The Long Arm of the Law: In the Philippines, the Rules Remain an Afterthought

When former Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte was arrested on March 11 on a warrant from the International Criminal Court (ICC) for crimes against humanity, the Philippine public was shocked.

Some protested his arrest, saying the former president is loved for what he did to bring law and order to the streets of the Philippines. Others celebrated, calling the arrest retributive justice for a man who unleashed murderous thugs on the population, killing thousands of people.

“Domestic reaction in the Philippines is deeply divided,” wrote the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, noting that the former president left office with an approval rating of 80 percent.

“(Still), there is no doubt that Duterte’s arrest has brought a sense of optimism for victims of his extrajudicial killings that they will finally get justice,” it added. “Within the Philippines, justice for past atrocities remains elusive, especially when the accused hold powerful positions.”

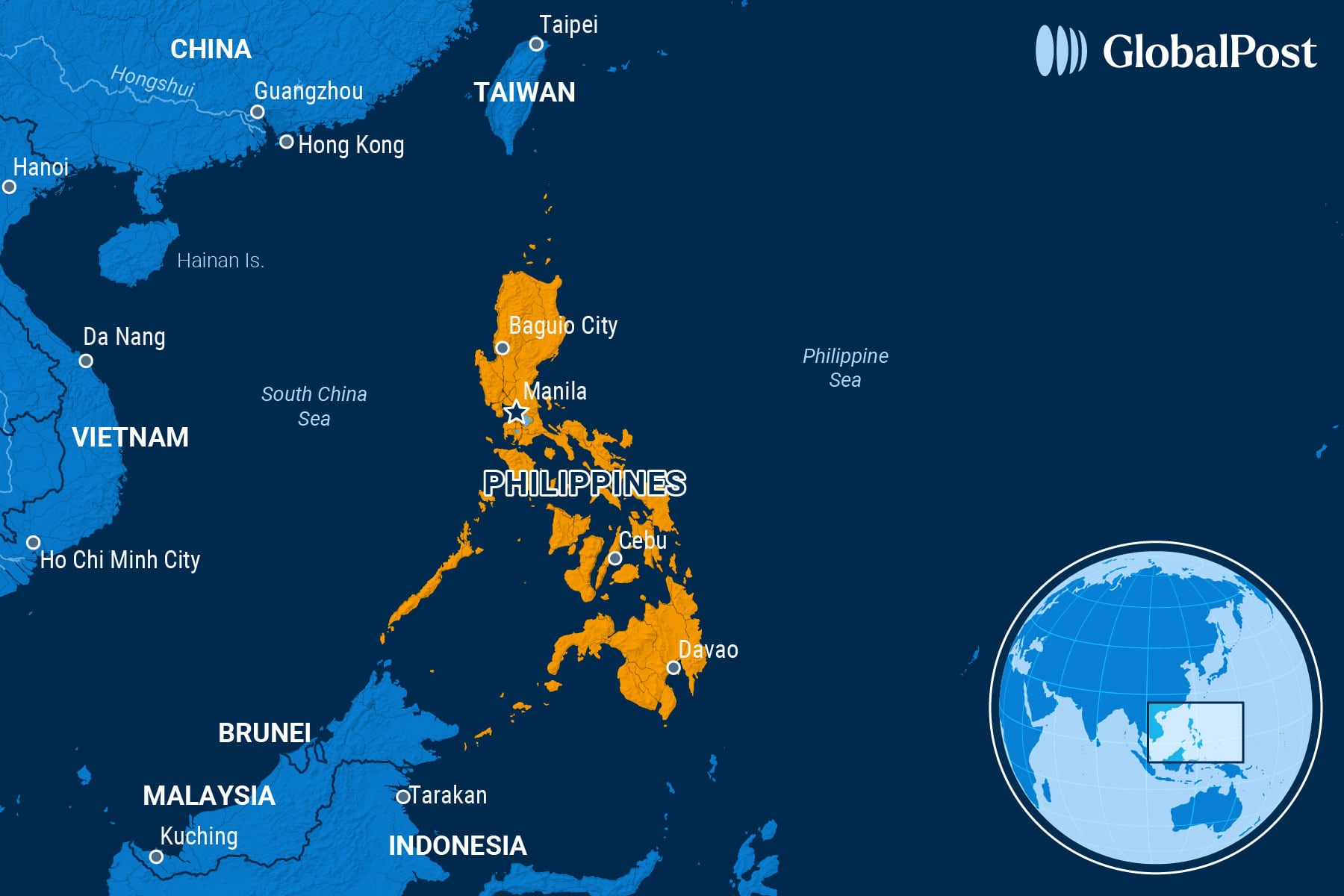

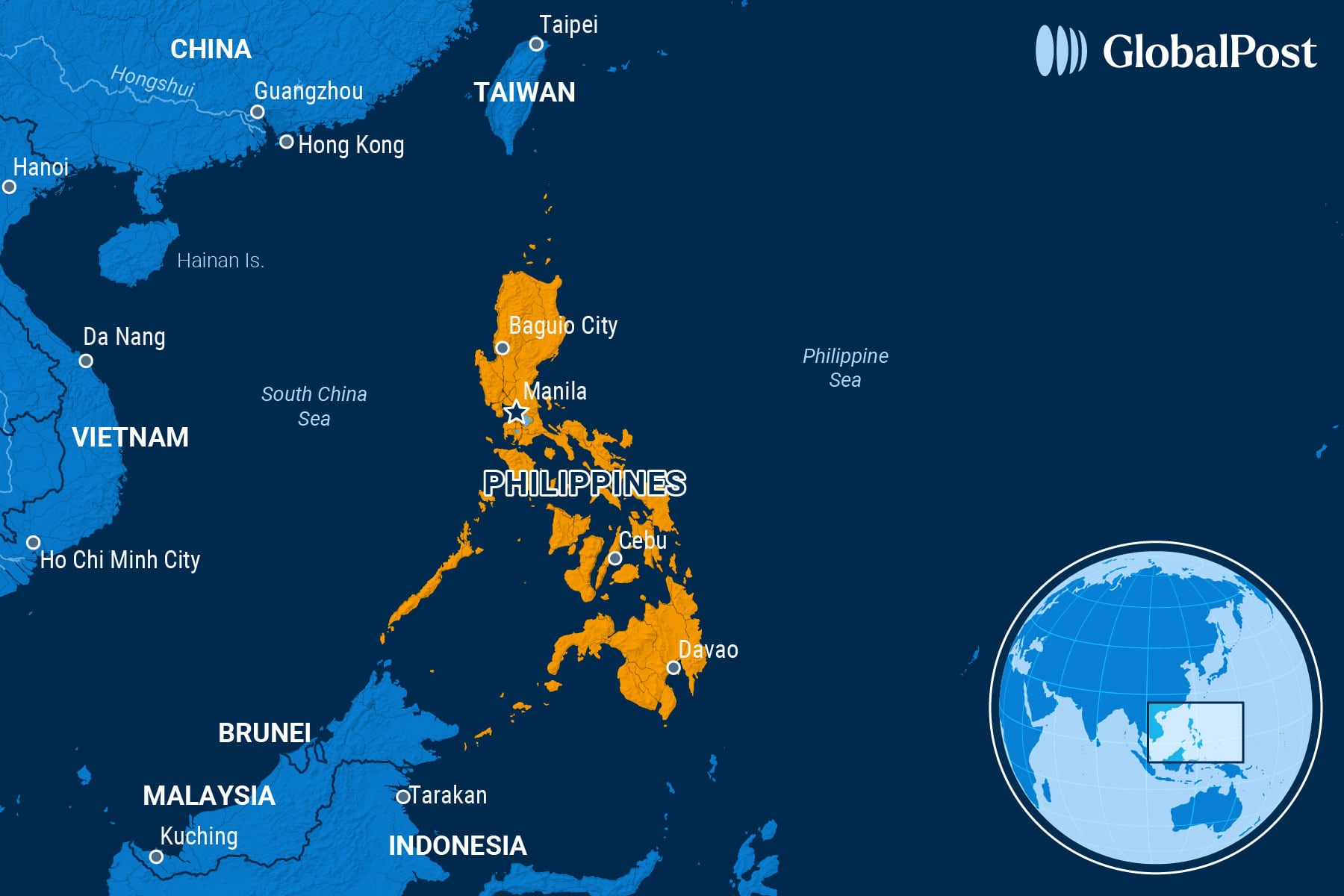

Even before he became president in 2016, Duterte, as mayor of his hometown of Davao, earned the moniker “the Punisher” for his violent war on drugs, which he escalated after assuming the presidential office. He is accused of ordering police and vigilantes to kill thousands of people on suspicion of involvement with drug trafficking, often without proof. In reality, human rights officials say that meant that anyone who could even be tangentially linked to using or selling drugs – even based on a rumor – could be targeted.

As a result, the nationwide drug war killed at least 6,280 accused drug dealers and users, according to the government. The ICC estimates that number to range between 12,000 and 30,000 people from July 2016 to March 2019.

Duterte has long said he was doing what he promised voters. In 2016, during his presidential campaign, Duterte vowed that 100,000 people would die in his crackdown, with so many dead bodies dumped in Manila Bay that it would “fatten all the fish there.”

“These sons of whores are destroying our children. I warn you, don’t go into that, even if you’re a policeman, because I will really kill you,” he said soon after he became president. “If you know of any addicts, go ahead and kill them yourself, as getting their parents to do it would be too painful.”

