The War Dividend: In Sudan’s Civil War, a Gold Rush Precludes Peace

When war erupted in Sudan’s capital in April 2023, Zainab Aamer faced an impossible choice: stay and risk death, or flee into unknown danger.

Aamer, a widow and mother of six, had worked as a nurse in Khartoum before she decided to leave, becoming one of more than 12 million internal refugees in what the United Nations calls the world’s largest displacement crisis.

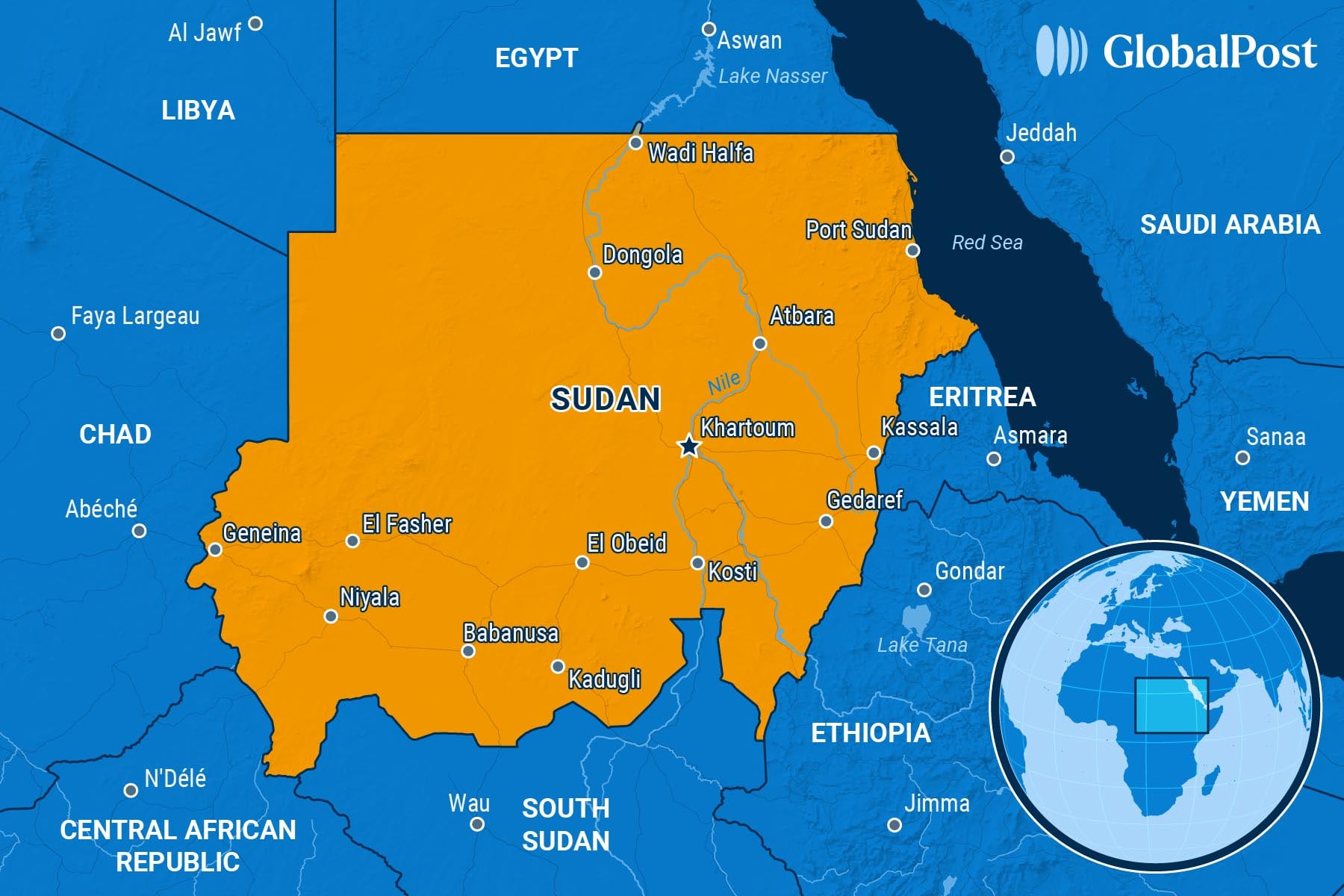

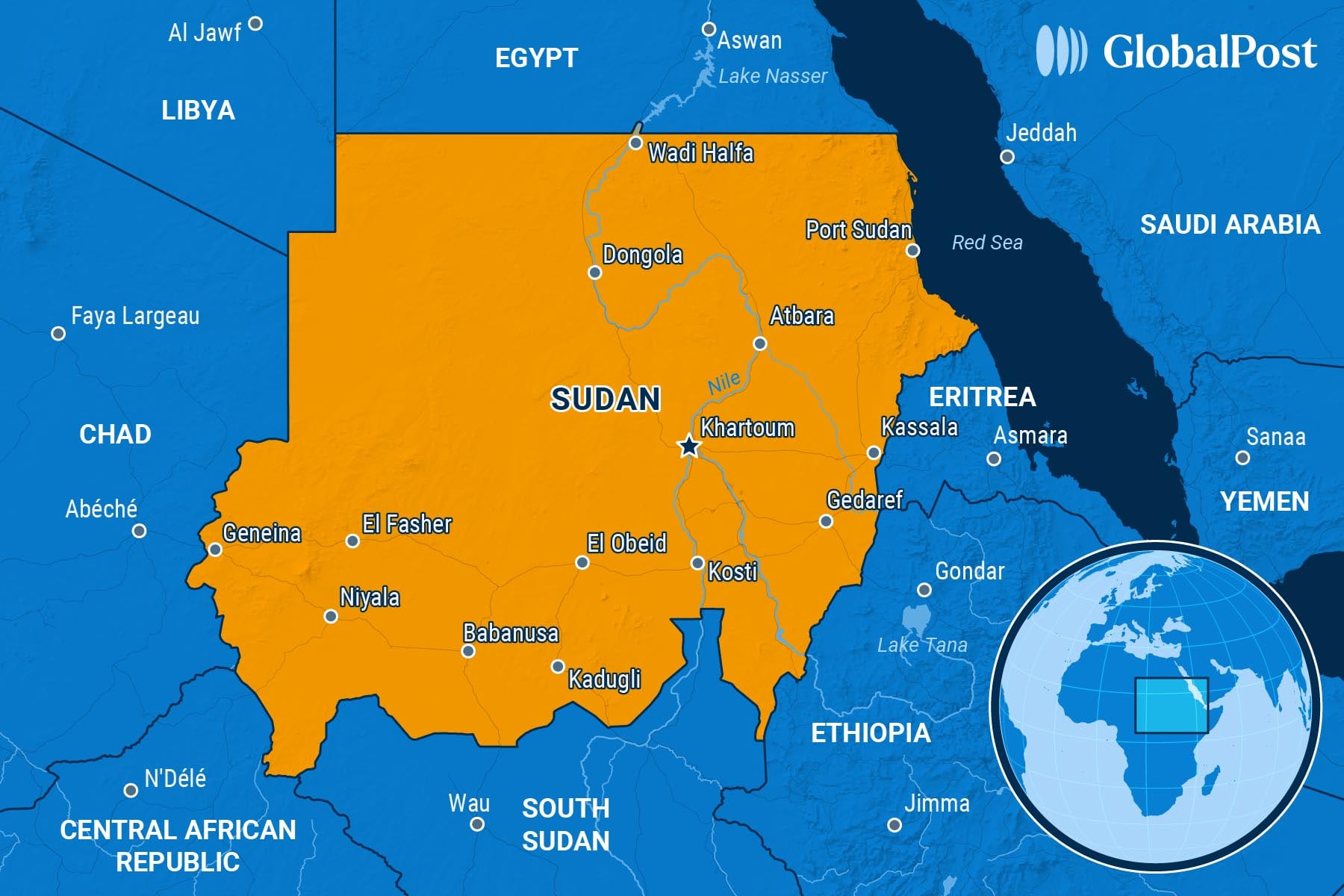

“I had to protect my daughters,” she said, recounting the perilous 500-mile journey to Port Sudan on the coast that cost her eldest son his life.

For the internally displaced like Aamer, the announcement in September by the group known as the “Quad” – the United States, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates – of a proposal for a three-month truce and a permanent peace should bring some hope for the future.

But it likely won’t, say analysts. That’s because this conflict is not just about power and territory and tribes – it’s about gold, which means it’s too lucrative a war for its key players to want peace.

