Dreams of Destiny

Late last year, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan said that Turkey needs breathing room.

“Turkey is much bigger than Turkey,” he said during a speech in December. “As a nation, we cannot limit our horizon to 782,000 square kilometers … or hide from this destiny … Those who ask, ‘What is Turkey doing in Libya, Syria, and Somalia’ may not be able to conceive this mission and vision.”

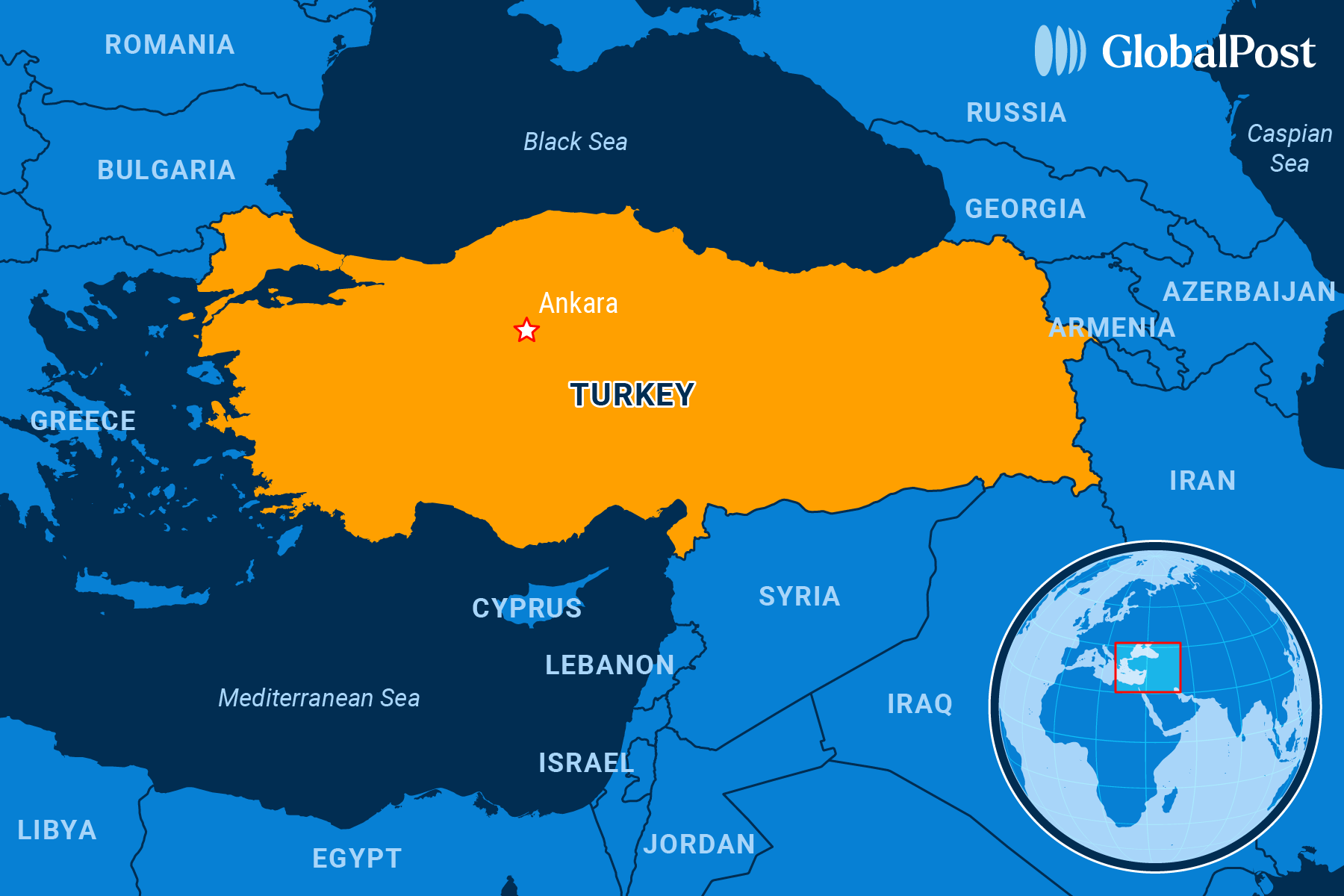

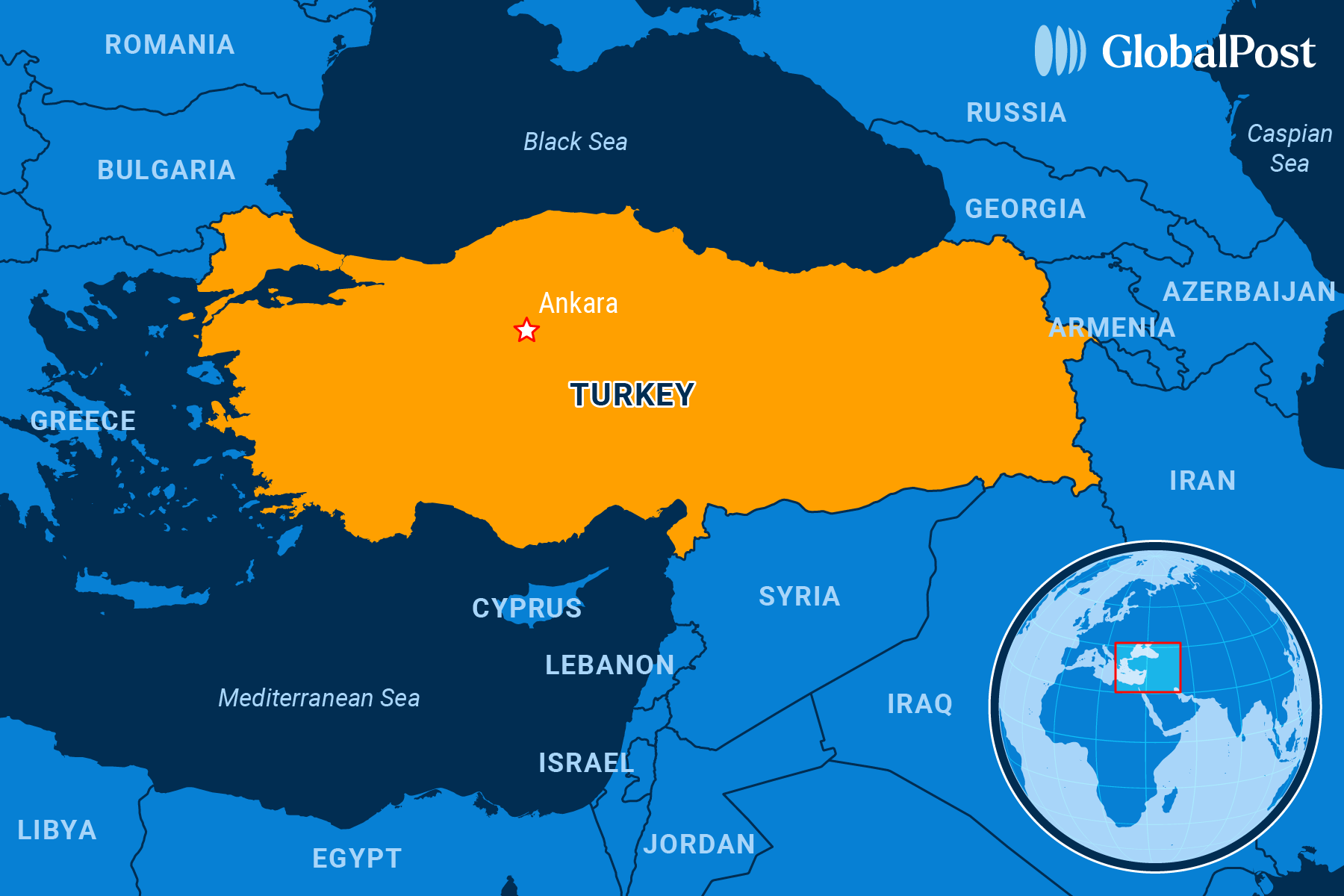

Such sentiments are making Arabs, Israelis, Europeans, and others nervous. For years, Turkey’s involvements in the Middle East, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas have drawn criticism that Erdoğan is looking to resurrect the Ottoman Empire, which controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia and North Africa from the 14th to the early 20th century.

“There’s some people in Turkey … (who) believe that they could recreate the Ottoman Empire, including parts of Greece, parts of Syria, parts of Iraq, parts of Iran, half of the Caucasus, etc.,” Greek Defense Minister Nikos Dendias told Fox News. “I hope that this is a daydream.”

While Greece has long had a strained relationship with Turkey, some in the Middle East have been worried for years about Turkey’s “neo-imperialist, neo-Ottoman” approach to expansion, which Erdoğan calls the “Turkish Century.” Now, with its strong influence over its southern neighbor Syria, which deposed its longtime tyrant Bashar Assad in December, this issue is coming to a head.

