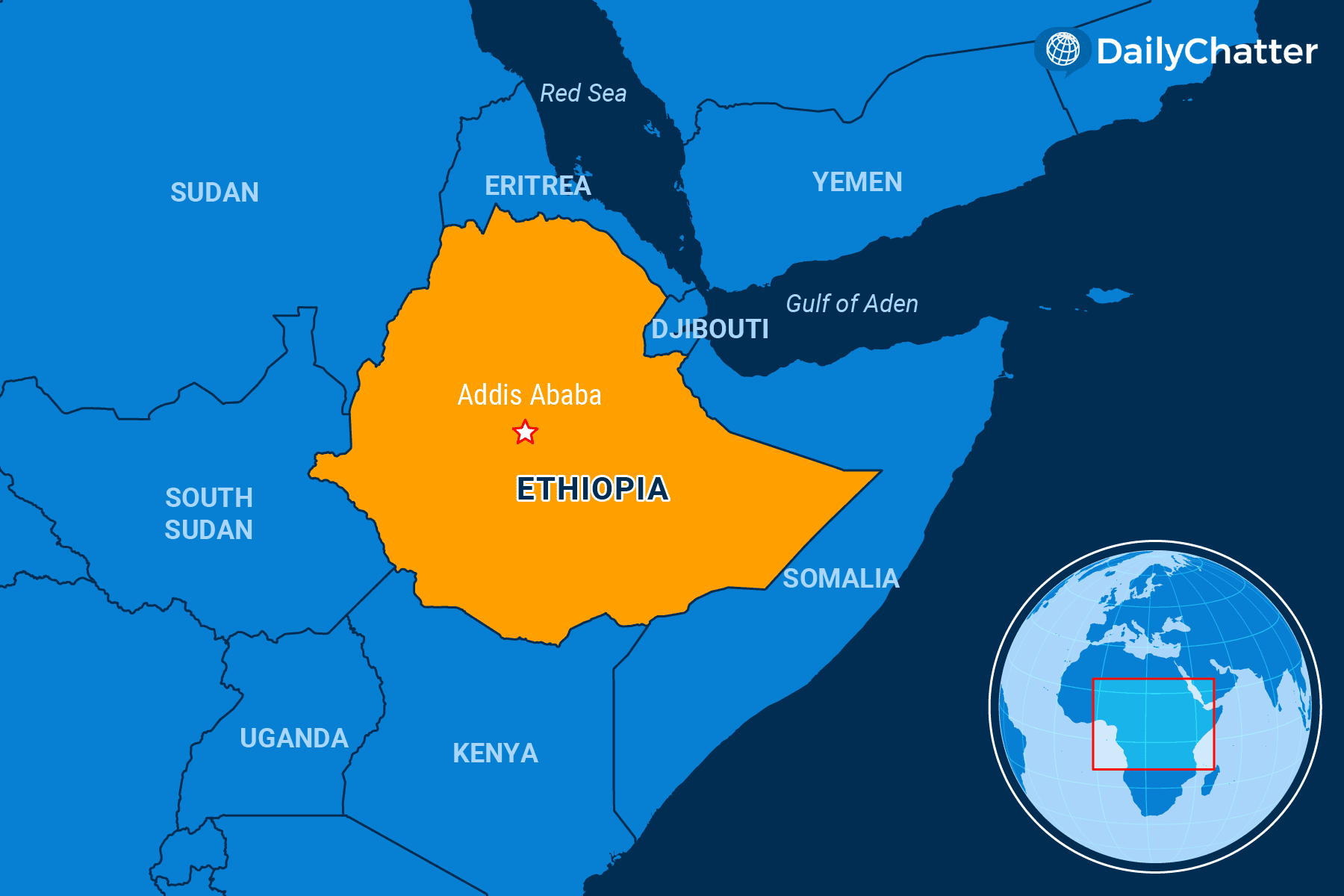

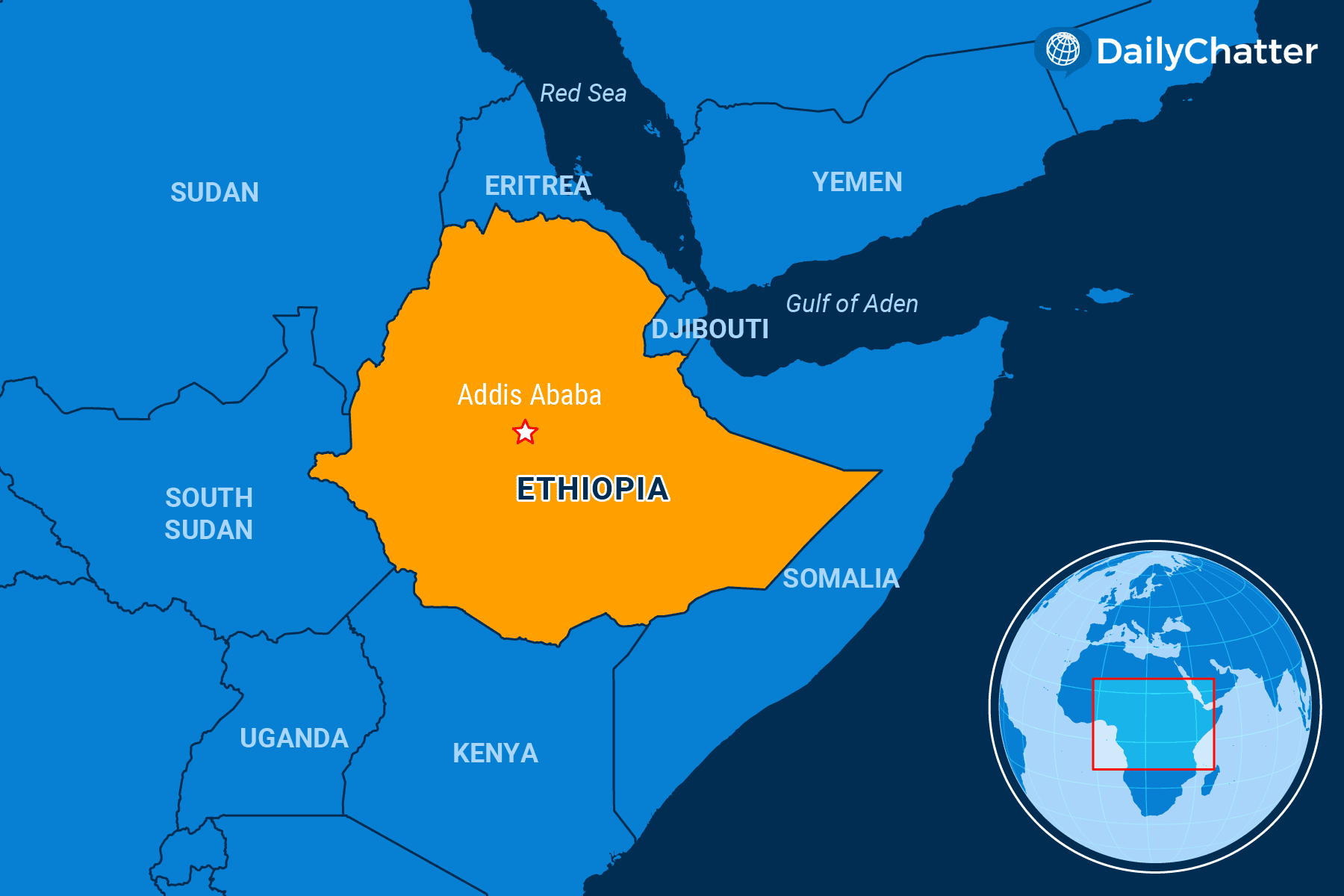

When Eritrea won independence from Ethiopia in 1993, the latter retained access to a port on the former’s Red Sea coast. But five years later, Ethiopia lost access to this port during a war between the two countries that lasted until 2000. Today, Ethiopian trade flows through Djibouti.

Wanting to change this situation, Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed hoped to reach a deal with Somaliland, an independent but unrecognized republic within Somalia, to allow more Ethiopian trade to travel through the port of Berbera, reported Agence France-Presse. Berbera would also allow Ethiopia to trade with the Middle East and Europe to the north via the Suez Canal, and east past the Horn of Africa to India and China.

Many Ethiopians feel this arrangement makes perfect sense, the Washington Post noted. Their country, a growing regional power, was never previously landlocked and should not be so today, they reason. In ancient times, for example, Ethiopia was a stop on sea routes that stretched from Rome to India.

In return for its port access, Ethiopia promised to conduct an “in-depth assessment” of Somaliland’s bid for sovereignty, a milestone for Somaliland, explained Al Jazeera. No country recognizes the self-declared breakaway state. Additionally, Somaliland would receive a stake in Ethiopian Airlines, a state-owned company that could help Somaliland make connections worldwide.

Importantly, as part of the agreement, Ethiopia will also occupy a naval base in Somaliland. Forces deployed to that base presumably could come to Somaliland’s aid in the event of a conflict with officials in Mogadishu.

Somaliland was a British colony until 1960. The territory enjoyed five days of independence before voluntarily uniting with Somalia, a former Italian colony. It was a bumpy union that ended with Somaliland breaking away in 1991, after a decade-long liberation struggle against a Soviet-backed military regime. Today, Somaliland is a de facto independent state, with its own currency, a parliament and overseas diplomatic missions.