Testifying before a Senate hearing into the killings in November, Duterte was defiant, saying that he had kept a “death squad” of convicts instructed to kill other “criminals.” “Do not question my policies because I offer no apologies, no excuses. I did what I had to do, and whether or not you believe it … I did it for my country.”

People like Joel Valles, owner of Sana’s Carinderia, a barbecue restaurant in Davao, are grateful to Duterte. Davao used to be a dangerous place, says Valles, with carjackings and muggings a normal occurrence. But that changed when Duterte took office.

“You have to make (the criminals) fear,” he told New Lines magazine. “A lot of hard-headed people, especially drug pushers and rapists were put … six feet under.”

After Duterte stepped down in 2022 due to term limits, his successor, President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr., son of the deposed former president, Ferdinand Marcos, promised to stop the killings and hold those responsible accountable, creating a task force and launching investigations. He said he would focus on community-based treatment and rehabilitation.

But things haven’t changed under Marcos or his vice president, Sara Duterte, the daughter of former president Duterte, analysts say. There is still little to no due process. Meanwhile, there is at least one extrajudicial killing a day. That’s why the ICC, despite requests by the Philippine government over the past few years to do their own internal investigations, said in 2023 that it was “not satisfied” and pressed on.

In fact, in 2023, there were more drug-related killings than the year before, when Duterte left office, noted World Politics Review. These continued in 2024.

“Marcos’ wider promises on the drug war … have proven completely hollow,” it wrote. “In fact, he has shown no inclination to end the extrajudicial killings of drug users that have left Filipinos living in fear.”

As a result, residents of many communities are still afraid, they say.

“Duterte’s gone, but his influence is still going,” one resident of Navotas, a poor city north of Manila with one of the highest concentrations of killings under Duterte, told NPR. “Because of the vigilantes, if you look like you’re using drugs, even if you’re not using drugs, you (are) still killed. There’s no justice.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $46 for an annual subscription, or less than $4 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.