The Power of Vagueness

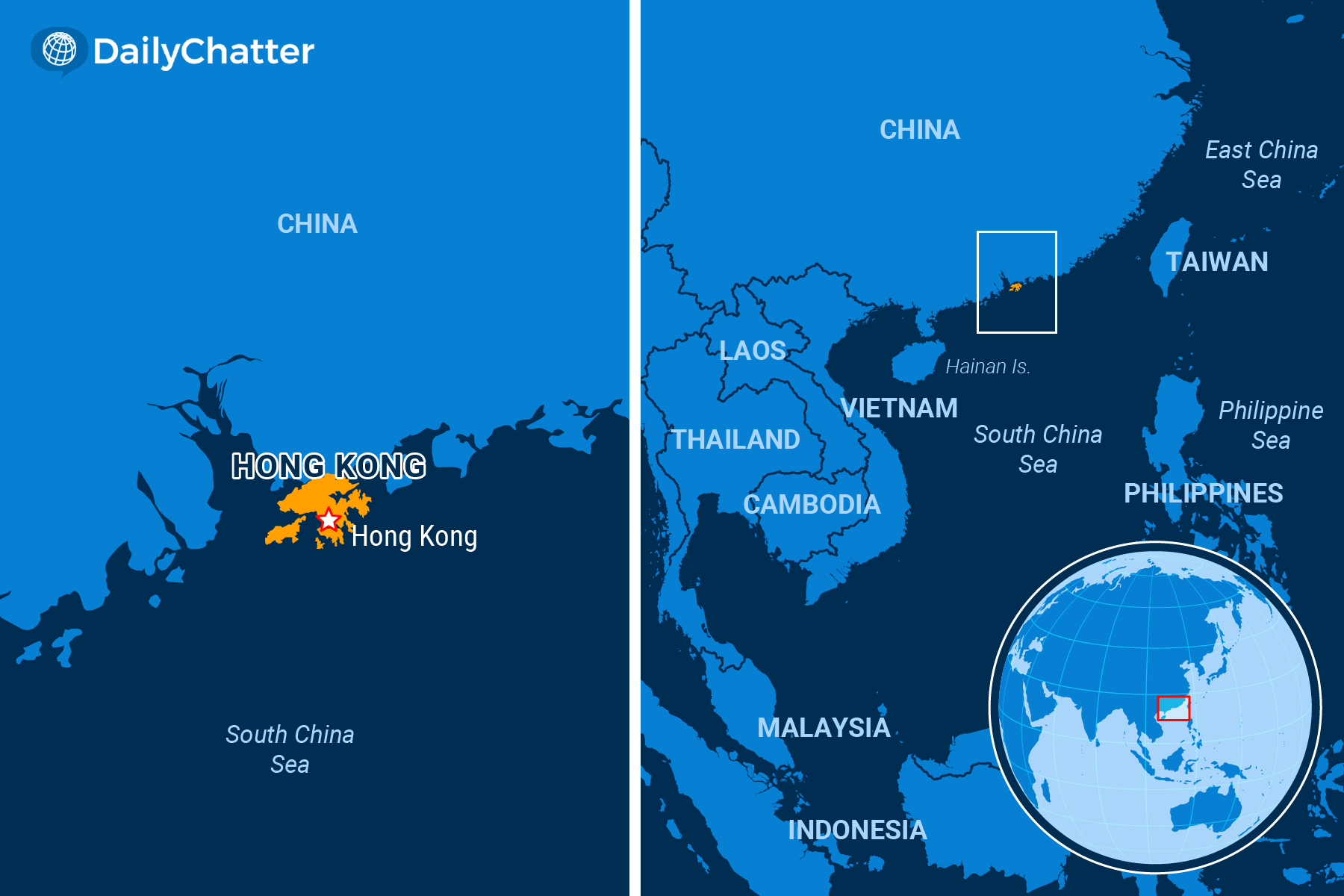

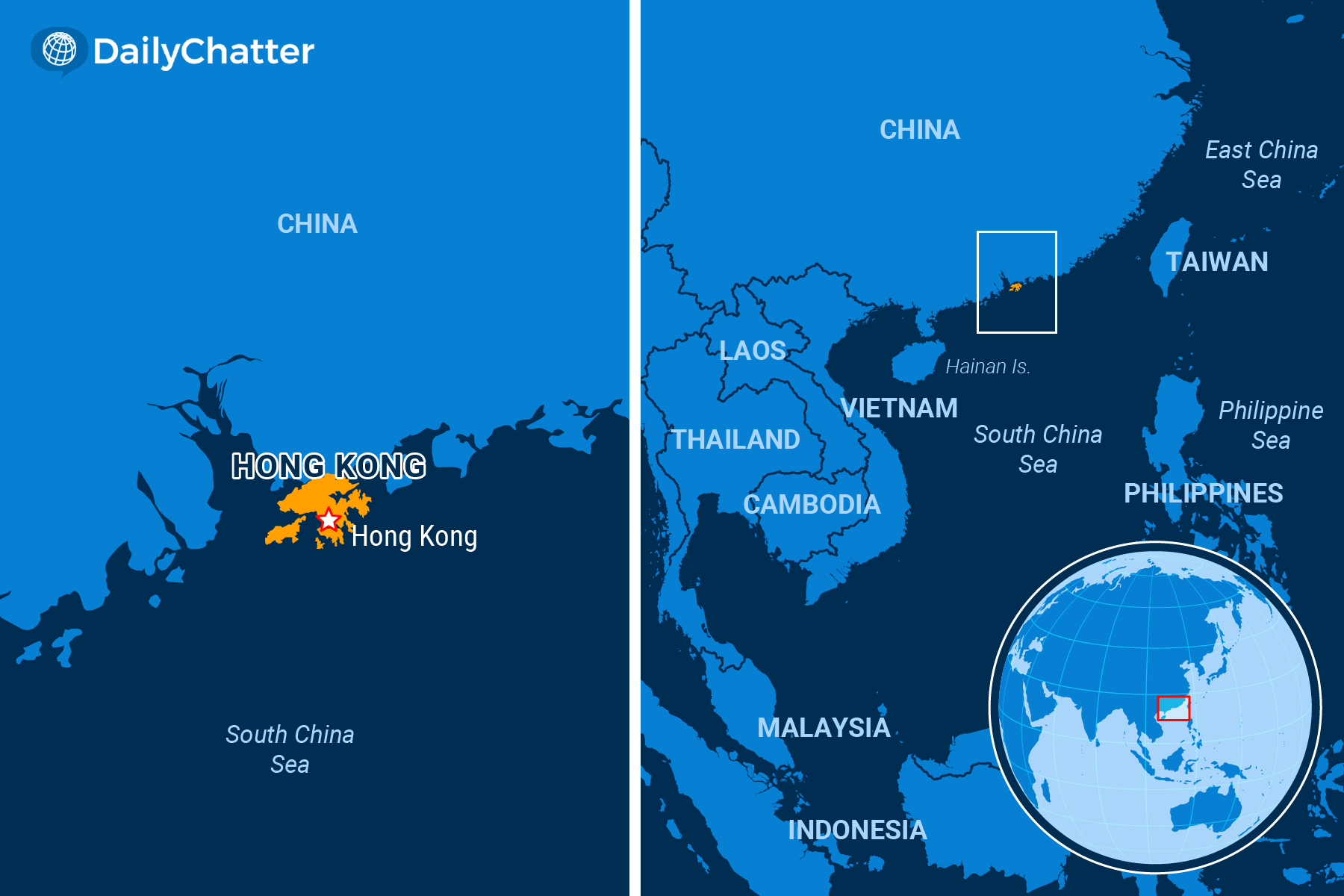

Bowing to pressure from mainland China, lawmakers in Hong Kong on Tuesday unanimously passed a new national security law, enabling the city’s government to crack down on dissent after decades of public resistance to Beijing, the New York Times reported.

The bill serves to enact Article 23 of Hong Kong’s Basic Law. It was passed quickly and will take effect on March 23. It targets five types of offenses: treason, insurrection, theft of state secrets, sabotage, and external interference. People found guilty of these offenses face penalties ranging from 20 years to life in prison.

Businesses, journalists, civil servants and academics are among the people most at risk, according to analysts. As a result, the new measure makes Hong Kong’s future as an international city doubtful.

A former British colony ceded to China in 1997, Hong Kong has long enjoyed more freedom than the mainland thanks to a state of partial autonomy that had attracted international workers and companies. Now, the new legislation brings the city a step closer to Beijing.

It has also shored up another national security law, passed in 2020 following months of anti-government protests in 2019. Under that law, opposition figures who criticized Article 23 were sent to jail.

Other critics went into exile. Ahead of Tuesday’s vote, the British government relaxed rules for Hong Kong residents to apply for a visa in the United Kingdom, Radio Free Asia reported. According to government figures from November 2023, at least 191,000 people have applied for the visa scheme.

Article 23’s rapid passage “is meant to show people in Hong Kong the government’s resolve and ability to enforce it,” Steve Tsang from the School of Oriental and African Studies in London told the New York Times.

Attempts to pass similar laws failed in 2003 after hundreds of thousands of Hong Kong residents took to the streets. For years, leaders feared backlash and refused to raise the matter again. But Hong Kong’s political climate has changed in the ensuing two decades, allowing Article 23’s passage, former lawmaker Emily Lau told the BBC.

The legislation only vaguely defines the offenses and could “take repression to the next level,” Amnesty International said. Its language mirrors security legislation effective in mainland China, the New York Times noted.

It could also make Hong Kong disadvantageous for international businesses. Executives said they would face costs to ensure companies comply with the new law.

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $32.95 for an annual subscription, or less than $3 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.