Reflecting the import of this diplomatic turn – a foreign power brokering a deal with rebels to use a military post on land they control but which others claim – Somalian President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud condemned the agreement, signing a new Somalian law to nullify it, added Reuters. It’s not clear if this nullification will do anything, however.

“Somalia belongs to Somalis,” Mohamud told lawmakers recently, according to the New York Times. “We will protect every inch of our sacred land and not tolerate attempts to relinquish any part of it.”

Now, Somalia says it is prepared to go to war to stop Ethiopia from recognizing Somaliland and building a port there, a senior adviser to Somalia’s president said, according to the Guardian.

Declaring the deal void, Mohamud has called on Somalians to “prepare for the defense of our homeland,” while protests have broken out in Mogadishu, Somalia’s capital, against the agreement.

At the New Arab, Abdolgader Mohamed Ali, an Eritrean journalist, wondered whether the deal would set in motion events that might ultimately lead to conflict in one of the world’s most volatile regions.

Abiy has hinted at resorting to violence to regain Ethiopia’s historical access to the Red Sea. Eritrean officials, who have been Abiy’s allies – he won a Nobel Peace Prize in 2019 for finalizing a peace deal with Eritrea – are preparing for a potential outbreak of war over the issue.

Djibouti faces economic repercussions from the deal, too, Bloomberg noted.

Ethiopians want access to the sea. The question now is, how far are they willing to go to get it?

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $32.95 for an annual subscription, or less than $3 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.