When the Walls Close In: Multiple Crises Create Mass Displacement in Cameroon

In April, a Cameroonian national living in the US state of Maryland was indicted by federal prosecutors who said he had been “conspiring to provide material support to armed separatist fighters… in Cameroon…”

Eric Tataw, 38, had allegedly ordered the “murder, kidnapping, maiming of civilians” as well as raised funds for armed groups in Cameroon, the indictment said.

Since 2016, the violent conflict in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions, the North West and the South West, has killed at least 6,000 people.

Here, separatist armed groups have committed serious human rights abuses such as mutilation and torture, according to Human Rights Watch. But so have Cameroonian government forces, carrying out mass killings, the torture of civilians, and the widespread burning of homes. Perpetrators have faced little accountability, the organization added.

Caught in the middle are the more than 334,000 people forced from their homes, which, along with other civilians fleeing conflict elsewhere, make Cameroon host to one of the world’s worst and most neglected refugee crises, according to a new report by the Norwegian Refugee Council. The country hosts 1.5 million people forced from their homes by violence.

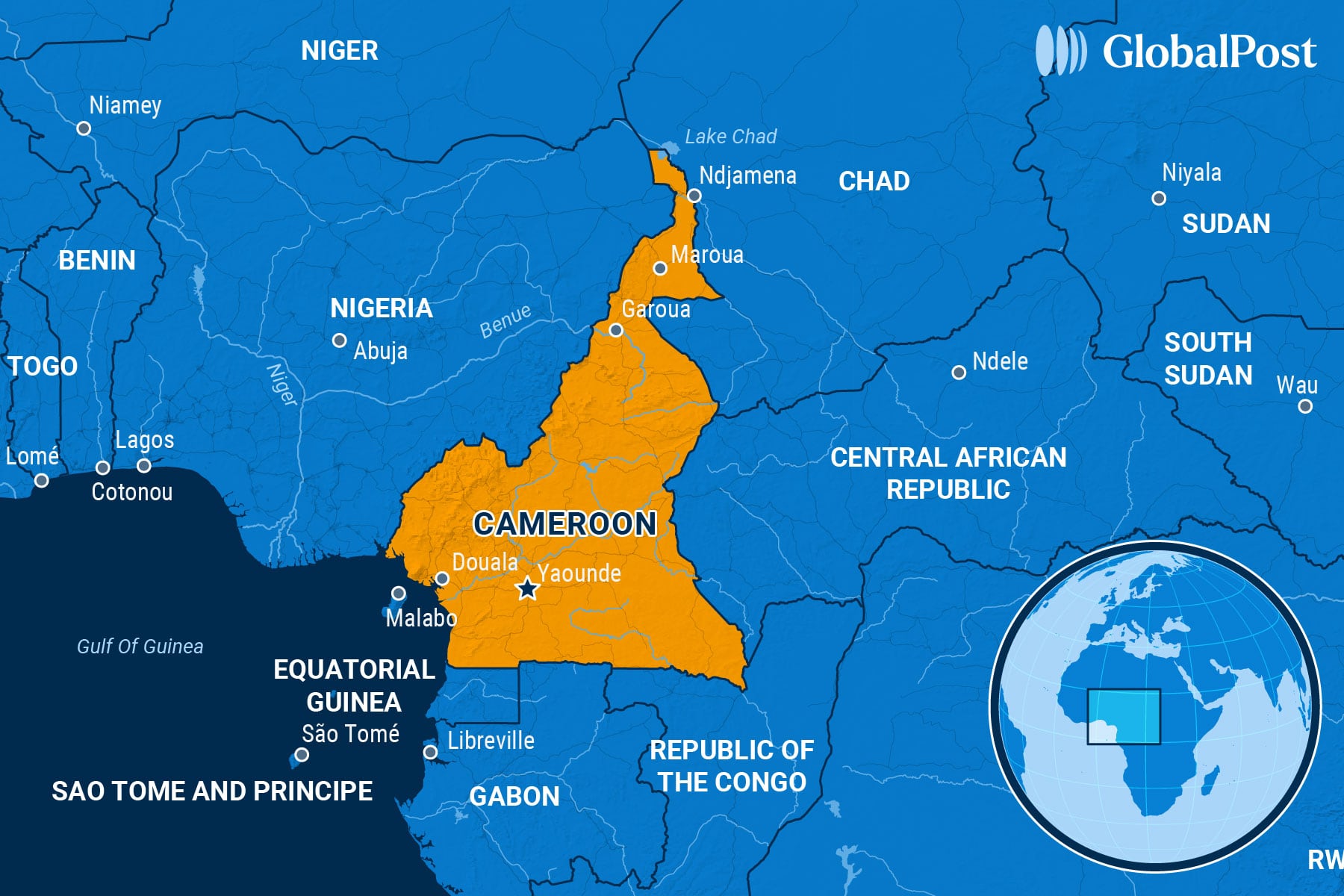

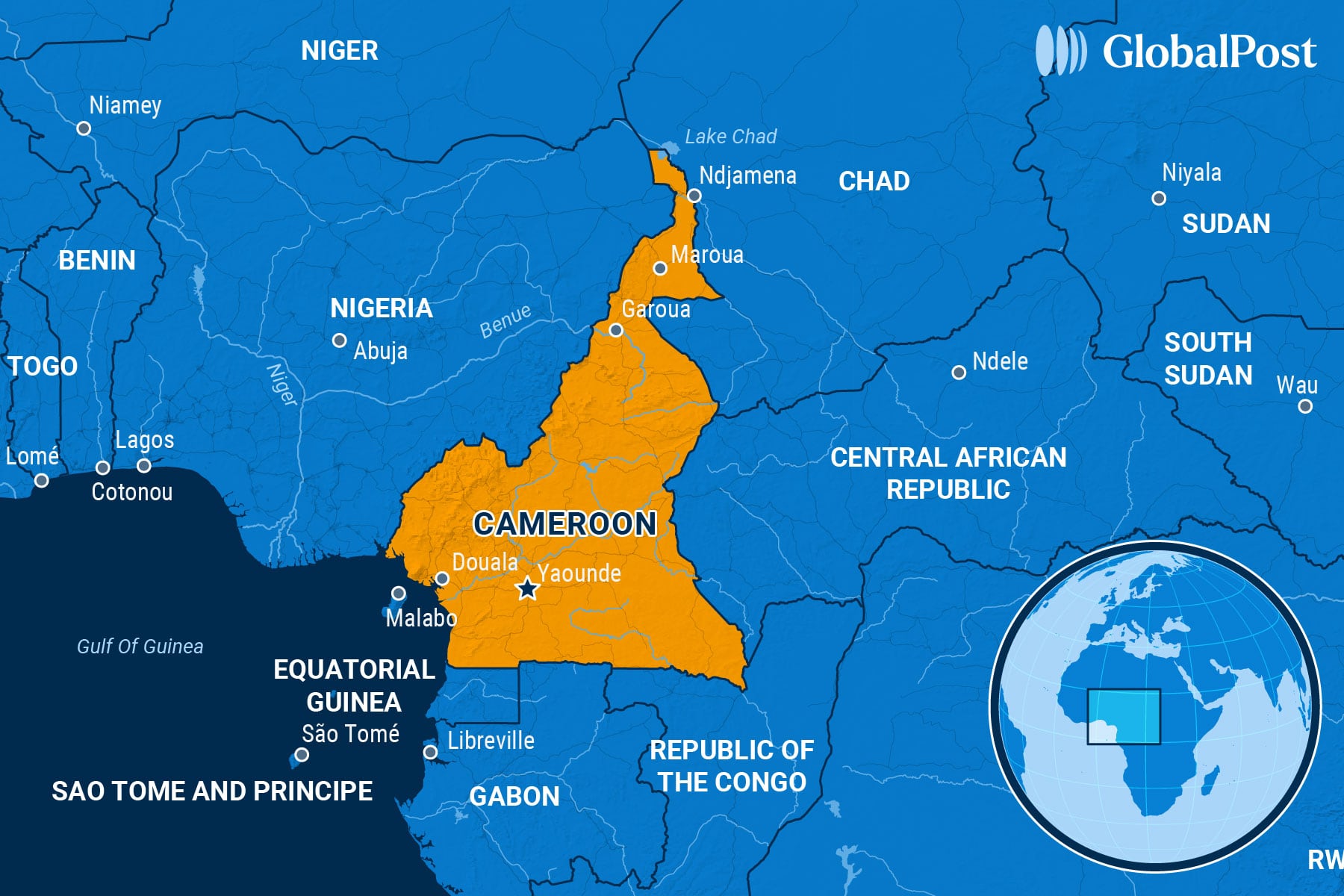

The problem is that the country has been hit by multiple crises simultaneously – terrorists and criminal gangs in the north, a civil war in neighboring Central African Republic, and the almost-decade-long fight between separatists in the English-speaking regions and the government of the French-speaking majority.

Anglophone Cameroonians make up around 20 percent of the country’s 28 million people.

The crisis in the English-speaking regions, which were governed by the United Kingdom after World War I until independence in 1960, with France governing the rest, broke out after teachers and lawyers in them began protesting the imposition of French within the Anglophone education and judicial system in 2016.

The situation escalated after the government cracked down on the protesters, with a separatist movement emerging that wanted to secede from Cameroon into a new state called Ambazonia.