Turkey has been involved in Syria for years, bankrolling the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) group that is now in control of the country, and also other rebel groups, including the Syrian National Army (SNA). In parts of northern Syria, including Idlib, the stronghold of the HTS, it’s more Turkish than Syrian: Stores display Turkish products, which are paid for in Turkish lira. Schools, clinics, and electricity are provided by Turkey. Mobile phones use Turkish SIM cards.

Since the new Syrian government came to power, Turkish officials became the first foreign delegation to make official visits and have offered to advise it on governance issues and a new constitution. Turkish businessmen are eyeing opportunities in Syria for expansion. The country has also offered to train and equip Syria’s new army. Last week, Syria and Turkey discussed a new defense pact that could see Turkish bases on Syrian soil.

One tricky issue, however, is the Kurds. The US allied with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) a decade ago to fight the terrorist Islamic State group. However, Turkey sees the Kurds as its enemy and has attacked and forced their retreat, occupying parts of their territory in northern Syria.

“Turkey wants to smother Kurdish autonomy in Syria’s north, help build a new Syrian army, and regain influence in a country it once controlled for 400 years,” wrote the Economist.

Now Turkey wants the Kurds’ militias, including the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), both of which it views as “terrorists”, to disarm. The leader of Syria, Ahmed al-Sharaa of the HTS, wants to integrate all Kurdish units into Syria’s new army along with the SNA. The US, meanwhile, wants to protect its allies in the SDF – and thousands of US troops who work with them, and allow them to continue to fight Islamic State. The Kurds, meanwhile, want autonomy.

Meanwhile, Turkey, a majority Sunni Muslim nation, has long had a rivalry with the other powerful Sunni nations in the region, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates, for influence over the Arab world. Now pleased that Syria has broken free from the Iranian dominance under the Assads, these players don’t want Iran replaced by Turkey.

At the same time, Israel is nervous that Turkey may gain access to Syrian airspace and deploy air defenses or other weapons there because it could extend Turkey’s influence to the Golan Heights and even Lebanon, helping Hamas: “Turkey is already one of the most hostile countries to Israel – in public statements and its backing of Hamas,” wrote the Jerusalem Post.

Turkey, meanwhile, fears Israeli expansionism, seeing it as a threat to its security, wrote the Daily Sabah, a Turkish newspaper.

Analysts say a number of countries are nervous because they have seen Turkey try to increase its control over the Mediterranean as part of its “Blue Homeland Doctrine,” for example, in its controversial mineral deal with Libya a few years ago, which caused issues in NATO – Turkey is a member as is Greece. They also point to Turkish meddling in the Armenian-Azerbaijan conflict.

The Horn of Africa and the Red Sea are another combined source of contention, especially for Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, all of whom consider the region in their sphere of influence and covet its mineral riches and strategic position, as well as its development potential.

Turkey has been expanding its influence there over the years, signing defense and economic cooperation agreements with Ethiopia, Djibouti, and especially Somalia, where it is deeply integrated into the economy and its military and where it has a military base. It’s played mediator between Ethiopia and Somalia and supported the government of Sudan in its civil war. More than 30 African states have security cooperation agreements with Turkey.

Still, it’s Turkey’s move to make peace with the Kurds after decades of conflict that could allow Turkey to achieve its “destiny,” say analysts.

Since last year, Turkey has been in peace talks with the PKK’s leader, Abdullah Öcalan, who has been in jail for decades. Turkey wants Öcalan to renounce violence, which he may do this month. If he does, Turkey may end its four-decade war on the Kurds and integrate the Kurds into Turkey’s constitution, governance, and society. It will also, Turkey hopes, neutralize them in Syria, where they control one-third of the country and most of the oil fields. In Iraq, it hopes it will sideline the elements of the PKK there – Turkey already has a good relationship with the Kurdish leaders of Iraqi Kurdistan. Meanwhile, it will undercut Israel’s outreach to Kurds and unify Turkey and Erdoğan’s hold over it.

The biggest obstacle to this plan – and Turkey’s expansion over Kurdish regions outside of its borders – is the United States, wrote Foreign Affairs. But in spite of a push by US officials to maintain its relationship with its Kurdish allies in Syria, the magazine notes that President Donald Trump has been vague about maintaining the 2,000 US troops there, saying recently, “They don’t need us involved.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $46 for an annual subscription, or less than $4 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.