“The gold trade connects Sudan’s civil war to the wider region and highlights the roles that commodities play in perpetuating violent conflict,” wrote the British think tank, Chatham House. “The multi-billion-dollar trade of gold sustains and shapes Sudan’s conflict. This commodity is the most significant source of income for the warring parties, feeding an associated cross-border network of actors including other armed groups, producers, traders, smugglers, and external governments.”

In 2019, Sudan saw a popular revolution that ousted longtime dictator Omar al-Bashir, who was in power for 30 years. Afterward, a transitional civilian council took over the country before being deposed by another military coup in 2021. Afterward, as protesters fought for a transition to democracy, power struggles grew between the army commander leading the country, Gen. Abdel Fattah al-Burhan of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), and his deputy, Muhammad Hamdan Dagalo (known as Hemedti), head of the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a militia that arose out of the Janjaweed terror group in the Darfur region that killed thousands of people there in the 1980s.

In April 2023, war broke out over the integration of the two forces. In the two years since, the fight has killed about 150,000 people.

Both sides have to date rejected moves toward peace. In August, Burhan said he would “defeat this rebellion.” Hemedti, who was sworn in as head of a parallel government in April, says he represents Sudan’s future with “a broad civilian coalition that represents the true face of Sudan.”

Meanwhile, they have carved up the country and its resources among themselves. The SAF controls the north, the east, the capital of Khartoum, and Sennar state in the south. The RSF controls parts of the south and center and most of the west of the country, where it is fighting for control of El-Fasher, its last stronghold in the resource-rich Darfur region. Elsewhere in the country, there are other rebel groups and tribal militias holding on to smaller fiefdoms, fighting one or both parties.

And both profit from, and are supported by, the production of gold, which is increasing in the country: Last year, Sudan’s state-owned Mineral Resources Company reported gold production hit 64 tons in 2024, up from 41.8 tons in 2022.

Along with the increase in production, the value of gold gained 27 percent in 2024, capping a decade in which it has more than doubled in value. In the first six months of this year, gold’s value increased by a further 24 percent.

Both the RSF and the SAF are not only deeply involved in the production of gold in the areas they control, but even work together to harvest the riches and smuggle them out of the country, said analysts. As a result, foreign powers have created “networks of dependency” through gold smuggling, with “Dubai already serving as the primary destination for gold smuggled by militias,” wrote Noria Research in a recent analysis. “Regional powers currently intervening in Sudan do view the country as the site for national interests, but in the manner that 19th-century colonial powers viewed Africa.”

And a weak Sudan, one in a state of civil war, makes stealing its resources far simpler, it added, because “a unified state cannot assert sovereignty to any meaningful degree… This is a much simpler task than navigating a constellation of bureaucrats, judges, businessmen, politicians, and civil society, as would be the case were Sudan made whole again.”

The UAE is the key foreign player in Sudan but far from the only one. The SAF has received weaponry and financial support from Russia’s Africa Corps (formerly the Wagner Group of mercenaries), Turkey, Iran, Egypt, and Qatar, among others. The RSF has received support from the UAE and those it has influence over, including Kenya, Uganda, Libya – via Khalifa Haftar – and Ethiopia.

As a result, analysts say what has developed in the region is a broader regional gold economy with a constellation of war-torn countries such as Libya, the Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of Congo revolving around the UAE: Almost half of all exported African gold flows there, where its origins are scrubbed before being sold.

For the UAE, it’s not just about the riches, but about power in the region, food security, and a return on its investment, say analysts.

“The UAE has emerged as the foreign player most invested in the war,” wrote May Darwich of the University of Birmingham, in the Conversation, noting the country’s more than $6 billion in investment into Sudan. “It views resource-rich, strategically located Sudan as an opportunity to expand its influence and control in the Middle East and east Africa.”

The UAE also recruits mercenaries from Sudan, for example, for its fight in Yemen.

Emirati officials have repeatedly denied the UAE’s involvement in Sudan, claiming its neutrality. But US officials have blasted the country for its involvement in the war and for sustaining the conflict.

Meanwhile, as gold continues to flow out of Sudan, its warring parties have yet to respond to the proposal by the Quad.

That means more waiting for the dividends of peace for children like Sondos, 8, who, with her family, fled to yet another refugee camp because of repeated RSF attacks on El-Fasher, the capital of Sudan’s North Darfur state, and its refugee camps of Zamzam and Abu Shouk. Famine is growing in the region due to a blockade by the militia, the UN says.

We had no choice but to leave, Sondos says: “There was only hunger and bombs.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $46 for an annual subscription, or less than $4 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.