“The fight for homeland is existential and non-negotiable,” Sisiku Julius Ayuk Tabe, the former “president” of the breakaway state that is still fighting his revolution from jail after seven years in prison, told the Guardian. “We have an obligation – dead or alive – to bequeath to our children a nation that they can call theirs, something we have been deprived of for too long.”

More recently, the conflict in the Lake Chad region, which also includes Cameroon’s far north Logone-et-Chari district, has been heating up as Islamist militants intensify their cross-border operations and criminal networks continue to operate freely.

Much of the violence is due to the Nigerian militant group Boko Haram which split into two factions: The Islamic State West Africa Province, has tried to push “a kind of heart-and-mind-winning strategy,” trying to set up state-like structures in occupied areas and “sometimes trying to deliver social services, but most of the time preying on communities in terms of extortion and illegal tax collection,” Remadji Hoinathy of the Institute for Security Studies told Deutsche Welle.

The second faction is People Committed to the Prophet’s Teachings for Propagation and Jihad (JAS), which employs indiscriminate violence against the military, local authorities, and civilians – locals are often forced to pay taxes or collaborate with the groups.

In March 2025 alone, there were more than 10 surprise attacks on military barracks in which the perpetrators stole military equipment, weapons, and cars.

As a result of the violence, hundreds of thousands have fled the area.

Adding to that are the 430,000 refugees who have fled conflicts in the central African region, the majority from the Central African Republic.

Constance Banda, who with her husband and six children fled the violence in the English-speaking regions, now lives in a makeshift refugee camp in the capital of Yaoundé.

“It’s very hard for us here,” she told Radio France International. “My children sometimes go for days without food. All I pray for is for the fighting to end so that we can return a rebuild our lives.”

Subscribe today and GlobalPost will be in your inbox the next weekday morning

Join us today and pay only $46 for an annual subscription, or less than $4 a month for our unique insights into crucial developments on the world stage. It’s by far the best investment you can make to expand your knowledge of the world.

And you get a free two-week trial with no obligation to continue.